This is a continuation of my Tech Bights column on solar cruising in the previous issue; and I discussed recent developments and manufacturers of electric outboards in Issue No. 136. If you have thoughts or stories about solar cruising, or additional ideas for solar cruising boats, please let me know about them.

Traveling faster using limited power – it’s not a new idea. As soon as steam and gas engines emerged from the workshops, clever mechanics used them to move carriages and boats faster than a man could walk, run, or row. During the first decades of the 20th century, both working and pleasure boats were driven by heavy, low-compression engines. To exceed their theoretical hull speed, many of these early gasoline-powered boats had long, narrow, low resistance hulls that were very similar to the steam launches of the previous era.

More recently, naval architects embraced these concepts to design a new generation of fast, power-efficient boats. For example, Nigel Irens, best known for his record-breaking trimarans and Gunboat catamarans, next focussed his attention on go-fast monohull powerboats with long, skinny hulls. He calls his design approach “low-displacement/length ratio,” or LDL design; and about a decade ago he drew “Greta,” a 26-foot LDL prototype that is reminiscent of British river launches from long ago. It has a slender hull with a 4:1 length-to-beam ratio, a plumb stem and a nearly flat bottom aft. Powered by a small diesel engine typically found in rather modest sailboats, it can cruise comfortably – without planing – at more than 11 knots, nearly twice its theoretical hull speed; here’s a video showing her getting underway. Irens’ “Elektra,” a more recent LDL design, is a “fast electric” launch that’s powered by a pair of 12-kW motors and carries over 700 pounds of lithium-iron-phosphate batteries, and an optional generator. It’s being marketed as a superyacht tender – with a claimed top speed of 30 knots.

But high-power electric boats that sport foils and sophisticated control systems have now become features of powerboat shows. Speed and sizzle, not efficiency or long running time between recharges, is what pays the boatyard – and advertising – bills. So where do those of us without superyachts, who might be interested in building an efficient solar cruiser, find smaller, simpler – and lower-cost – boat designs? William Atkin, his son John, and Phil Bolger, who all took full advantage of plywood to design slippery, low resistance hulls, immediately come to my mind. You can still check out many low-power designs from the Atkins – and their colorful design briefs – at atkin.mystic seaport.org. I particularly like those for “MoToSkiff” (15’ LWL), and for the narrow-beamed “XLNC” (18’ LWL) and “Russell R” (20’-6” LWL). And there’s also “Rescue Minor” (19’ LWL) with its Seabright surf skiff bones, shallow-draft, and ultra-low power requirements. A decade ago Kees Prins reinterpreted Atkin’s gas-powered tunnel-hull design and installed a 6.5-hp electric motor and 700 pounds of AGM batteries that were capable of driving the boat at 6 knots for up to 24 miles. Today, replacing those lead-acid batteries with current-tech lithium-iron-phosphate batteries could cut 400 pounds of ballast, and more than double the projected range.

Phil Bolger, the master of efficient low-cost material use, drew iconic, easily-driven cruising boats with significantly higher length-to-beam ratios. Bolger’s 23-foot “Sharpshooter,” a highly-flared square-tailed dory, and his iconic “Sneakeasy,” both have chines that run straight aft to support the weight of quieter, fuel-sipping, more environmentally-friendly, but heavier, 4-stroke outboards that were starting to be sold 40 years ago. With a long, narrow waterline length that is five or six times its width, Sharpshooter can achieve impressive boat speed with incredibly low power. Bolger writes in 30-Odd Boats that he observed over 10 knots using a rather modest 10-hp outboard; and 22 knots with 25 horsepower. That speed/length ratio is well over 2.5 – characteristic of a planing hull. Frugal power use, indeed, compared to today’s typically overpowered “hole shot” bass boats, and Sharpshooter looks like it would be a good candidate for electric cruising.

The almost-too-narrow, straight-sided Sneakeasy is Bolger’s homage to the barrelback gas speedsters of the early 20th century. In Boats with an Open Mind he says: “[Sneakeasy’s] long, perfectly flat bottom and plumb sides are optimum for keeping the wake flat. Almost all the water she displaces is moved vertically downward…So little pressure is needed to move it that far that practically no water moves sidewise in the form of waves. The wake is a flat carpet of foam from surface friction…Deadrise in the bottom would make whatever pressure is developed expend itself more to the sides, near the water surface where it would show up in waves.” According to Bolger, Sneakeasy will comfortably cruise at 10 knots – 50% higher than its displacement hull speed – with only a 7-½ hp outboard. And he claims that he hit 28 knots (well into scary planing speeds) with 35-hp hanging off the transom. This kind of performance is the direct result of light construction, low drag, and a very high length-to-beam ratio (L/B ratio = 7!).

