Article by by Jacob Stoesz

This adventure, like many good ones, began with a last-minute change of plans. The expected 11-day, mid-October window with no work and no kids was an opportunity that demanded bold action. (While I’m a husband and father of two small children—my wild days seemingly behind me—every so often I act out foolishly.)

The advance plan was simply to put in on the Mississippi River near St. Paul, Minnesota, and see how far downriver I could get sailing, rowing and occasionally lowering the mast for low bridges.

The morning of expected launch, the forecast called for highs in the 30s, rain for the entire week and the river at flood stage. How does an 18-hour drive to Utah’s Lake Powell sound?

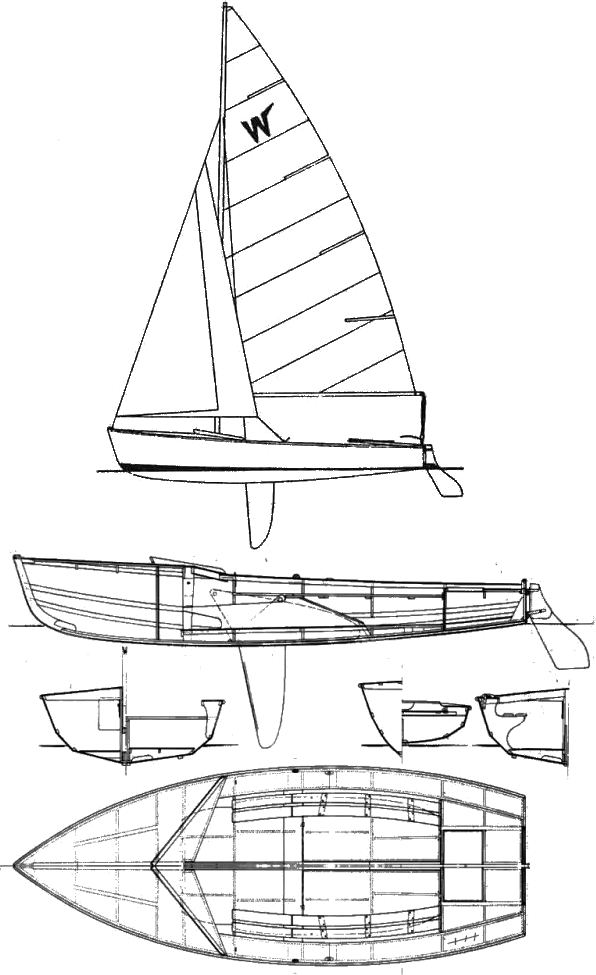

I picked up my pristine, avocado-green Wayfarer, SN 3481—last registered in the 1990s—earlier in the fall. I had only sailed it once prior to the trip, but everything seemed to be in order, if a bit crude in rigging and baggy in the sails. I quickly made a pair of 10-foot oars, stitched up a canvas boat tent and stowed all my backpacking gear aboard. The boat was packed and I merely made a right turn for Utah instead of driving the few miles to St. Paul.

Southwest Utah is a special place to me. The unexpected beauty, the isolation, the Mars-like terrain is in stark contrast to my home state’s boreal forest. I’ve spent considerable time there and I love it dearly. Like a bear trap grabbing your leg, the desert hides its majesty and adventure until you are right upon it.

I put in a day-and-a-half later to windless inky water and a perfect sunny sky. I like rowing, I told myself, and I was off. The first strokes on the water were the first I have ever put into the boat. New oars, new locks, new sockets…it all seemed pretty good.

Putting in at Bullfrog Marina, I was a bit concerned that every shore on the lake was a potential lee shore, adorned with sheer walls extending to the bottom hundreds of feet below. I guess that is what happens when you flood a slot canyon formed by the Colorado river. It hadn’t really dawned on me until the first day on the water that there was no escape hatch. No amount of rode would catch the bottom, even feet from the walls. If I flipped or became out of control—if the wind piped up or shifted—I might be battered to bits on the walls. No climbing out.

But never mind, it was windless and predicted to persist. If the wind came up as it can frightfully do in the desert, I had the time to wait it out, tucked away securely, I told myself.

Three days of solo rowing south down the lake would appear unpleasant to most, but I quite enjoyed it. Self-flagellation has its place in mental health, especially in my season. Unrivaled scenery, perfect sunny days and a constant gnawing desire to know what was around the next bend kept me happy in my new rowing life on the water.

I settled into a pleasant, unhurried rhythm. Rowing all day pulled me ever farther from my car, until I reached the Escalante, Powell’s Cathedral in the Desert…my favorite part of Utah. All around, canyon walls undulate into deep alcoves, slot canyons, slick rock, petrified dunes and little nooks promising to reveal hidden, unmarked Puebloan houses and ruins. The challenge was deciding where to stop—not just because there is so much to discover, but where you could physically pull ashore. Hoping it would help, I’d picked up a valuable, although quirky tome called a Boater’s Guide to Lake Powell by Michael R. Kelsey. I would have been sunk without it. If you are headed to southwest Utah, all of Kelsey’s books on the area are worth reading.

