Small-Boat Anchoring Techniques

by Terry Johnson with illustrations by Stu Whitcomb

[Archives]

One sunny evening last summer I dropped the hook of my 24-footer behind Protection Point at the mouth of Nushagak Bay. The point afforded protection from the SW breeze, but a strong flood tide swept up the coastline, and as soon as the anchor grabbed, the anchor line went bar-tight. As pleasant a night as you can get in these parts, I knew there was only one thing that could interrupt the serenity: in a few hours that tide would reverse and with it the current. But I wasn’t concerned; the little Bruce anchor knockoff had demonstrated its ability to pivot and reset itself. After a long and stressful passage I was exhausted, so I hit the rack and soon was sawing logs.

In the middle of the night—and by late July there is a night even at this latitude—I awoke to an unfamiliar grinding sound. I glanced out the window to see the dark line of shore silhouetted against the sky where I expected it to be, and I immediately slumped back into a deep sleep. The second time I woke to the same sound I got up and checked the plotter. At first I couldn’t understand what I saw on the screen. Then I got it—the curser had me almost two miles from the point where I had anchored, and I was riding a brisk ebb toward the Bering Sea making two knots. The noise, transmitted up chain and rope, was the anchor plowing a groove in the sandy bottom.

I’ve anchored thousands of times over the last 35 years, and could count on my fingers and toes the number of times I’ve dragged, but this episode reminded me never to take anchoring for granted.

A vessel’s ground tackle is a critical piece of its safety gear, the nearshore boater’s parking brake that keeps a boat with dead engine or unfavorable wind from blowing onto a lee shore. It’s also the tool that assures restful nights and relaxing breaks. Every boat needs to be properly equipped, including skiffs and daysailers, and every skipper and crew must know and practice its use.

Countless volumes have been published on anchors, their designs, limitations, and which is “best.” But simply put, the best anchor is the one that is firmly set in the bottom in a suitable location, securely connected to the boat with appropriate rode and adequate scope. Successful anchoring has been described as 20 percent the anchor and 80 percent the technique.

The anchor and gear must:

• Be ready at all times

• Deploy and set quickly

• Hold securely

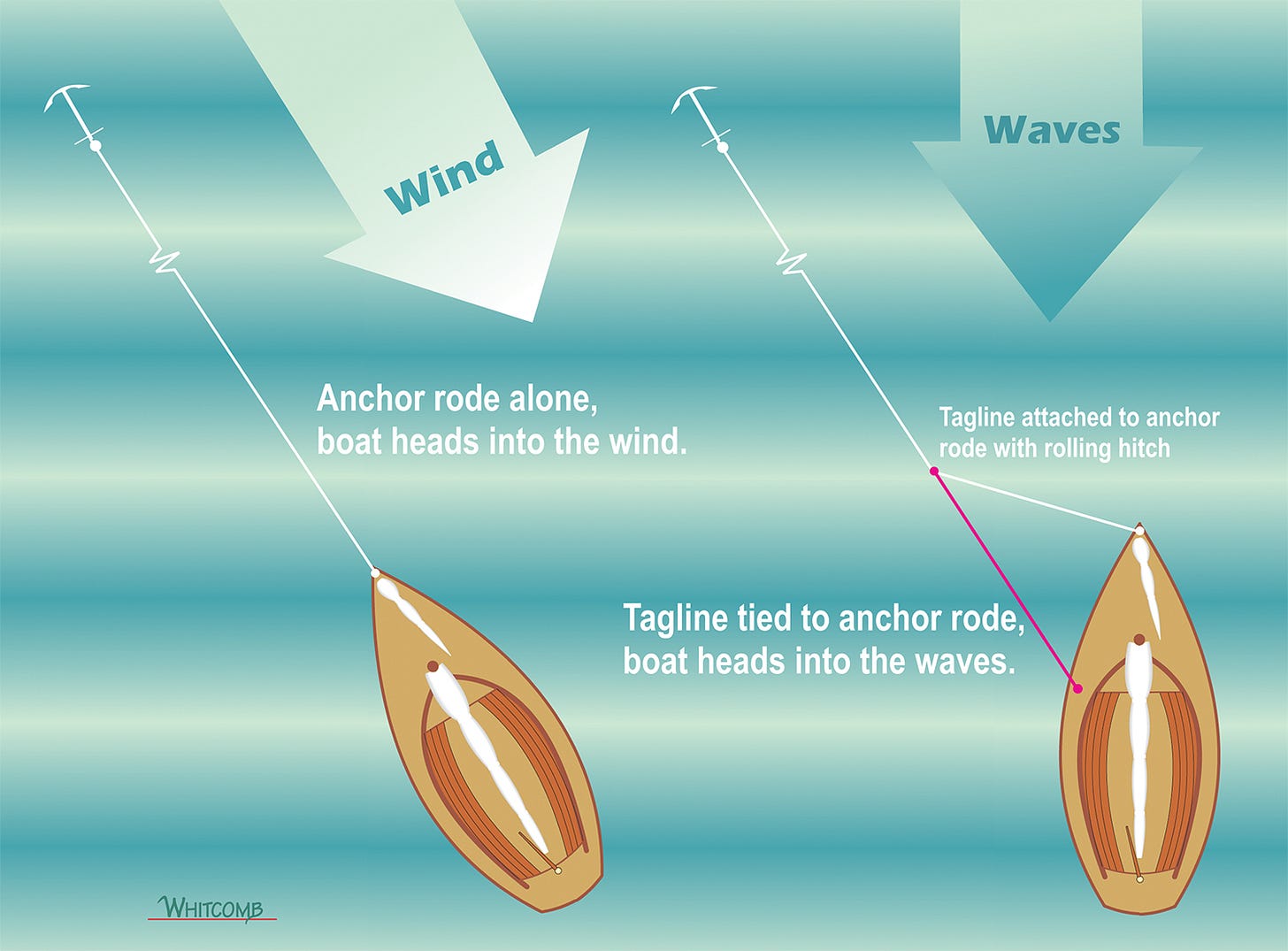

• Remain set or re-set itself as wind and current change

• Release its grip and be retrieved easily

• Be safe and convenient to handle and stow on board.

The English word “anchor” is derived from an old Greek word for “hook” and therein lies an essential concept. An anchor holds a boat by hooking the bottom. A small, lightweight anchor will hold a large boat in adverse conditions if it is hooked securely. A heavy anchor will drag in even moderate conditions if it is not. Anchor design and anchoring technique are more important than anchor weight.

A quick refresher here on terminology: “ground tackle” is everything between the ocean bottom and the attachment point on the boat, including the anchor, shackle (or swivel), chain, and rope. Most small boats use a rode of moderate-stretch, negatively-buoyant rope such as nylon, shackled or spliced to a shot of chain; the two together comprise the “rode.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Small Craft Advisor to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.