Article by Josh Colvin and Rick Landreville

THE IDEA

Josh: The last time I participated in the Texas 200—in an 8-foot plywood PuddleDuck in 2014—I said it was the worst thing I’d ever do again. Although I had mixed emotions about the experience, I recognized that cuts and bruises would eventually heal, the post-traumatic stress would dissipate, and I’d be left with mostly good memories. And that’s pretty much what happened.

But another reason I was reluctant to do it again was precisely because the first time had been so perfectly absurd and memorable. Nothing I’d do next time was going to compare with a week of sailing a fleet of hastily-built tiny boats in 30-knot winds with the incredible bunch of characters assembled in 2014.

In the years following I’d been thinking a lot about the accessibility of small-boat adventure and minimalist cruising, and how there are really two types of leisure classes. We all know about the wealthy and their access to travel and exploration, but it’s been my experience that having almost no money might be a better recipe for adventure than having a lot. If I hadn’t known it already, my first Texas 200—sitting right down on the water in a cheap box-of-a-boat, sleeping under the stars on the beach, and being utterly engaged with my surroundings—taught me that.

One of the projects I’d been working on recently revolved around the idea of loading a bunch of small boats into a container and shipping them to Ireland, where we’d fly over, unload the container, and set sail, camp-cruising on our own vessels. This eventually led me to wondering whether it might make sense to save the cost of shipping or trailering a boat to distant events like Texas 200 and instead buy a local boat. Of course the boat would have to be cheap or it wouldn’t make sense. How about the Texas 200 in a $200 boat? It did have a nice ring. And with that I was committed to heading back for another round.

One of the best things about my first 200 was the camaraderie, so I knew I wanted to share the misery with someone. Turns out the list of people keen to spend their vacation time down in Texas, in June, sailing a $200 boat, is relatively short. I might have been able to lure in a non-sailor of course, someone who didn’t fully understand the perils, but I also knew I might need help getting the boat from start to finish and surviving. So I grabbed the low-hanging fruit and sent a note to Rick Landreville, my buddy from Canada who’d done the 200 in a Duck with us in 2014. He had already proven to be the right mix of capable and crazy, so I wasn’t all that surprised when he wrote back saying, “Sounds great!”

Rick: Out of the blue, I get this e-mail from Josh. “Hey Rick, I got this idea of doing the Texas 200 again.” E-mails like this are seldom good, because I am a sucker for adventure. “I’ve kinda been going through the list of people I know, and thinking, ‘Who is the craziest bastard I know who could actually pull this off’ and I thought of you”

Lofty praise indeed.

Josh and I only have a few things in common; A love for small boats, a love of adventure, a strong sense of family, and a love of CBC Radio. We’re also within a few years of each other in age, but the similarities end pretty much there. The prospect of spending almost ten days mostly within three feet of each other was cause for pause. I have gone adventuring with an eclectic mix of people over the years, and personality conflicts can make or break a cruise.

We needed to discuss the type of boat we were going to try to acquire—maybe an O’Day a Potter, or perhaps a Pelican? Nope, been there done that. The Texas 200 has been chock full of those types of boats. What about something homebuilt, like a Michalak design? Putting my life on the line in something someone else built, and has given up on or abandoned, seemed foolish, even by my standards. It was about then one of us spotted a C-Scow on craigslist. $200 including a decent trailer. A C-Scow? How perfectly unsuitable! A shallow draft lake racing boat meant for tearing around the buoys on Midwestern lakes? Perfect, let’s do it.

Chuck Leinweber made the trip into Dallas, where the boat was located, and dragged it back to Magnolia Beach for us. All we had to do was fly in, make a few repairs and modifications, and go sailing for a week. What could possibly go wrong?

We had the mainsail packaged up and sent to sailmaker extraordinaire Bill Tosh who added two rows of reef points and shipped it back to Magnolia Beach for our arrival. C-Scows do not come with any reefing provisions, so ours might be the only one in existence.

Then Josh sends me another email; “I’ve been talking it over with a few of the Texas 200 executives, and we’re thinking about doing the event the wrong way” The wrong way? What does that even mean? My experience with the Texas 200 is in a 4-foot by 8-foot Puddle Duck—you don’t get much more the wrong way than that.

“No, we mean sailing it from Maggie Beach towards the starting point. Upwind.”

Now this was getting interesting.

We purchased our plane tickets, and managed to get on the same plane leaving the same airport at the same time, but our seats were one behind the other. Coincidentally I ended up seated beside a lady who happened to be an experienced multihull racing sailor. As Josh and I talked back and forth about details we still needed to iron out, the lady looked more and more bewildered. “So, you had your boat shipped down for the event?”

