by Mike Higgins

For a few brief days cruising frees me from bills to pay, garbage to take out, and e-mails to answer. It clears my schedule and refills it with tasks chosen, based on the more real needs of staying afloat, getting from here to there, and keeping warm and dry. Cruising does involve work. Indeed sailing itself can be a full-time job. There is often so much to do that I can go an entire day without even thinking about eating. But eat I must, and for me that usually involves cooking. Making my own meal in a secluded anchorage at the end of a long day’s sail completes the sense of freedom that comes with small boat cruising.

The Challenge

Like most small cruisers, my boat lacks the cabin space needed for a proper galley. Therefore, I cook alfresco in my cockpit and enjoy the scenery, which usually is why I am there in the first place. This article describes how to build the portable galley or cook box I use on my boat.

The top lid opens up to expose the stove and create a working area. The metal top surrounding the burner provides a heat resistant surface for hot pots and pans. Side doors fold down to expose storage for cooking equipment and supplies. Mostly I cruise alone so everything can be reduced in size. The burner is a standard backpacking stove, fueled by compressed gas canisters. Most of the utensils were bought from the same store that supplied the stove.

Fitting the Problem

Readers are encouraged to adapt my design to their own requirements. For example, the lid on mine cries out for a carrying handle. I omitted this obvious convenience because there is not enough vertical clearance in the cabin space where I store my box. Instead I make do with the folding handles on either end. Adapting the design to personal requirements begins by determining available storage space. My cook box fits easily in a space 18 inches deep and 10 inches square.

Selecting a Stove

I own a classic brass Svea stove, based on a design that goes back to the late nineteenth century. As a traditionalist I was tempted by the simplicity and reliability of this elegant design. However, the dangers of liquid fuel on a wooden boat influenced me to choose a Primus Yellowstone Classic Trail Stove with an easily available 3.53 ounce isobutane-propane canister. Readers less squeamish about liquid fuel might consider the Coleman Exponent Feather 442 Dual Fuel Backpacking Stove. This compact alternative uses either white or unleaded gas and has roughly the same dimensions as the Primus.

The drawing in Figure 2 shows how the height of the stove affects the dimensions of the cook box (note that the stove shown in this drawing only approximates the appearance of the Primus). The rest of the box must position the metal surface level with the burner itself. This creates a very stable platform for pots and pans.

