Sailing to the Rough

Article by Bob Burgess

The first time I sailed to the rough was along the Florida Panhandle. I had never done it before but when I felt my Hobie Cat lock onto a comber and go into her high speed surfing gait I knew we were sizzling straight for dry land come hell or high water. It was just one big swish, bang-bang as the rudder blades popped up and then we skimmed swiftly from the water to high and dry onto a Gulf of Mexico beach.

Swish-sizzle-bam and it was all over! We stepped off onto one of Panama City, Florida’s sugar white beaches as several bathers raced our way, certain that they had just witnessed a shipwreck.

“Hey! Are you guys alright?”

“Yup. Thanks. We did it on purpose.”

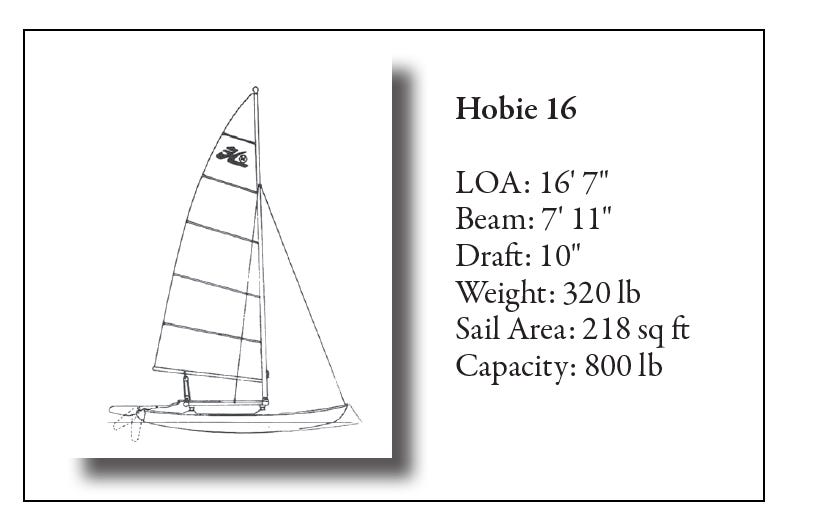

“Wow,” was all they said, looking over our 16-foot Hobie Cat expecting to see at least one thing broken. But there was nothing to see. Hobie Alter had designed this beauty to fly through the waves and to skim up onto any sandy beach Polynesian style whenever you felt like it. No wallowing through the surf with this baby. She just hissed through and went straight in full tilt like one of the waves.

Few boats are purposely designed to sail up onto a beach. When I learned how easy it was I thought if she could go onto the beach then why not enjoy this marvelous invention as both a land and a sea yacht? Why sail back to a launching ramp and haul the boat out to trailer home when you could sail up onto any low-lying beach, sleep there under a simple boom tent aboard your boat, and sail several more days of coastal exploration wherever you wanted?

I liked that idea. I liked it the first time I set eyes on a Hobie Cat. I saw one disassembled and strapped atop a VW van as two sailors drove onto the beach at Guaymas, Mexico where my wife and I were camped in our own VW camper.

These guys offloaded the components of their catamaran and put them all together there on the beach. Next thing I knew they waved goodbye as they took off to explore and sail/camp their way down the Bay of California. Later I learned that they covered 120 miles doing that. I thought, What a way to go!

But what impressed me more than anything was noticing that all the frames, posts and spars of that boat were drop-shaped for streamlined high-speed action. The tramp-framed deck even arced in a curve between her hulls. It was a wing! The faster she went, the more she lifted off the water and tried to fly. Whoever designed that craft got my instant respect.

Back in Florida I couldn’t wait to get my hands on one of those fast cats. I wrote a fan letter to her creator, California surfer Hobie Alter, telling him what I thought about his ingenuity and how badly I wanted one of his cats. I explained that I was a freelance writer/photographer. How could I buy one of his cats? Hobie Alter wrote back that the following spring he had an up-coming Hobie 14 regatta at Apollo Beach near Tampa. He would bring me a Hobie 16 that would be waiting for me on the beach there. So on my November 30 birthday, I sent a check for $1,506 to the Hobie Cat manufacturer Coastal Catamaran in San Juan Capistrano, California. It was 1971. Hobie asked if I would be his guest for a week to photograph his Tampa Bay regatta for him. What he particularly wanted was the compression effect a 400mm lens gives a fleet of sails. I told him I would be honored.

