This is Not a Vacation

My wife was right. I had planned a small expedition and masqueraded it as a vacation. Now, four days into the trip, 43 nautical miles southeast of Pic River, Sarah was emotionally wrought.

By Matt Magolan

“You tricked me into an expedition,” my wife Sarah said, with large full tears welling up in her eyes, her voice rising in pitch as it always does when she’s upset with me.

“I guess I didn’t think this trip would be this hard,” I answered, shrugging my shoulders in lame defense. I’d spent a few years as a professional sailor; racing, cruising, making deliveries and rigging boats. All those were keel boats, usually large ones, so when I set out to plan an open-boat trip with our newly acquired 1983 Spindrift Daysailer, I might truly have been a touch naïve. I like to think I was ambitious. Unfortunately for my wife, who had said, “I’ve got enough stress in my life with work and family expectations. What I need is a vacation,” maybe I was too ambitious.

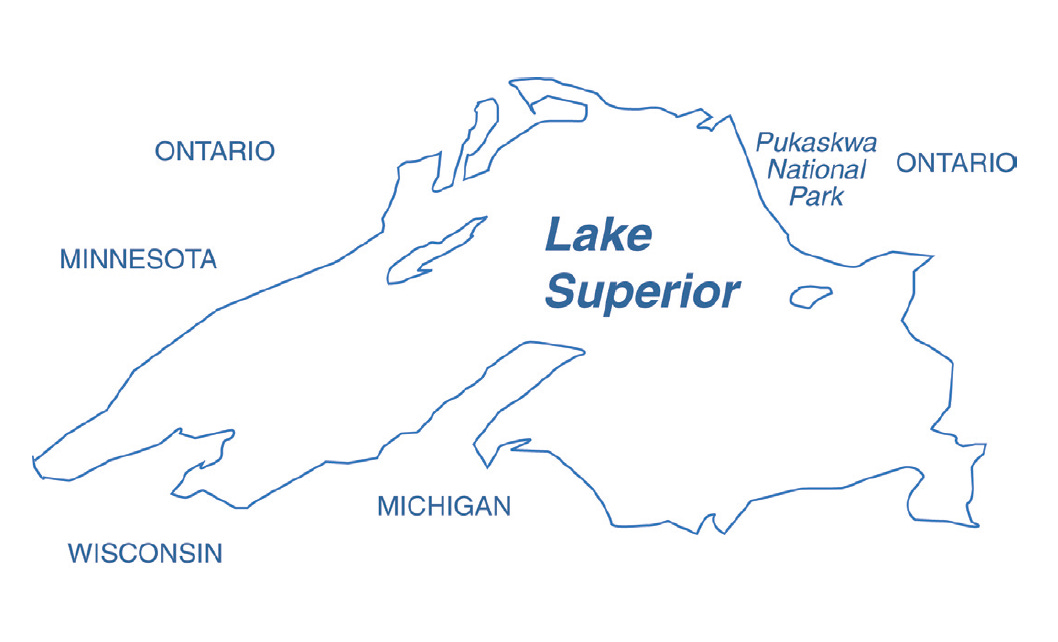

I’ve also spent a good part of my life as a professional sea kayaker and guide; so I see small sailboats as a natural fit for exploring the craggy secluded shorelines of the world. Pukaskwa National Park on the Ontario shore of Lake Superior is one such rocky coast. Pukaskwa is, without doubt, the most secluded and exposed shoreline on the Great Lakes. When near Otter Island, you are approximately 40 nautical miles from both Hattie Cove to the northwest and Michipicoten Harbor to the east. Over land, you’re approximately 40 nautical miles from Highway 17 through some of the densest forest in North America. In short, you’re at least 40 nautical miles from anything resembling civilization.

My wife was right. I had planned a small expedition and masqueraded it as a vacation. Now, four days into the trip, 43 nautical miles southeast of Pic River, Sarah was emotionally wrought. We were beyond the “point of no return,” and the Environment Canada weather forecast over our handheld VHF was dire. Both Sarah and I had serious concerns about our ability to make it to Michipicoten Harbor in the eight days we had set aside for the trip. Since the prevailing winds on this coast are W-NW I arranged for Naturally Superior Adventures staff to shuttle my Land Cruiser and trailer back to the Michipicoten River in Wawa from our put-in at Pic River. The plan was that we would sail the entire 90 nautical mile coast of Pukaskwa National Park and the Superior Highlands southeast of Pukaskwa.