I found some of the best camping of my entire trip, and of my life, up the slot canyons that sinew off the Escalante. One night I camped beside a giant arch on a perfect sand beach under an alcove stuffed in a slot canyon. It was unquestionably the finest place I have ever been in a sailboat.

In this environment, tying off is often done by backing onto the shore and running 150-foot lines at angles off the bow towards buried anchors or boulders on shore. Even the beaches drop off quickly and the silt under the surface is too fine to hold much if a gale blows. A large beach roller under the stern keeps the gelcoat fresh.

For four days I maneuvered my little boat up slot canyons only wide enough to scull, sometimes afraid I might de-rig the mast on the overhanging walls. I hiked farther after the water ran out, up the narrow slots into the desert oases. All these canyons contained more unmarked ruins and petroglyphs, more alcoves, more arches. They were all blindingly lush, green with running water still this late into the fall. I had all walks to myself, stumbling upon shoulder-wide slot canyons, countless waterfalls, unmarked Pueblo ruins, lush grass flats, and arches all untouched and inaccessible to the lake’s houseboaters.

I found it easy to imagine and envy the preindustrial lives of natives who lived in these desert cathedrals. The Southwest is at its best in the fall. The tourists have all gone home; temps are refreshing at night, and it is still t-shirt weather in the day. Powell is all about the hiking and exploring.

On Day Seven, I decided to start heading back, concerned about a forecast of headwinds. Retracing my path, the first day brought real wind—but fortunately, from astern. What fun…and how novel after the previous week of rowing.

But as I discovered, Lake Powell’s narrow canyon walls do not make for a great sailing lake, at least this far north of the dam. Even a tailwind has the most ferocious gusts and shifts. Puffs come down 20 mph above the average and often from opposite directions. Convection-generated up-canyon winds spar fiercely with prevailing winds that are often crosswise to the canyon blasts. Because sailing courses must follow the meanders of the lake, a tailwind may become a headwind as you round a point. Jib-only sailing was called for often, with frequent reefs and changes to the main, but excellent progress was made.

When rowing, I was good for 15 miles a day without too much exertion. But sailing was a significant improvement, although frustrating with my crude rigging. I decided to eat dinner aboard to make further ground with the wind direction, and find a spot described in the guidebook by dusk. This was foolish, for as dusk approached, the hoped-for anchorage was flooded by the variable lake levels and no safety could be found.

Never mind—the wind had dropped and was forecast to be calm. I decided to simply row to another spot some five miles farther along. As the sun went down, my usually constant lunar companion decided to wake an hour later, and soon I was unable to make out my hand from my tiller. Compounding the unexpected blackness, the wind tricked NOAA, and decided to angrily build into the mid 20s, with higher gusts. I put on my PFD and tied it to the thwart… psychological protection at best. All I had now were the channel markers every mile or so, blinking slowly and uncertainly. I could only plot a course from one beacon to the next, carefully keeping to the line for fear of running into an unseen desert wall, perpetually sweeping my eyes for the intermittent faint light.

I was making over 5 knots under bare poles in the pitch black. When the wind aligned with the meander, I could sit on the floor and steer the little boat surfing down into the troughs. But if it was crosswise, the little boat bucked wildly, catching crabs as I madly tried to row along an invisible line. All of this was happening under a multicolored, twinkling sky. I now know why spacemen are called astronauts. I was elated and fearful, alone, sailing across the cosmos.

I rationalized my predicament, holding to the notion that I could tie onto a channel marker if things worsened. It would be unpleasant, wet and wild in the large chop, but the boat would not flip. That is, if I could manage to catch a marker. Frank Dye didn’t have channel markers in the North Sea after all.

At 2 a.m. the wind started to drop and the moon was out clear and strong. I finally made for safe harbor just a few miles from my launch, over 50 miles on the day. I found some thin reeds sticking up from a submerged beach indicating the shallow water. I was able to get out and pull the boat up a slick rock slope on inflatable rollers. I was safe and secure, and hadn’t been off my boat in 18 hours.

When I awoke at 9 the next morning, the gale had filled back in. I was tired, grateful and wild-eyed from one of the most peaceful, scary, majestic, lonely days in years. To be out alone in the desert with only the milky way and your fate to consider…what more could you ask for in an adventure?

As the sun was setting and the wind died, I sailed the last bit for home. I took out, my hands full of blisters, my butt bones calloused from the grind, and hugely satisfied.

If you want stress-free beauty, go. But I urge you to take the outboard. All my stress could have been avoided with an iron sail. If you want a pure adventure, take long oars and some padded shorts. The walls are constant and the harbors are distant.

Either way, Lake Powell is unlike any other body of water in America. Who knows where this small avocado-colored boat will take me next. Maybe Nipigon Bay in Ontario? •SCA• First appeared in issue #125

A mechanical engineer from Minneapolis and father of two ridiculous babies, Jacob learned to sail on Wisconsin lakes on a flat-bottomed scow. His first home after college was a Catalina 34. Getting it out of the slip for the first time was a formative experience.

Great writing and adventure--glad you're safe!

We have sailed, rowed, paddled, and occasionally motored Lake Powell many times. It is one of our favorites as well. Thanks for taking us back with this wonderful story, Jacob.