The regatta was a week of fun. I shot a lot of photos from some strange places, including atop channel markers covered with seagull droppings for a bird’s eye view of the racers. I photographed what he wanted and in turn after the regatta he sailed me out on Tampa Bay and showed me how to handle the 16-foot cat with powder blue decks that I later named Kat Baloo.

Today, 44 years later I no longer step the mast by myself. But when I can get help lifting that 26-foot 6-inch spar in place I still sail Kat Baloo at 87.

At my age however I soon learned that changes had to be made. For instance cat sailors are constantly changing sides every time the boat tacks. A lot of kneeling is involved. In my younger years that was no problem, but after my double knee replacements three years ago I was told to forget about kneeling. It is too painful. I may look like a giraffe getting up off the ground but I avoid kneeling. I became fairly adept handling the rudders and tiller and mainsheet from port to starboard by crabbing from one side to the other but it was often scary. Knee-pads solved the problem instantly. They made it comfortable to kneel again. A pair went aboard each of my other three sailboats. My cat also got a telescoping tiller so I wasn’t getting the original 6-foot one jammed into our stack of beach supercargo.

Where there is a will there is always a way. I love to sail. When infirmities of old age got in the way I have so-far managed to get around them. In the process one learns a lot of small dos and don’ts and simpler ways of doing things. That’s what this is about.

Last year reader Rock Tabor e-mailed me that he had read some of my sailing articles and was interested in sail/camping aboard a catamaran. He had sawed his way through a forest of bamboo to liberate an old Hobie 16 he bought and was restoring for his family use. Appropriately the name be gave it was Cat Bamboo.

I suggested that Rock join me aboard my cat to see how it was done. This was not to be a sailing lesson, it was more about making a live-aboard out of a boat never really intended as one.

Rock agreed and we trailered Kat Baloo down to the Gulf of Mexico for several days of bay sailing. The Florida Peninsula is ringed with sand barrier islands. Some natural; others resulting from dredged channels. Most have been around long enough to have pines, palm trees and low-growing shrubbery on them. Some islands are linked by bridges to the mainland and have State Parks on them. Other islands are owned by the state but are not yet linked to the mainland by bridges. All of them are pristine and accessible to boaters who like getting away from the mainland crowds to enjoy these natural island beaches.

Years ago when I first experimented with the idea of the Hobie being a land/sea sailboat, a friend and I used long sheets of plastic to push the boat ashore, then slept under the trampoline deck on inflatable mattresses. To keep out mosquitoes we wrapped mosquito netting around our enclosure, clothes-pinning it to the overhead tramp. All of which proved unnecessary since the sea breeze kept away the insects and the flexible vinyl-coated nylon deck of the cat was softer than the ground. After that we did away with the inflatable mattresses and moved topside under an easily erected boom tent.

One necessary item for boats without a topping lift, such as the Hobie, is a short 12-inch cotton line extension tied onto the end of the main halyard. At the end of this extension you tie a simple overhand knot. It fits into the aft end of the boom’s sail groove so that tightening the halyard lifts the boom to the desired height for the boom tent.

Any size plastic tarp approaching an 8x10-foot size works fine for your tent. You can change the height of the boom to fit what you use. Be sure the sides overlap the edge of the deck frame so rain will run off rather than into the enclosure.

I also carry a 9 x 14-foot tarp that can do double-duty as a large waterproof bag for all our camp gear. The tarp goes first on the boat’s deck, then everything is placed atop it and the sides are gathered up and tied together to form a waterproof bag for everything. But this too became unnecessary as we learned to pack tightly in smaller waterproof bags that we tied to the trampoline’s lacing. Our bedding of a pillow and a sheet apiece went into the bottom of our bags. On cooler nights we just dressed warmer. More recently I switched the sheet for a tan summertime lightweight Snugpac Jungle Bag from Amazon that is perfect. All camera gear, cell phones, solar-charged power pack, VHF radio and other electronics with valuables went into a separate smaller waterproof bag that tied to the deck and stayed with us at all times. Now our large tarp serves as a runway for steep shingles and the small tarp serves as the boom tent. Both fold flat compactly.

With Rock aboard we searched for a pleasant barrier island bay beach backed up by sand dunes and picturesque sea oats. Once we found it, the boat’s bows went up onto the shingle; the cat was unloaded and then we both got behind her and pushed her ashore.