The wind was 25 knots on the nose as we sailed S-SE down the Pukaskwa coast and the Spindrift was becoming difficult to handle as the seas rose to three-foot whitecaps. I had sewn a set of reef points into the original mainsail that came with the boat prior to the trip, but my measurements were off, so the reef didn’t flatten the sail as well as it should have. We had tested the reef in 15 knots back on Lake Waubesa near home, but 15 knots seemed like a zephyr compared to the 25 we now faced.

I’d scoffed when a local sailmaker had quoted me $100 for the reefs. In retrospect, that might have been a bargain. Instead, I bought a sewing machine off craigslist for $20, took some Dimension-Polyant sailcloth lying around my workshop and made my own reef points. It wasn’t my most successful project. Luckily, other preparation projects were more effective.

It was a 1400 mile round trip drive from our home in Wisconsin to Pic River, Ontario, so making sure the trailer was in good working order was another essential trip preparation. I bought the Spindrift about six weeks before our vacation for $500 (My wife thinks I spent $450, but that’s another story altogether). I chose a daysailer after researching inexpensive, easily available, and seaworthy small sailboats. After reading plenty of old stories on the Internet about cool trips done in these venerable boats, I was happy to find our boat on the local craigslist for $600.

Since I’ve worked in a boatyard, I checked the boat from stem to stern and found it to be sound and dry. I sanded and oiled the age-blackened and neglected teak. I mounted a Nexus compass on the cuddy. Most importantly, Sarah and I sailed the boat as much as possible leading up to the Lake Superior trip. Sarah had learned to sail with the University of Wisconsin Hoofer’s Sailing Club. She also helped sail a Skipjack on the Chesapeake Bay while teaching children at Echo Hill Outdoor School. She is a cautious, competent sailor. Her skill exceeds her confidence level, which is a good attribute in a wilderness sailing partner.

We were approaching Pointe Canadienne, and the headwinds were becoming too much. We put in the reef after dropping the jib. There is no good protection on the weather side of the point, so we turned tail and headed for the protection of Bonamie Cove. We had made about 9.5 nautical miles, but it was still early in the day. Once we were tucked safely into the western lobe of Bonamie Cove, Sarah succinctly said, “This is not a vacation,” and walked away toward the comfort of her sleeping bag. Sarah needed to be back on time to teach a Yoga class at the University’s Southeast Recreational Facility, to finish some research projects, and to prepare for a trip to visit family in Pennsylvania.

It had actually been a fine trip, but the anxiety of making our daily mileages and fretting over either too little or too much wind made the trip more stressful than we would have preferred. A not so small component of our anxiety was the knowledge that although the Daysailer is a very seaworthy boat, you really don’t want to capsize one, as they’re very difficult to self-rescue. Some might say that the Daysailer is not an “open” boat due to the cuddy, but all I have to say to that is if a Daysailer capsizes, the cuddy fills with water. This makes it an open boat in my book. Having our 25 gear-and-food-filled dry-bags lashed in around the centerboard trunk made the boat stiffer than usual, but we sailed conservatively.

The first day, from Pic River to Shotwatch Cove, was a short one after we drove from Wawa, rigged, launched, and loaded the boat with our gear. The ramp at Pic River is a decidedly spartan affair—a gravel slope out from shore into the river with a giant log chained in place as a wharf. As we sailed out of the mouth of the Pic River into Lake Superior the seas were lumpy, and a light eight-knot NW wind pushed us along through a drizzly overcast day. We made ten nautical miles and camped in the protection of about ten islands just south of Shot Watch Cove. The cove got its name from an artifact found at an old trader’s cabin there. If you haven’t guessed, it was a pocket watch with a bullet hole through it.

The Lake Superior shoreline consists mainly of Precambrian shield granite, which is some of the oldest rock on the earth’s surface, covered with northern boreal forest. Black bear, moose, fisher, marten, wolves and even a small endangered population of woodland caribou inhabit this wilderness. At over 2,200 square miles, this natural wonder is larger than the state of Rhode Island and almost the size of Delaware. Although we didn’t see any of these large mammals, we did see the tracks or other sign of each animal at least once during the trip. We saw many species of birds: red-eyed vireos, yellow warblers, bald eagles, herring gulls, mergansers and loons. We were serenaded by the spirited wails of loons many nights in camp.