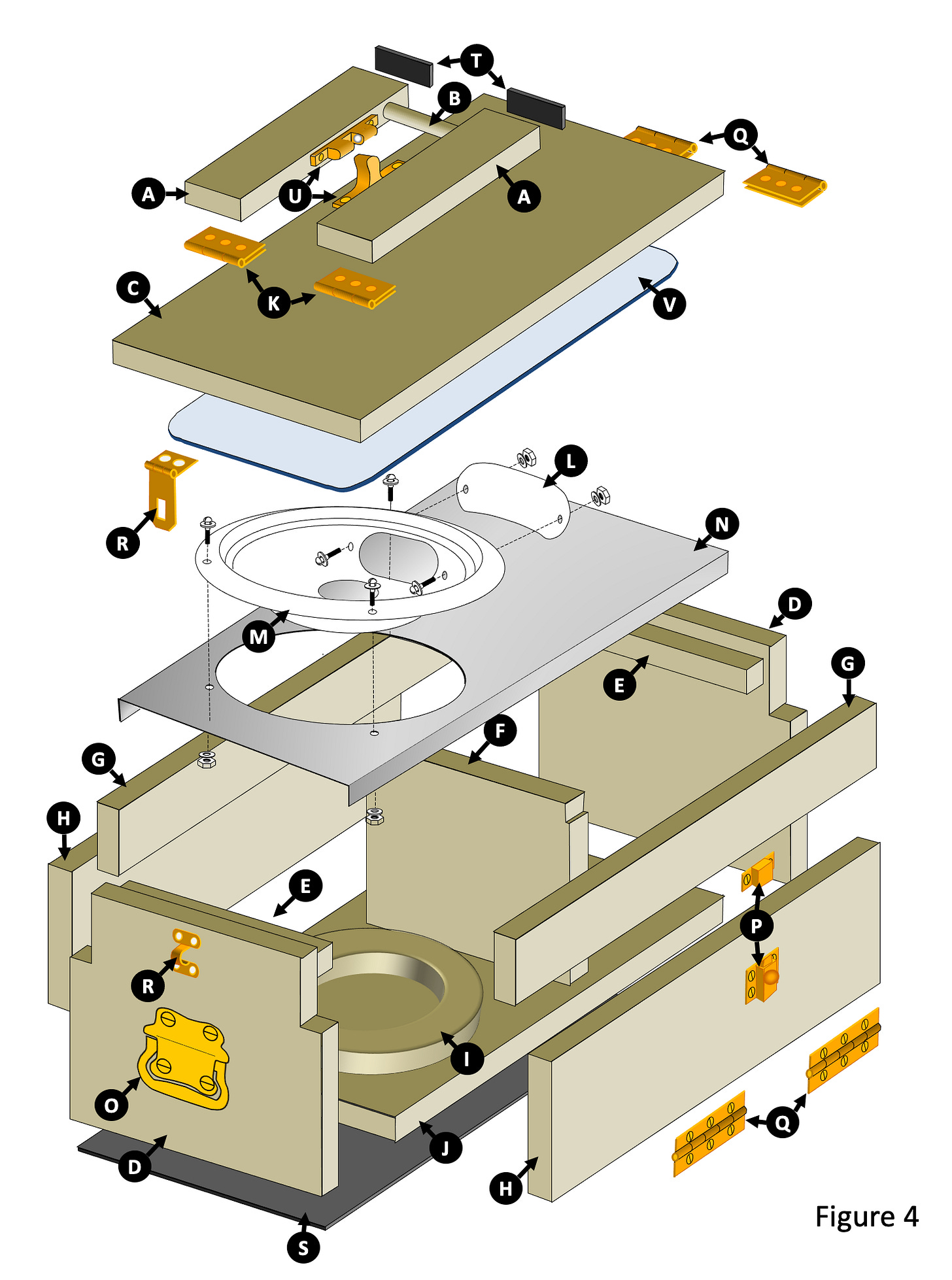

Figure 2 also shows two design features critical to safety. Building a cooking appliance out of wood is an iffy proposition. Wood must be shielded from high temperatures. This includes radiated heat as well as the actual flame itself. My design shields the wood with a generic burner drip pan purchased from a hardware store. Figure 4 shows how the drip pan is combined with the sheet metal top. Note also the metal patch that covers the electrode opening in the drip pan and prevents heat from the stove charring the wooden interior of the box.

The other safety feature shown in Figure 2 is the wooden annulus that holds the stove in place—also shown in Figure 4 (Part I). The inside diameter of the annulus is slightly larger than the outside diameter of the fuel canister (or stove base if a liquid fuel stove is used). The result is a secure and stable platform. An empty canister is replaced by unscrewing the burner mechanism and lifting the canister out of the annulus and through the side door.

Undoubtedly, readers using the Primus stove will carry a spare canister; however, storing that spare in the cook box is not advised. In the unlikely event that the cook box catches fire, an extra canister in close proximity could make a bad situation far worse.

Built-in Storage

The compartment opposite the stove in Figure 2 stores the cooking pots and other utensils. Something like the MSR Alpine 2 Pot Set is a good choice. This set includes two pots, a lid that doubles as a dish, and a lifting handle. Additional utensils, like lighters and dish cloths can be stored inside this compact setup. The storage compartment in my cook box also has enough room for a Tupperware Sandwich Keeper that organizes odds-and-ends. I added racks to the inside of the doors for holding various implements and small bottles of spices. Along with the stove, it is a good idea to buy all of the major pots and utensils before starting the project to make certain that everything will fit.

Overall Construction

Figure 3 shows the overall appearance of the finished cook box. The exploded view in Figure 4 shows how the components fit together. The list of materials at the end of the article includes parts dimensions.

Readers can choose their own materials and construction method. I used simple screwed-and-glued joints and quarter sawn clear Douglas fir. Gorilla Glue is a popular adhesive these days because it holds well even if the fit of the joint is not tight. I prefer to spend more time on the joints and use epoxy or one of the new advanced proprietary polymers like Titebond III. These strong waterproof adhesives avoid the messy squeeze-out that gives Gorilla Glue its gap-filling properties.