Since the beach shingle was steep in the section we selected, we dipped the large tarp in the bay, and placed it in front of the cat to make it easier to push the 300-pounds up that steep shingle and ashore. In this instance she was at least three feet above sea level. Other beaches are often almost at sea level so we just sail in and push the boat well above the tide line.

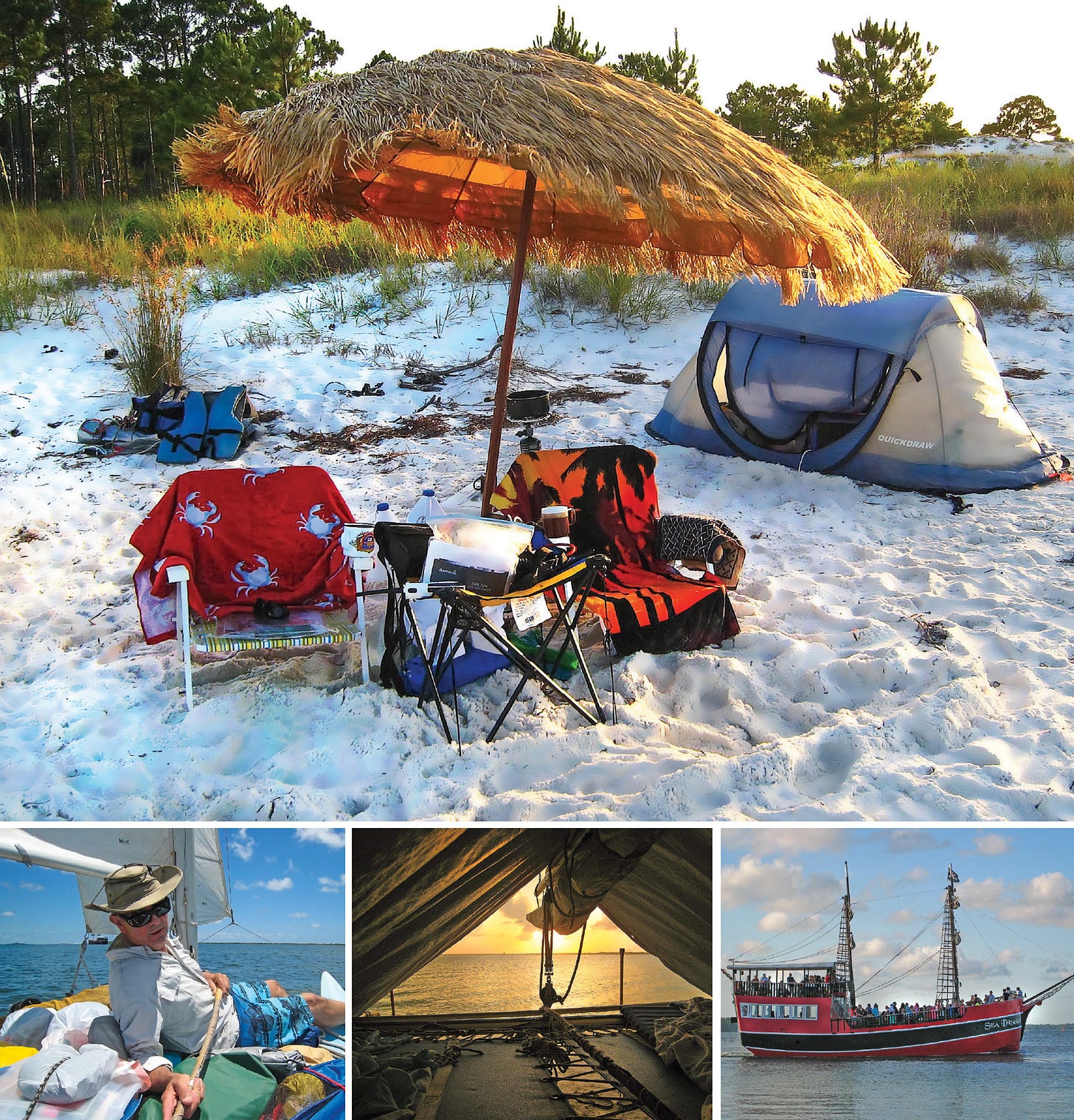

Since good shade is primary, I now use an 8-foot wide thatched tiki umbrella that is not put in a permanent holder, since the umbrella needs to be shifted often from almost horizontal for the morning sun to upright at high noon. These large thatched tiki umbrellas (Google them) have air relief slots near the apex to let strong gusts out before taking the umbrella away. Ours has withstood heavy rainfalls with everything remaining dry underneath. Best of all the thatch makes them look like part of the scenery.