Phil Bolger also designed a number of easily-built and easily-driven skiffs and motorboats with electric-cruising potential. Consider, for example, the hard-chined, flat-bottomed “Clamskiff” and the double-chined “Diablo,” both documented in Harold “Dynamite” Payson’s Instant Boats books. But lest you think that Bolger only drew gas-sipping runabouts, consider his 30’ cabin cruiser “Tennessee” (Design #359, described in Different Boats). This flat-bottomed power sharpie is a dimensional expansion of “Viper” (#358), Bolger’s recreation of a 1910 speedboat of the same name that was designed by Albert Hickman.

Both Bolger’s Viper and his Tennessee are skinny boats with 5:1 L/B ratios, and Tennessee was designed to be efficiently driven by a quiet, gas-sipping 9.9-hp 4-stroke outboard. Always a frugal designer, Bolger cleverly drew the topsides to fit four sheets of plywood, butt-jointed end-to-end, and he used external chines to simplify construction and keep the interior cleaner. The as-drawn cabin top is big enough to support the large 550W commercial solar modules that are now being manufactured. While originally designed with a soft shade over the rear cockpit (as found on many Chesapeake deadrise workboats), a hard top could provide support to double its solar power.

Phil Bolger and Albert Hickman

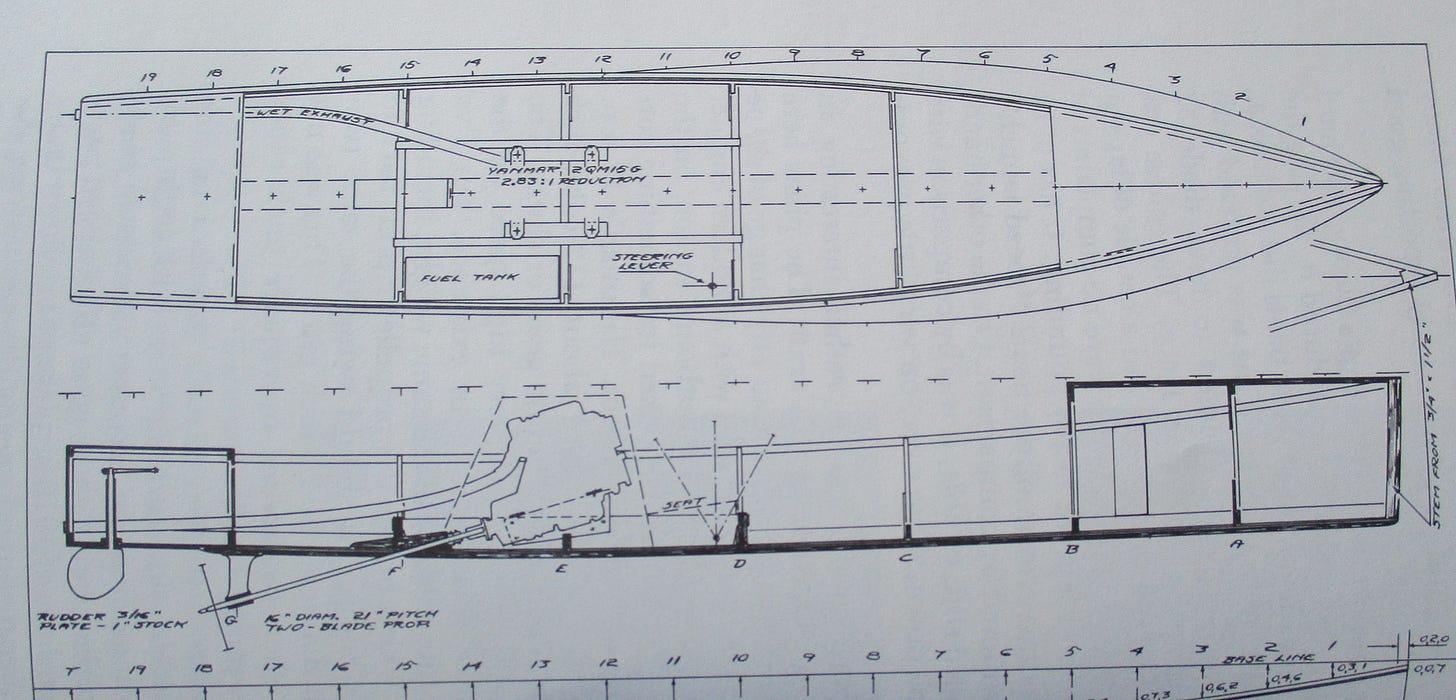

Although he preferred cheaper outboards, Bolger also designed slippery, power frugal boats with inboard engines, which can now be nicely adapted to electric propulsion. An example is his 20-foot “Viper,” his redesign of an Albert Hickman (the famed designer of the “Hickman Sea Sled” and inventor of surface-piercing drives) speedboat from 1910, when slow-turning, low-compression gas engines were “hot.” In contrast to the “barrelback” speedboats of that era, Hickman’s “Viper” was a narrow, flat-bottomed sharpie; and it ran over 18 mph (16 knots) – three times “hull speed” – with a direct-drive 12-hp engine turning at 1,100 rpm, and “showed very little disturbed water in her wake.” Bolger’s redesign for plywood is also flat-bottomed with vertical sides, and waterline length five times the beam. He projected that a small 2-cylinder 15-hp Yanmar diesel, turning a 16x21 “oversquare” prop with a 2.81:1 reduction, would give his “Viper” about 20 mpg at Hickman’s reported speed.

So what’s the trick for designing fast, slippery, low-powered boats? Thomas Firth Jones, a contemporary of Bolger, describes the basic strategy in Boats to Go, originally published as Low-Resistance Boats, a much more appropriate title. He writes, “In the beginning, there was no other kind of engine [besides steam]. Boats couldn’t plane because one horsepower is needed to lift every 50 pounds, and the engines alone had power-to-weight ratios hardly better than that. Designers had no choice but to use the…most effective way of exceeding hull speed: They made their hulls so narrow and sleek that they cut through their own bow waves, rather than ride up and over.”