Sarah and I sailed from Shot Watch Cove to White Spruce Harbor on day two. Winds started light and shifty from WNW-NE before strengthening and filling from the NNW. Our boat speed was faster than we expected and after crossing the mouth of Oiseau Bay, the wind built. We took down the jib. Sarah checked the GPS and determined that we had gone farther along the coast than we thought. It was with urgency that we turned landward and spilled as much wind from the main as possible.

One of the themes of the trip was, “Watch out for sunkers.” It’s a word I picked up from a Farley Mowat book, The Boat Who Wouldn’t Float, which describes rocks just under the surface, which ... well, you get the idea. There are many rocks just under the surface, waiting (I’d say lurking if I wanted to be melodramatic) for a careless mariner on these shores. Sarah became quite good at spotting the disturbed water around sunkers, and I’m happy to report that we never did hit one. On the way into White Spruce Cove with 25 knots of wind and an unusual number of sunkers all around, I have to admit I had a lump in my throat hoping we wouldn’t have to jibe to lay the northern promontory at the mouth of the cove. We didn’t have to jibe, and it is always a deep feeling of relief to sail from turbulent to protected waters. We’d made about 12 nautical miles in about four hours.

As at Shot Watch Cove the night before, the beach at White Spruce Cove was covered with the unmistakable tracks of moose. Sarah and I hiked a short distance from the shore along the coastal hiking trail. We found a beautiful stand of white spruce on an ancient beach ridge. It was like walking through a pilloried cathedral, with yellow warblers flitting from tree to tree catching insects in the moss and lichen on the trunks. When we landed at White Spruce Cove, I had pulled the bow of the Spindrift up onto the beach and tied a bowline to a tree on shore.

I’d like to say we sailed from White Spruce Cove to Cascade Falls on day three, but in actuality we motorsailed. If you’re scratching your head, wondering what kind of motor we had, it was a “one Matt-power” coupled to a Carlisle canoe paddle. Yes, you read correctly, I helped us along most of the day paddling while making outboard noises for Sarah’s entertainment. At one point I took requests for the various noises an outboard makes when a mishap occurs like hitting a rock, losing a propeller, or running out of gas. I then had to explain that boating with my dad while growing up, I’d heard just about every sound an outboard makes when in its death throes. We made a hard-won 9.5 nautical miles to Cascade Falls.

The bay in which Cascade Falls sits is unprotected from the prevailing west wind and swell. We were able to camp there since the winds were light. I anchored the Spindrift bow out toward the small incoming swell and ran two stern lines to rocks and driftwood on shore. Cascade Falls tumbles about 45 feet from a granite cliff into Lake Superior by three main channels. The brook trout fishing here was pretty good and I caught several small trout in a pool above the falls. Sarah and I fell asleep to the rumbling sound of the cataract. Water is one of the greatest forces shaping this landscape. From the frozen water of the last ice age to the rivers or creeks running from inland to Lake Superior, and the lake herself, water has shaped and continues to shape this coastal world.

Day four dawned sunny with light steady winds 3-5 knots out of the SE-SW. Sarah and I got an early start, hoping to get some mileage in before the forecasted 20 knots from the SW filled in. While we were bringing the Spindrift in from anchor, a curious river otter swam close to the boat. We regarded each other for a moment before he swam off into Lake Superior. A 30-foot Beneteau we’d been seeing every morning for the first three days came out of Otter Cove and crossed our bow as we sailed down the protected east side of Otter Island. Once we sailed past Otter Head and back out onto the open lake, Michipicoten Island came into view for the first time. Michipicoten Island is approximately 14 nautical miles long by 7 nautical miles wide. This island was once used as a base for a lucrative lake trout and whitefish fishery, and even today fish tugs can be seen going out to collect nets around the now wilderness shores.

The winds rose above the predicted 20 knots and up to 25 knots sustained, the S wind funneling between the mainland and Michipicoten Island. We ducked into Bonamie Cove. Although the natural beauty of this wilderness is the cornerstone of a trip to this area, the human history of the region is a rich tapestry. Many names on the area map are French. The 1600s saw the French Jesuit missionaries traveling the area to “save the souls” of the Ojibwa Native Americans. French-Canadian voyageurs plied these waters in 40-foot birch bark canoes. Eight to ten wiry voyageurs would paddle 60 fur bales weighing 110 pounds each up to 45 nautical miles a day racing the short summer to make the trading journey from Montreal to the western end of Lake Superior.