Folding beach chairs and a small folding canvas table are essential. Solid plastic containers with lock-down lids carry our galley of cooking items. Our bottled gas single-burner stove is an always reliable Coleman. One large pan is all we need for making camp coffee, boiling hotdogs in seawater, or for heating cooking oil for frying fish. Forget those gas lighters because the slightest breeze blows them out. We use special waterproof matches that light even when wet. You can find them on the Internet. Larger items go in plastic garbage bags or the Wal-Mart variety for smaller items and trash that we carry back to the mainland. Our dinner plates are unbreakable colorful Frisbees, fine for plate-ware or after-meal beach fun. Perishable food such as hotdogs and pre-made hamburger sandwiches is carried in a foot-square soft-sided insulated cooler with containers of frozen water. Four one-gallon plastic jugs of water are tied at the corner struts below the boat’s deck. All items requiring cool shade go into a small Quickdraw Self-Erecting tent that sits behind our umbrella. A rolled 20-foot seine net is used to catch our high protein fresh fish. One sweep of the net near shore provides more than enough fingerlings for deep-frying. The remainder is returned to the sea.

On this trip with Rock I tested my idea of how one man can work the 20-foot seine by himself. Take one of those auger-type sand drills used to support a beach umbrella and screw it into the beach at the water’s edge. Place one of the tubular aluminum net rods in it. Then one man takes the seine’s other rod and makes a net swing around the beach shallows and comes ashore with his catch.

The mainstay of any beach site is the shade you create. My 8-foot diameter tiki style beach umbrella was more than adequate. Initially I used a screw-down unit that anchors the umbrella. But soon found that it worked better if we dug a hole in the sand with a small garden trowel so that the umbrella could be angled in any position to block the sun’s intensities. Early morning and late afternoon we often angled it so that it almost touched the beach in order to create the long shadow we wanted. As back-up sand anchors I made several 8 x 4 x 1 inch wood anchors with line coming out of their centers. Buried flat a foot under the sand, these make excellent sand anchors for anything that might blow away. The tent had stakes but the gallon water jugs and other gear kept inside anchored it sufficiently.

With northwest Florida’s June temperatures ranging from the high nineties during the day to the mid-seventies at night, if your boat is facing the sea-breeze you may get chilled during the night. We found that additional clothes resolved the issue, but so does turning the boat 90 degrees so that the sea breeze hits the tent’s flank.

Wearing a long-sleeve light colored shirt and wide-brimmed hat is the best way to protect yourself from the sun’s heavy onslaught. Another lesson learned the hard way is to always wear a chin strap when sailing or your chapeau may take wing.

We sailed and enjoyed our pristine island camp for several days. The best of times were when the island boaters who came ashore with their umbrellas and chairs, finally left. Then we had our topical island all to ourselves. And when we finally slid our loaded boat down the plastic ways, all we left behind were footprints. What we took with us were good memories of sailing and camping for days on a pristine piece of tropical paradise.

If your boat isn’t made to sail ashore, just drop anchor off shore and set up your own thatched tiki-topped base of operations ashore. After that you’ll enjoy the best of both worlds. •SCA•

Bob Burgess grew up sailing small boats in Michigan, and later in Florida. From his enjoyment of small boat sailing he wrote Handbook of Trailer Sailing. His adventures both here and abroad resulted in his writing over 20 books on ocean oriented subjects.

First appeared in issue #96

Bob Burgess' book is the reason why I fell in love with small sailboats as a child. I grew up cruising the coast of Maine with my parents on larger keelboats. During one of our summer trips we stopped somewhere along the cruise where there was a bookstore, and I was allowed to pick one book... I ended up with a copy of The Handbook of Trailer Sailing. I was like 10 years old. I wanted a Com-Pac 16 for years and years after that. I eventually got one in my late 20's. Now 40 years later (with a whole slew of boats in between) I'm on my second Com-Pac 19.

Thanks, Bob!

Excellent article. Yes, I once saw a Hobie 16 careen full tilt about 50' onto a grassy public beach. Three young lads spontaneously launched, then rolled another 20' to a dead stop of endless expletives and laughter! 😝😆🤮