Nope. Bought if for $200 sight unseen.

“$200?”

Yup, trailer included.

“So you guys are experienced C-Scow sailors?”

Nope. We’ve never seen one.

“And the event is 200 miles in high winds?”

Yep.

“Is there a chase boat?”

Nope.

“You guys are nuts.”

Josh: I especially enjoyed how this conversation evolved. When she first heard we were sailors headed for a week-long event she asked us if we happened to know several, presumably well-known, sailors she was acquainted with, but Rick kept saying, “Nope.” Then she asked those other questions about where we’ll be sleeping, the condition of our boat and so forth, and I can see her shaking her head. At one point I remember Rick was trying to better explain the Texas 200 and he asked her if she’d ever seen one of those pig races at the county fair where the hogs run off in every direction.

PREPARATION DAY

Rick: Texas 200 hundred gurus Chuck Leinweber and Bill Moffitt picked us up in San Antonio Friday evening and we drove four hours to our boat and starting point. It was dark when we arrived, but we could just make out the low silhouette of the Scow under a tarp in the driveway. “We’re thinking of starting the event on Sunday instead of Monday,” Chuck says, “to take advantage of the weather forecast.” This leaves us with one day to refurbish the boat so that it might survive six days of hard, upwind sailing.

“I’m sure it’s probably in decent shape,” we lie to ourselves as we turn in for the night.

The next morning, sleep-deprived from the time difference and travel, we pull the cover off the boat. The mast is enormous, towering 30 feet above the hull. The paint chalked and faded. The standing rigging a rusty, kinked mess, and the running rigging so deteriorated from the sun that some of it dissolves into a powder when we touch it. The hull is stress-cracked and spidering at the deck fittings, and most of the blocks have been replaced years ago with cheap, zinc hardware-store pulleys. I have my first serious pangs of doubt about then.

Our friend John Goodman, also doing the event the hard way, jumps in and we all get to work. We build plywood washers to back up all the hardware so it won’t pull through the weakened fiberglass. We tighten all the fittings, replace running rigging as best we can. We consider changing the standing rigging, but there’s no time so we hold our breath and leave it alone.

We pull out and set the mainsail. There is at least an acre-and-a-half of Dacron up there—way too much to comfortably sail in high winds for six days. Fortunately we’d anticipated this and had the reef points, but when we tie-in a reef the shape looks awful. With the footed boom, there is no neat way to deal with the extra material from the reef.Remembering my lugsail tuning tricks, I decide to try the sail loose-footed and rig up an adjustable outhaul. We tie the nettles above the boom, set the outhaul, and it all looks decidedly better.

Chuck’s neighbor trailered us to the ramp and we were in business. Unfortunately, by the time we’d bounced our way over the launch parking lot, the centerboard block had completely broken away from its attachment point on the bottom of the hull. Another 45 minutes of MacGyvering and I had it repaired. Now we were fresh out of excuses, so we launched the boat.

AND WE’RE OFF

Josh: Chuck’s neighbor, Jim Haynie, was a local sailor and retired Marine officer—thoughtful, measured, and fastidious— he kindly leant a hand wherever it was needed. I could only imagine what he was thinking as we were untangling our new boat for the first time 24 hours before our scheduled departure. The next morning after we’d gotten ourselves better sorted out he stopped by again and was looking things over. Thinking we might have made a believer out of him I asked, “So what do you think?” He paused, looked at the boat again, then up at me.

“I think you guys have a lotta balls.”

Hours later when we finally sailed away from the dock I was relieved, but with hardware having literally fallen off minutes earlier, I can’t say I was bubbling over with confidence. And it didn’t help that we could already see water seeping in around both bailers.

Before long we were hard on the wind working into a little chop. The Scow was a real drama queen in these conditions. Where we could see other boats just slicing along effortlessly, the flat-bowed C-Scow would respond to every third wave with an absurd overreaction—shooting spray into the air like a water cannon, raining down over the entire cockpit. With water coming in from over the bow and from various spots in the hull, we had no way of distinguishing the exact origin of the 15 gallons of water that was perpetually sloshing around our cockpit.

Rick: All the foils were heavy metal plates, and they kicked up, which is very important for a shallow-water event such as this. However hoisting and lowering the boards was difficult, because the repair I did at the boat launch left the port board with only 2:1 purchase, so it took almost 75 pounds of force to yank the thing into its case.