Protected in Bonamie Cove as the winds rose to 35 knots, I ventured a guess that, “Good Friend Cove,” was indeed as good a friend to the voyageurs as it was to Sarah and me.

The remainder of day four was spent in the tent listening to the wind roaring through the trees on the ridge above us. Being trapped by weather was actually calming. The weather made all decisions for us, and we weren’t sailing. We woke up at dawn on day five to thunderstorms passing to the north and south of our campsite.

The winds backed to the west and continued to blow at 35 knots. The 6-8 foot swells driven by the wind were starting to smash on the rocks at the mouth of Bonamie Cove, throwing white spume high into the air. A hollow boom met our ears every ten minutes or so as a larger-than-usual wave crashed on these rocks. I anchored the Spindrift bow out from our beach. The large waves reflected around the point at the cove entrance and made it all the way to our protected beach still one foot high. Nudged by wind and waves, the Spindrift rode it out proudly, tugging playfully back and forth between the anchor line and stern lines in a slow easy sashay.

Sarah worked at a seashell cross-stitch, and I started dreaming of my next boat to while away the time. I listed all the positives and negatives of the Spindrift and began drawing boats. Between my sketching or list-making and Sarah’s cross-stitch, we read to each other from The Oxford Book of Sea Stories. Sarah’s favorite story was The Open Boat by Stephen Crane. Although Crane’s is a classic, I enjoyed Initiation by Joseph Conrad. The winds continued to roll through the trees, and the crash of the waves still met our ears. Lying in the tent, we were snug and safe in our perfect cove.

Day six dawned and the swell was still catapulting 20 feet in the air as it struck the rocks at the mouth of the cove. The wind had abated to 15-20 knots. Sarah and I began packing up inside the tent; we couldn’t really afford yet another day being weather-bound and still make the remaining 40 nautical miles to Michipicoten Harbor in eight days. Sarah and I looked at each other as the bellow of the wind increased. The wind rebuilt to a sustained 25 knots and gusted over 30. We un-stuffed our sleeping bags resigned to our second full day and third night camping in Bonamie Cove. We were happy we didn’t rush out since the wind increased to 40 knots for the remainder of day six. Tent-bound, Sarah and I talked about the strain of the trip.

I had convinced (The actual word Sarah used was “manipulated”) Sarah to come on the trip by saying, “Look, if we have four 20-mile days, we can do the entire trip in five days. That leaves us three extra days.” Anyone who paddles, rows, or sails small boats knows that my arithmetic didn’t add up. Fortunately or unfortunately, whichever it is, my faithful wife didn’t know any better and agreed to go. With plenty of time on our hands, Sarah and I talked about the mistakes I had made in convincing her to come on the trip. The good news was that it was mainly the timing of the trip and not the trip itself that was causing Sarah so much distress. Although one weather day was cathartic, two began to create more urgency.

A new concern began to creep into the back of my mind. We had filed a float plan with Pukaskwa National Park. We needed to call and inform them that we were safe by the end of day nine, or we risked having the Canadian Coast Guard searching for us. After completing kayak expeditions throughout the world without any problems, the idea of having the Coast Guard looking for us in my own backyard concerned me. I am very self-reliant, pride myself on my preparation and planning and I never want to be an example for critics of small boat expeditions.

Day six was spent much like day five. Sarah cross-stitched or read her book. I drew new small sailboats and made all sorts of lists. We would talk and then read again from The Oxford book of Sea Stories. This time we enjoyed Mocha Dick by J.N. Reynolds, which is a story that helped inspire Melville to write Moby Dick. It’s amazing how fast time passes when you’re drawing, daydreaming, and reading about boats.

On the early morning of day seven the winds were light. Sarah and I paddled out of Bonamie Cove and met a five-foot residual westerly swell. A steady, but light W-NW wind filled and began pushing us SE as the seas abated. We wanted to make miles, but we wanted to do it safely. The wind built all day and after 19 nautical miles we were sailing under main alone with three and a half foot breaking waves coming from astern. The winds had crept up to 25 knots slowly, and we found ourselves carrying too much sail area. Sarah went forward to the mast and dropped the main as I continued to steer. It was a tense moment, but Sarah worked quickly and efficiently. We sailed into Cairn Point Harbor under bare poles with the Spindrift riding the quartering seas safely. It was a lesson that would later prove valuable.