For design inspiration, Jones looked to Weston Farmer, author of From My Old Boat Shop. Farmer grew up with “one lung” gas engines and the first-generation of outboards, and he was familiar with slippery, low-power hull designs. Starting as a draftsman at the old Elco Boat yard in Bayonne, NJ, he headed up the “yacht design department” when Elco began building PT boats during WWII, and he subsequently produced many traditional plank-on-frame boat designs. Farmer’s most iconic plans – and his colorfully written design briefs – are still available at Duckworks BBS (but good luck finding a copy of his book…). Take a look at “Irreducible,” an inboard launch powered by a bastardized “Ole Evinrude original” outboard, that’s only ten feet in length! And “Diana,“ a slippery 25-foot steam launch that could be readily adapted to electric propulsion.

Referring to Farmer’s low-resistance designs, Jones notes, “About twice hull speed, [Farmer] thinks, is a reasonable expectation if waterline length-to-beam is at least 5 to 1. He wants the bow half-angle fine but not pinched (no hollow in the load waterline), and low displacement: “...one horsepower will drive several hundred pounds of boat – say 10 horsepower per ton.” Jones continues: “In long, narrow powerboats, Farmer prefers a round bottom. Nevertheless, a semi-displacement hull, like a planing hull, is poorly supported aft once it moves through its bow wave and ahead of its stern wave. It needs a broad lifting surface aft, so the bilges must be tight bends, which are hard to make in many kinds of construction, and are often not durable. Chined hulls are simpler to build and stronger. They give more stability to a narrow boat. At speeds above hull speed, chines don’t increase resistance.” [emphasis added]

Jones envisioned an easy-to-build flat-bottomed boat with hard chines, like the Vipers of Bolger and Hickman. And he tested this design with a technique right out of “Captain Nat” Herreshoff’s Bristol boatbuilding shop: using a balance beam and the current of his local river to compare two 1/16-scale models. One was a “long, narrow, warped-V hull,” the traditional shape of a Chesapeake “deadrise.” And the other had a flat bottom. Both hulls had hard chines. Jones found that at less than hull speed the flat bottom might have had slightly less resistance. But at higher speeds the flat-bottom hull had twice the resistance of the warped-V hull; and “...the flat bottom would not exceed hull speed at all without lifting its forefoot and trying to plane.” Jones then built his 22’-5” “Puxe” with a slightly V-shaped bottom.It was a slender boat with flared, cleated-plank topsides, a sharp deadrise in the bow, a cross-planked bottom, and a nearly plumb stem. “She follows the well-known rules for chined designs: The less rocker the better, with perfectly straight lines in the aft third of the hull. The transom is ⅞ of the maximum chine beam, and the sheerline in plan is pulled in to give a minimum of flare to the topsides aft.” The waterline L/B ratio is 5:1 and follows the low-resistance design rules defined by Farmer. Although the planked hull was heavy, Puxe could comfortably cruise at 12 knots, with a top speed of about 14 knots, with only a 10-hp motor. She threw up very little wake and Jones estimated that he got 40 mpg at cruising speeds. Today, a quiet 6-kW Torqeedo or ePropulsion outboard could easily do the same job.