On the long upwind slog with a big fetch, the C-Scow would show flashes of windward brilliance, followed by cranky, pig-rooting periods. It was tough to find the groove, but rewarding when you did. As we got past the Port O’Connor jetties and started to close in on our destination at Pass Cavallo, we grounded out on a sandbar that didn’t appear on Navionics, nor the fishing maps we were using. It’s a strange sensation to be that far from land in calf-deep water walking the boat.

We seemed to make a habit of rolling along at seven knots, then grinding to a halt unexpectedly or almost capsizing within site of camps. Josh and I would look at each other, and in our softest voices say simultaneously, “So close. So close.”

Josh: We didn’t talk much that first day, probably because we were waiting for the other shoe to drop. Our biggest concern was that some critical fitting would let go and we’d lose the rig, so we spent a lot of time looking up.

We were about 20-miles in when something finally broke, but it was only the mainsail outhaul and, serendipitously, the beach we ran to for repairs turned out to be the designated first camp. Just liked we’d planned it.

Rick: At camp that night, we were able to meet up with the half-dozen other boats doing the course the wrong way. The camaraderie is one of the big draws on this event.

We’d taken turns at the helm the first day, but as I’m quite a bit a bigger than Josh, it made sense for me to handle the twin boards and do more of the hiking out while he took the helm. This was more or less our arrangement for the rest of the trip.

We also decided that unless the winds dropped to near zero, we’d retain the double reef we had tied-in. We weren’t planing yet anyway, and the boat was doing hull speed the entire time, so we figured we reduced the stress on the rig and hull by keeping the reef in.

Josh: Did you mention the running back stays? On tacks, and especially jibes, the C-Scow needs to have one stay freed and the other tightened. Not a big deal, but you can imagine what happens in a high-wind maneuver when you forget and the boom comes flying across and hits the stay that hasn’t been released. Don’t worry, more on that later.

HEAT AND GENERAL MISERY

Josh: The wind is often howling, the seas can get rough, and there are myriad sharp things, marine traffic, and wild creatures to worry about, but I think most Texas 200 veterans agree that sun and heat are the biggest concerns.