The land inside Cairn Point Harbor was either rocky or swampy with nothing in between. We set up our tent inches from the water’s edge on a steeply sloping cobble beach. The Spindrift was anchored with her stern about four feet from the vestibule of our tent making it easy to keep an eye on the boat. Luckily the harbor was protected, and waves never quite reached our tent. It wasn’t the best night’s sleep on the trip, as Sarah kept sliding toward the water as she slept while I tried to hold on to her as I slept.

Shortly after setting out on day seven we passed out of the southern boundary Pukaskwa National Park. After rounding Ganley Point and turning east toward Michipicoten Harbor, it felt like we were on the final stretch, with a good day’s sail behind us.

Day eight began cloudy with W-SW winds already blowing 15 knots. We broke camp and set out on a broad reach under jib alone. The swell was still about two to three feet, and as the wind built the waves did likewise. When we reached Point Isacor, the wind had reached 25 knots and Sarah went forward to lower the jib. We looked for a cove to duck into, but there weren’t any protected coves from the SW wind along this coast. Sarah checked our speed on the GPS. We were making between 1.8 and 2.4 knots under bare poles. The Spindrift’s stern was rising to the still-building three to four foot swell without taking on any water, so we continued on under bare poles to False Dog Harbor. We averaged two knots for 8 nautical miles and made False Dog Harbor just as the fetch became such that the breaking waves at our stern were beginning to make me nervous.

We had covered 16 nautical miles. The protection of False Dog Harbor held a beautiful crescent of fine white sand at the head of the bay. Large timber and stone wharf cribs could be seen under the emerald green water, harkening back to a time when loggers used the harbor to load timber on ships for points throughout the Great Lakes. The wind shifted NW and continued to blow at 25 knots. From the rocky point at the mouth of the harbor I could see the massive Perkwakwia Point 14 nautical miles east. It juts two nautical miles south-southeasterly into the lake from the mainland and protects Michipicoten Bay. Red squirrels chattered angrily at our intrusion as we relaxed on the beach after a strenuous day of sailing.

The forecast for day nine sounded somewhat schizophrenic, but Environment Canada finally settled on E winds of 10 knots, building to 15. Almost every day of the trip, the winds we encountered were at least 5 knots higher than those forecasted. In the morning of day nine, the wind was E about 8 knots. We tacked into the headwind for about 45 minutes when the wind went light. Thankfully, and perhaps miraculously, the wind began to fill lightly but steadily from the W-SW. It was probably only about 5-7 knots of wind, but it just blew and blew all day.

My dismay at the headwinds, which made the end seem so far away, was replaced by quiet optimism as the SW winds kept whispering us toward the growing profile of Perkwakwia Point, Michipicoten Harbor and home. The final obstacle as we cleared the abandoned light station on Perkwakwia Point was the mouth of the Michipicoten River, where the currents were strong and an evening release from the hydroelectric plant had made them even stronger.

Because of a sand spit constricting the river mouth, the currents were accelerated through the narrow opening. Sarah first steered us into the center of the current, where we tried motorsailing up the channel. When it became apparent that our one Matt-power couldn’t overpower the current ripping into the lake at 5-6 knots, Sarah steered us close in to the sand spit across the current. When we reached shallow water at the tip of the spit, I jumped into the water to pull us through the narrows. Once through, we hugged the shoreline where river currents were slowed by friction until we cleared the narrow mouth. A local man, sitting on the porch of his cottage a little way up the river, complimented us on how we had managed the river mouth as we passed. We were finally safe in Michipicoten Harbor, and the Coast Guard wouldn’t have to organize a search. •SCA•

Matt Magolan has been fortunate enough to live most his life on the water. He has made boat-borne expeditions to Hudson Bay, Norway's Lofoten Islands, and Revillagigedo Island in Alaska. He currently lives in Madison, WI with his wife Sarah, who is keeping him around for the time being, even though he fools her into crazy trips sometimes.

First appeared in issue #63

Matt and Sarah, now you have the rest of your lives to say, "yep we did that!" I'm always wanting a comfortable fair winds trip, but it never really goes that way. To me it is the memories of the challenges and overcome obsticals that make the trip memorable. Your last day seemed like a gift given for the overcoming the challenges of changed plans, making good descicions and living with them. And now Matt, well you have already started, to find "that" boat perfect for your surrounding waters! Thanks for sharing your trip.

Great story. Go, Badgers.