I also used expensive bronze flathead screws. Saving money on fasteners for a small project like this is a false economy. Brass screws tend to break and steel will rust no matter how hard you try to keep your cook box away from water. A few years ago my cook box found itself immersed in saltwater over night after an unplanned encounter with a submerged piling. The bronze fasteners survived that ordeal with only a slight patina of copper oxide.

Metal Part Assembly

I recommend starting with the sheet metal parts (Parts L, M, and N). Ideally the top (Part N) would be made from stainless steel since this durable metal has much lower thermal conductivity when compared to aluminum. On the other hand, aluminum is easier to cut and bend. Readers with better sheet metal working skills than I might choose stainless steel instead.

For me, metal bending is an inexact process with unpredictable results. Forming the metal top and then cutting the wood to size can cover up mistakes made while bending the flanges. The dimensions given for the sheet metal top (Part N) include the 1 inch required for the pair of ½ inch flanges formed along the two long sides. The other dimensions in the design assume that the outside width of the top, after bending the two flanges, is 7 ¾ inches.

Cutting the hole can be one of the more dangerous steps in the project. Assuming the use of a circle cutter (also known as a trepanning cutter), be sure to clamp the aluminum securely to the drill press table. A spinning piece of sheet metal can end the project prematurely. A tin snip artist also could achieve satisfactory results since the edge of the hole will be hidden by the drip pan flange (Part M). I assembled the sheet metal pieces using small-diameter brass nuts and bolts with large washers.

I used a wasteful trick to make the patch (Part L) that covers the electrode hole in the drip pan (Part M). Since the drip pans were relatively inexpensive, I bought two and cut up one to make the patch. The result was a patch that perfectly matched the curvature of the drip pan and a large piece of scrap for my recycling bin.

Glued Wooden Parts

The ends (Part D) and side rails (Part G) can be cut out once the metal top is finished. Assuming that ¾ inch stock is used for these pieces, the width of the ends should be 1½ inches more than the outside width of the metal top. Similarly, the length of the side rails should be 1½ inches more than the length of the top. After cutting the notches in the upper corners of the end pieces, the four parts can be temporarily assembled with screws to check for fit with the metal top. Assuming that everything fits, the bottom piece (Part J) can now be made. Temporarily attach it to the end pieces with screws.

The next step is to attach the metal top. This requires cutting the support pieces (Part E) that attach to the ends. Notice that these support pieces must fit between the flanges on the metal top. Therefore, the lengths of the support pieces should be approximately ¼ inch shorter than the outside width of the metal top. In my cook box I placed the support pieces ½ inch below the top edge of the ends. This provides clearance between the metal assembly and the lid. The position of the support pieces also determines the height of the metal surface, relative to the top of the burner. Therefore, the stove should be installed and its height compared with the location of the metal top. The support pieces must be held in place temporarily during this procedure. Proper sized C-clamps are useful during this step. Once the location for the support pieces is determined, they should be temporarily attached to the ends with screws.

Now is a good time to cut and position the annulus (Part I). Of course, it really doesn’t need to be an annulus. Three or four properly positioned blocks will work just as well. However, the structure used to secure the stove should be fitted and temporarily attached to the bottom at this time. Make sure that the burner is aligned with the center of the opening in the metal top.

The separator between the two compartments (Part F) can now be fitted. The width of this piece matches the inside distance between the two side rails (Part G). The top of the separator should align with the two supports (Part E) attached to the ends (Part D). Note also that small notches must be made in the top corners of the separator to allow for the ½ inch flanges on the metal top. If the reader is a slave to symmetry, the separator will be installed midway between the two ends. Alternatively, the separator can be moved as close as possible to the stove in order to maximize the storage space available in the adjacent compartment.

The pieces cut so far (Parts E, D, F, G, I and J) can now be glued together. Disassemble everything after marking the location of each part. This is a good time to sand all of the pieces. Then start by gluing and screwing the smaller pieces together. For example, fasten the supports (Part E) to the ends (Part D) and the annulus (Part I) to the bottom (Part J). Next attach the side rails to the ends. Finally, install the bottom (Part J) and the separator (Part F). Notice that the glue joints between the ends and the bottom involve end grain and will not be strong. The same is true for the joint between the separator and the bottom. Therefore, the strength of these joints mostly depends on the screws. Before the glue has set, be sure that the metal assembly still fits. Also wipe away the excess glue that should have squeezed out from the joints.