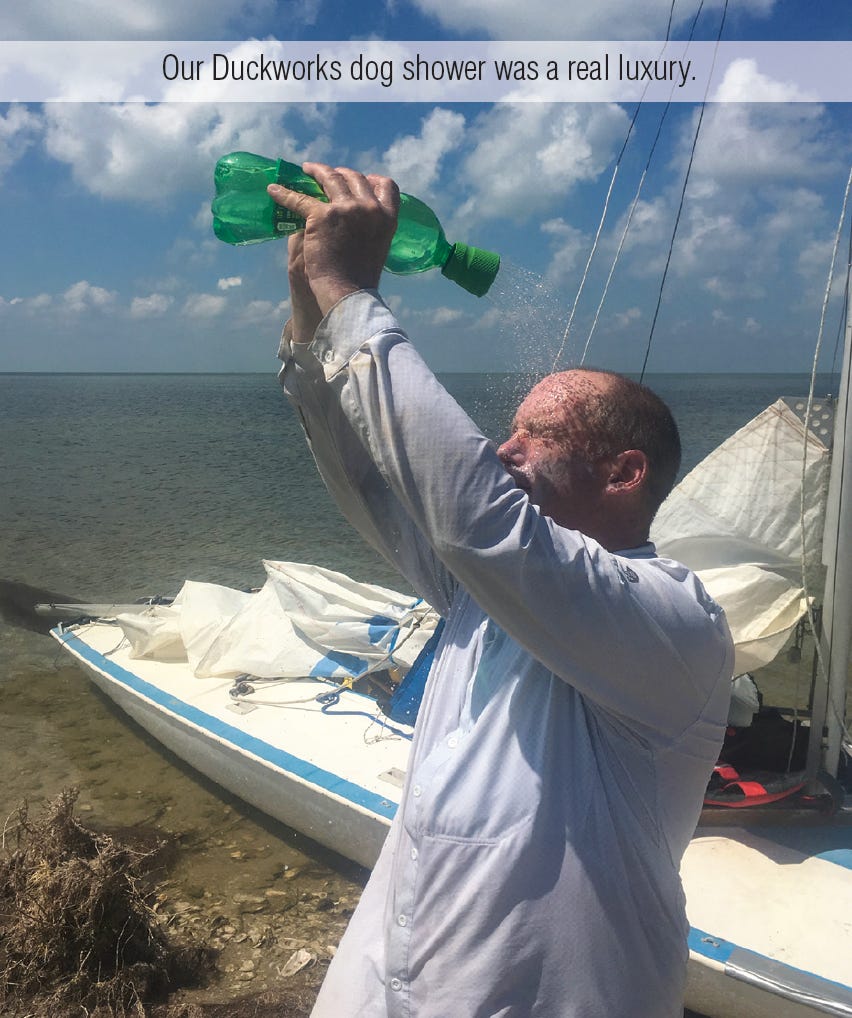

I don’t know how hot it got this trip, in part because I didn’t bother listening to the weather radio (let me guess, it’s going to be hot and windy) but it didn’t seem as bad as the last time. But on the second day, three boats (us in the C-Scow, Chuck and Bill in their Michalak Toon 19, and John Goodman in his Goat Island Skiff) decided to make more miles and push on past the planned group campsite to a desolate marshy strip of land called Panther Point, and I think that must have been the hottest day.

Unfortunately, this swampy finger of land was also the first place we encountered serious mosquitoes. So just as the sun was mercifully setting, I started getting bitten and decided to escape to my tent. Problem was the breeze had mostly died and my tent had been set too early and allowed to bake in the sun and retain heat. I tried to lie still but eventually found myself checking my own pulse and wondering if I might die here. It got so bad I decided I had no choice but to reorient my tent to catch what little breeze there was, which required my naked exit followed by an hour-long battle killing mosquitoes that chased me when I crawled back in.

It seems like I’d just fallen asleep when I woke to a bright moon coming up over the horizon, its light showing through my tent wall. I recognized this had the potential to be a pretty special photo—a moonrise over our beached boats and tents—so I decided I’d dig around for my camera and try to get the shot.

But as I groggily searched my pack I noticed the moon was getting brighter and bigger at an alarming pace. And then I heard the distinctive wump wump wump sound of a helicopter approaching. Was this the Coast Guard on patrol? Was this a military helicopter doing target practice on a desolate uninhabited stretch of land where no sane human would ever be?

I unzipped my tent and poked my head out for a better look. The helicopter was coming in very low and it had a multiple bars of headlights turning everything in its path white, water churning up all around. Then I realized it wasn’t a helicopter at all—it was an airboat. As it got closer the noise became deafening, the giant blade spinning, a separate outboard engine screaming. I was mostly blinded by the array of halogens, but in silhouette I could see the driver was sitting atop a custom-welded bridge (wearing a leather mask I assumed) lording over several crew who were stabbing at the water with giant tridents.

I unzipped my tent and poked my head out for a better look. The helicopter was coming in very low and it had a multiple bars of headlights turning everything in its path white, water churning up all around.

By now Rick had popped his sunscreen-covered face out from his tent and even though it was too loud for us to talk, I gave him a look that said, “Do something. Save us!” He surveyed the scene for a few seconds, appeared to shrug his shoulders, then zipped back into his tent. That’s it? I thought. We’re in the middle of some sort of Mad Max apocalypse and Rick is going back to his inflatable pillow for a few more winks?

Fortunately, the doomsday contraption didn’t run us over, they just worked their way along the shallows, stabbing at the water furiously as they passed. In the morning I asked Texan John Goodman, who hadn’t bothered to come out his tent, about it, and he said what we’d seen was an airboat “gigging for flounder.” The flounder apparently get cold at night and move into the warmer shallow water where trident-wielding crews spot their faint outlines in the sand. I was just happy fish were the only thing killed that night.

MUD ISLAND AND CIVILIZATION

Rick: After a few days, we settled into the boat, the routine, the heat, the wind and the bug bites. We were able to get to where tacking was silent and effortless. Josh would scoot forward slightly, I’d slack the windward running backstay, and grab the leeward backstay. The tiller would ease over, and I would release the uphaul for the soon-to-be leeward board, while pulling up the other board on my way across the boat. Josh would straighten the tiller, fall off slightly with the mainsheet then gather the boat up as I hardened the other backstay. A miss on either of our duties would make the flighty lake racing boat bury the rail, so we had to be accurate. What we did find was that when we got it right, we were one of the fastest boats in the fleet.

On the fourth day, we made our way to Mud Island—our home for the next two nights. Ironically, the poorly named island was the nicest and most scenic camp of the trip. It has an almost-sand beach (composed of finely crushed shells), flat tenting areas, and a nice backwater marsh that was home to numerous shorebirds foreign to us Pacific Northwesterners.