While Jones never got around to drawing Puxe for modern stitch-and-glue plywood construction, plans – and even a kit – for a slippery, easy-to-build Chesapeake deadrise skiff are now available. Like Bolger and Jones, Doug Hylan’s “Point Comfort 18” is also designed to carry the heavier 4-stroke outboards. It weighs only 350 pounds, doesn’t need to swell up like Jones’ Puxe, and can be easily trailered. And even though it’s not quite as slender, it can still zip along at 12 knots with a 10-hp motor (see WoodenBoats Small Boats Annual 2014). Hylan stretched his skiff’s waterline to produce the “Point Comfort 23,” and then built Auk, an “optimized” PC23 hull powered by a 10-kW Torqeedo outboard and a bank of lithium-ion batteries. The topsides are highly flared, increasing the L/B ratio to around 4:1. The reported top speed is 14 knots, well above its theoretical hull speed; and the range is about 35 miles (5 mph in calm water) or seven hours with the motor drawing about 1.4 kW of power (that is, only 3 to 5 hp, depending on the specific power conversion ratio used). The optional T-top or small cuddy could handle at least 500 watts of solar modules, which would significantly increase that cruising range on a sunny day.

Finally, consider Ross Lillistone’s 26-foot “Three Brothers,” a power cruiser entered in WoodenBoat/Professional Boatbuilder’s Design Challenge II, which required overnight accommodations and low energy consumption. Three Brothers has a hard dodger, a cuddy big enough for 22-inch wide bunks, sitting headroom, and standing headroom at the helm. Its panga-like bow has a very fine, low-resistance entry – advocated by both Farmer and Jones – for “smooth running in a short, steep chop.” Lillistone, who also drew the well-known “First Mate,” the sailing skiff “Flint” and the outboard-powered “Fleet,” drew an incredibly strong, light, and stiff “egg crate” framed hull. With a L/B ratio of 4:1, he calculates that Three Brothers is capable of over 19 knots with a rather modest 30-hp outboard. A 10-kW electric outboard would be a good alternative, but even a 6-kW motor should be able to drive Three Brothers at over 10 knots in good conditions. Although designed over a decade ago, Lillistone is not aware that his design has ever been built. But it does look like another excellent solar cruiser with plenty of load capacity for batteries and solar panels. Plans are available from Duckworks BBS.

To Look Deeper

This past July the American Boat & Yacht Council (ABYC) approved and published “E-13 Lithium Ion Batteries,” the ABYC standard that now covers the installation and use of Li-ion batteries on boats. Ben Stein, editor of the marine electronics website Panbo, has provided a good summary of what’s in E-13.

For details on Nigel Irens’ slippery power launch “Greta” and his other LDL designs, see “Motorboats of the Future” by Nic Compton in Woodenboat No. 242, Jan/Feb 2015. More about Irens and his design philosophy in Professional Boatbuilder No. 63, Feb/Mar 2000 ("Nigel Irens"). Info on his electric launch “Elektra” is at Patterson Boat Works and at Entropia.

Find more on Kees Prins and building Skimmer, the electric-powered “Rescue Minor,” on his “Fetch Across America” blog.

Plans for Phil Bolger’s boats are hopefully still available from Susanne Altenburger at Phil Bolger & Friends, Inc. Mystic Seaport was recently entrusted with the Atkin’s models, books, and design materials and expects to continue with sales of the Atkin’s boat plans.

Doug Hylan’s boat designs, plans, and kits are at dhylanboats.com. Paul Gartside’s design philosophy and plans can be found at gartsideboats.com.

Ross Lillistone “virtually assembled” his “Three Brothers” cruising skiff on his blog. •SCA•

Long, skinny, slippery hulls - like a multihull sailboat? I've been camp cruising a tiny Windrider 16 trimaran with solar-electric auxiliary for two summers. For fair weather cruising in company with other small sailboats (i.e. Scamp, Siren), it's great. I added solid decks over the trampolines, to support solar panels, and/or a small tent. Because the hulls are so easily driven, I can cruise at 2-3 knots using solar alone, or up to 4.5 knots drawing the max 480W from the battery and panels. Or 7-8 knots sailing (and charging) in ideal conditions. I've managed to put several hundred miles under the hulls without running out of charge.

I'm still waiting for someone to market a simple 10-15lb electric outboard using commonly available Li-on batteries like DeWalt, or Milwaukee. Carry a couple of batteries for weekend "messing about" and use the same batteries during the work week with your tools. The "motor head" of such an outboard would be very inexpensive. Thanks for this article. Electric boats are coming along...but not quite yet I believe. I guess that was also said about electric cars circa 1910!