Fitting the Side Doors and Top Lid

Care should be used when selecting the wood used for the top lid and the side doors. These parts are not stabilized by glue joints with other pieces in the cook box. Therefore, warping will be a problem unless the wood is straight-grained and thoroughly dried. If available, the reader might consider using high quality marine grade plywood for these parts.

The side doors are cut to fit the space between the bottom (Part J) and the side rails (Part G); however, keep in mind that wood will swell slightly in a marine environment. Therefore, it should be a loose fit. Also, the top edges of the doors require a chamfer in order to clear the underside of the side rails. Racks planned for the inside of the doors should be added at this time. Make certain that the racks do not interfere with the separator (Part F) or annulus (Part I) when the doors are closed.

The top lid (Part C) is cut to fit the outside dimensions of the box. A piece of hard plastic countertop material (Part V) is then glued to the underside of the top lid. This creates a cleanable food preparation surface when opened. The dimensions shown in the list of materials assume that the counter top material will be inlaid into the top lid with 2 inch margins on the ends and 1 inch margins on the sides. A less ambitious approach would cover the entire bottom surface of the top, leaving space for the hinges (Part Q) and the hasp (Part R). Folding legs (Part A) support the top when opened. The length of these legs equals the height of the cook box minus the thickness of the top.

Hardware

Using bronze hardware would be consistent with the recommended choice of fasteners. However, good bronze hinges and latches are hard to find at a reasonable price. Brass hardware is almost as durable and far more available. Be sure that the hardware is solid brass rather than “brass finished”. The latter will dissolve after a few seasons onboard a boat.

Readers who like woodworking may want to countersink the hinges. My side door latches are a little fancier than they need to be. These are solid brass cupboard catches purchased from a good chandlery. A simple pivoting toggle would work just as well and cost far less. I used a brass hasp to hold the top lid closed. The drawings do not show the tethered snap hook that secures the hasp. Don’t forget the cabinet catch (Part U) that keeps the folded legs in place.

Finishing and Other Details

I used a round-over router bit to remove the sharp edges from the exposed corners. Rounded edges are less prone to damage and less likely to mar the interior of your boat or scratch your sunburned skin. The radius of the router bit depends on the location of the screws holding the ends and sides together. I used a ½ inch radius bit on the top edges. The position of the screws limited me to a ¼ inch radius bit on the side edges.

Finally, rubber nonskid material is glued to the bottom of the cook box and the ends of the legs to protect the cockpit surfaces and minimize sliding. Good contact cement should be used as the adhesive.

I finished my cook box by oiling the wood surfaces because of concern that heat might damage paint or varnish. The nonskid material should be attached before applying an oil finish since contact cement adheres poorly to an oiled surface. Readers choosing to paint or varnish the wood can attach the nonskid material afterwards.

Epilogue

Late one winter afternoon, a few weeks before I began writing this article, I ran aground during an ebb tide. It was one of those silly mistakes that left me stuck in the mud a few hours before slack. This meant that I was not moving for several hours. After setting my anchor and calling home to report that I would miss dinner, I found myself with nothing to do but watch the water follow the moon out from under my keel.

On the other hand, it wasn’t a bad place to be. The weather was dry and warm for this time of year. The stillness at dusk is beautiful in the south end of San Francisco Bay where I was sailing. And then I remembered my cook box and the emergency can of stew I keep below in a locker. It wasn’t the same as the home-cooked meal I was missing. Still that warmed stew tasted awfully good as I watched the sunset and waited for the tide. •SCA•

Mike Higgins grew up in Seattle but now lives in the San Francisco Bay Area where he builds and sails boats named after his wife and daughter. When not messing around with boats he works in the medical device industry as an engineering manager.

First appeared in issue #71

I built this stove when this article first appeared. I still have it but no longer have the boat. Still, it would work not only for the boat but also for any camping situation. I still get a ton of comments on it. Thanks for designing it in the first place.

Mike, outstanding article. Thanks for taking the time to produce it so thoroughly . Of course, from you I would have expected nothing less.

Simeon & SCAMP Noddy