From here, we were able to venture into civilization at Port Aransas. We sailed across towards town, and beached our boat with John (Danger) Goodman’s Goat Island Skiff and hopped into Chuck Leinweber’s Toon 19 with Bill Moffitt and went to replenish some supplies. Five men in a boat like that meant dousing the sail, and putting the little 2-horse Honda to the test. I wouldn’t say we were unsafe, but I doubt I would’ve put my wife or children in that boat in a busy seaway with that much weight, wind, and waves.

After four days of rustic camping, and vigorous sailing, we must have been a sight as we pulled into the marina. After getting our supplies, and a decent lunch at a local restaurant, we headed back to our boats, and back to Mud Island. It almost seemed more normal to be in camping mode, than back in town. I was grateful to return.

After the first night we had raced ahead of the wrong-way crowd and there were just our three boats. The plan was to meet up with the rest of the “wrong way” and “right way” boats at Mud Island that evening. Our secluded beach wasn’t so secluded after 63 boats pulled up to shore! The revelry and talking went long into the night, but our loose group of three boats went to bed early. We had a plan…night sailing!

NIGHT SAIL TOWARD ARMY HOLE

Josh: I had expressed a desire to do some night sailing on the Texas 200 and Rick, Chuck and Bill were all keen to do it as well. Before the event started Chuck had pointed to this morning when we’d be leaving Mud Island and heading back downwind on our longest day on the water (50 miles) under a decent half-moon, as maybe our best chance. Now here we were. In a quick meeting by our tents that evening we agreed we’d all wake up at 3:00 a.m., get our two boats rigged, and sneak off in the moonlight ahead of the rest of the fleet.

Rick and I crawled into our tents fairly early. I tossed and turned thinking about the impending night sail, wondering if it was a smart idea given the state of our boat and its tendency to identify as a submarine off the wind. Based on the snoring coming from his tent, Rick was significantly less concerned, but when I woke him up at 3 a.m., with the wind already snapping at our tent fabric and the moonlight mostly obscured by clouds blowing through, I told him I was having second thoughts about leaving so early and setting off into several hours of darkness. He shared my concerns but we both knew this was a chance to make a great memory.

I walked over to Chuck and Bill’s tent to see if they were up and they were already methodically packing sleeping bags by red headlamps. I told them about our mixed emotions and Chuck said they’d already deflated their air mattresses, so they were going, but he suggested we could leave whenever we wanted and just meet them at Paul’s Mott, a point of land we’d all pass on our way to the day’s destination, Army Hole.

Rick and I couldn’t go back to sleep now, so in the darkness we watched as Chuck and Bill sailed, barely visible, out through the anchored fleet under mizzen alone. Their boat cutting out silently was so captivating we knew in that instant we needed to follow suit. So after a little strategizing we broke our tents down, packed the Scow, walked it to deeper water, and raised sail.

The next couple of hours were largely instrument flight rules, as we negotiated shallows and navigated by GPS and aiming at particular stars. It was a spectacular and smooth sail, slipping along quietly, all alone except for a couple shrimp boats working Aransas Bay.

After meeting the guys at Paul’s Mott we all pushed on since this was going to be a long day. As the winds increased, Rick and I began to push the boat a little harder. We’d made it this far, so our confidence was growing. Before long we’d stretched out far ahead of Chuck and Bill but we could see another boat running parallel coming in off the Intracoastal Waterway.

We didn’t think much about the other boat at first, but every time we looked up they were right there, pacing us. Reflexively we hardened up sheets, hiked out a little farther and started paying closer attention to puffs and wind direction.

The speed of the other boat made us suspect it was a multihull—it was flying—but when our courses finally crossed and they fell in just behind us we saw it was Hamilton Cowie and John Rudden in their O’Day Daysailer Reservoir Dog. They were whipping that boat for all she was worth, hiked out, a streak of foam trailing behind.

Rick and I fell mostly silent, focused. Not wanting it to look like we were racing, I’d ask Rick how close they were and he’d casually glance over his shoulder. “Close,” he’d say, but somehow, some way, we managed to hold them off and arrive at Army Hole first. As Hamilton and John pulled into the reeds just behind us we gave them a thumbs up and they returned the compliment. Although we’d been racing we weren’t sure they were paying us any mind. But when we saw them later they confessed.

“Are you kidding? We were saying ‘I’m sure they’re very nice guys, but right now I hate them. They are the enemy. We must destroy them.’”

HORSE TO A BARN: THE LAST DAY

Rick: One of the disadvantages of leaving at night was that we were the first boat into the semi-abandoned military base called Army Hole, and, the first boat into shore was always one of the last to leave as the boats were crammed in like sardines, one behind the other. We finally got underway about 0730 for what should’ve been a 24-mile sleigh ride back to Magnolia Beach. The irony was that in 2014 we’d had the same high hopes and got our butts handed to us by the weather. This time, instead of no wind and an adverse current, we had way too much wind and choppy seas. The boats that left an hour earlier had much calmer winds into Port O’Connor, and skated into the lee of the channel islands without incident. We, on the other hand, were on the very edge of control and white-knuckled all the way across Espritu Santo bay.

At one point we were flying along downwind in a washing machine of confused waves, heading toward shallow water and dreading the inevitable jibe we needed to make. We conservatively opted for a chicken jibe, but as we rounded up and bounced over the top of one wave and down into the trough, I pulled up on the soon-to-be-lee shroud line, but instead of freeing itself from the cam cleat the line pulled the cleat mostly off. It felt and sounded right, but when we came through the tack the boom hung up on the backstay burying the rail and entire side deck in green water. When I realized what was happening I was able to free the stay, but we came close to dumping the boat.

Unfortunately our new course was not a friendly one as the Scow kept sticking its bow into waves.

“Okay. Options?” I ask. The choices were few; Drop sail and try to steer towards the ICW under bare poles. Cut a flap in the bottom of the sail to depower the rig. Or suck it up, and try to make the second opening of the ship channel into Port O’Connor. We chose the latter but, not wanting to jibe, missed the opening by about ten yards. We surfed up onto the mud beach and dropped sail, then walked the boat into the channel shielded from the winds by the land and buildings.

Later, back out of the channel and into the final run towards Magnolia Beach, a 14-mile stretch, we had a quartering wind of about twenty knots with gusts north of thirty, with foot-high waves running the same direction. This was the Scow’s best point of sail. About halfway there, for no apparent reason, the boat caught a gust of wind whilst at the crest of a rolling wave and started to plane. Now when I say plane, I mean lifting-the-nose-of-the-boat-to-the-moon planing. Our boat speed easily doubled and we were skipping along for nearly two solid minutes on only the last six feet of the boat. There were four boats well in front of us, and after the increase in speed, we caught right up. I don’t think it would be hyperbole to say we touched eighteen knots. It felt like thirty! It may have been a blessing we didn’t experience this earlier in the trip, because it was so exhilarating, we would have spent more time trying to replicate it and stressing the boat.

Once back at the start/finish line, we packed up the boat and our new friend Jim Haynie came to pick us up again. “Didja miss us Jim?” I asked. “To be honest,” he said, “I didn’t think I’d be picking you up at all. Not in one piece anyway.”

After a quick shower and clean clothes we went back to the beach for the shrimp boil and an exchange of stories. We had decided we’d donate the boat to the club, and let them auction it off on the beach after the event. The winning bid came in, and we bid adieu to friends and to the best and worst boat we could have chosen.

One Final Thought

Though we were successful and able to prove the concept of buying an inexpensive local boat for a distant event, we cannot recommend or endorse taking an untested boat to an event like this one. Things could have turned out very differently. In our case we had done the event before, had the help and support of several expert sailors and boat builders to prepare our vessel on short notice, we carried redundant provisions and safety equipment, and we had a series of contingency plans if things didn’t go well. •SCA•

First appeared in issue #108

"Instrument flight rules" - good one!

@josh and @rick

I at least skim every SCA article that comes down the pike, but this one really landed with me. Several reasons:

- I also love small boats and adventure, and seeing people 'doing the most with least' is both inspiring and genuinely interesting.

- This is 'hacker mentality' in its purest form! Not the common 'unauthorized computer access' definition, but the broader 'intentionally doing things and using things in ways for which they were not intended' definition. The boat, the course, and the adventurers...all authentically hacked! (or wacked?)

- All kidding aside, this should serve to inspire people (like me) who make excuses for not doing more raid/adventure type events (like t200, OBX, the watertribe events, etc) due to the logistical challenges and or not having events close to where we live. "I need to buy or build a boat that's fit for purpose. I need 2 days to trailer the boat to <insert far place here>, and 2 days to get it back." blah blah blahl. Its all BS/excuses!

"I just need to find a local boat, a healthy dose of common sense and small boat skills/safety knowledge, a plane ticket, and a relentlessly positive punk rock attitude" < this is the way.

I hope more people do this (safely, for it can be done).