[Archives]

There may be many reasons for wanting to cover a boat—long-term storage, protecting varnish, keeping debris from clogging the scuppers and flooding the cockpit, or providing protection for winter construction projects. In our case, our 25-foot 1981 Dufour 1800 sits on a trailer in northwest Oklahoma. For days on end, winds of 40-50 mph cover everything with thick layers of dense, red dirt, even driving it below and into every drawer, locker, and berth. Also, the only place we have to park the trailer and boat is beneath two large pecan trees. In addition to the natural foliage and branch debris from the trees, squirrels litter the deck with scattered pecan shells that dye the fiberglass a deep purple or black. While this can be bleached out, within a day the squirrels will have returned the boat to the same state.

I’ve tried covering the boat with tarps spread over the deck with no success. With a ridge line erected over the boat, I’ve draped tarps over the line with tennis balls hole-sawed and taped atop the stanchions to prevent chafe, but the flogging tarp ripped the balls off and stuck the stanchions through the tarp creating large, jagged holes. If that didn’t happen, large unsupported sections of tarp would pool with rainwater until the sagging belly weighed so much the tarp would finally burst. Seeking a solution in earnest, I scoured the Internet to find winter covers for our size boat. With prices running between $1,000 to $2,000, such an expenditure wasn’t worthy of even a minute’s consideration.

A couple winters ago, however, I volunteered aboard the Kalmar Nyckel, a 17th century square-rigged, four-masted Dutch pinnace that serves as the official flagship for the State of Delaware. It winters on the Christina River in Wilmington, DE. All winter it is covered with a greenhouse plastic tent erected over an elaborate PVC pipe frame. While the crew continues to train on deck and carry out maintenance work, the ship is protected from snow, freezing rain, and strong winds that funnel up the river. If that works on a 200-ton ship, I reasoned that it should certainly work on a 25-foot trailersailer, even in the winds of Oklahoma.

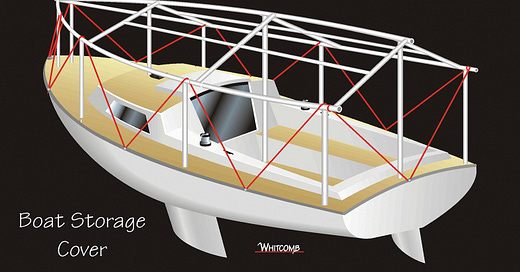

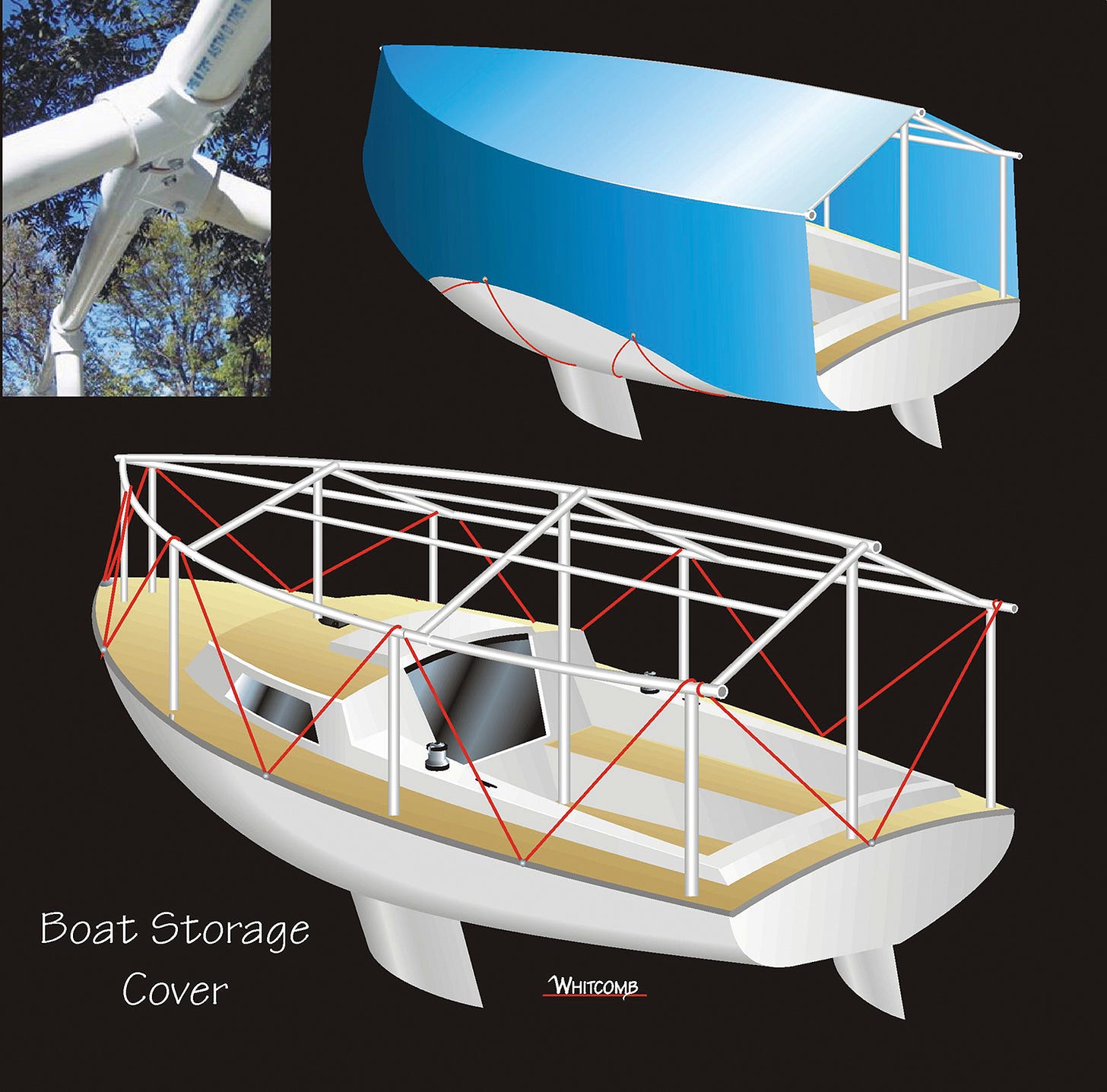

Laying out the design on graph paper enabled me to calculate the amount of materials needed. By measuring the boat’s beam between each pair of stanchions, and the distance between stanchions, and of course the boat’s LOA, I had the skeleton that the rest of the frame could be designed upon. The entire frame is made of 1-inch PVC schedule 40 pipe, and rests upon pipes that run full-length on deck, port and starboard, sandwiched between the stanchions and the toerails. Uprights cable-tied to each stanchion extend several inches above the stanchion tops to join another full-length pipe, called the “plate” in house construction, to which the “rafters” are attached. This height above the deck gave me good crawling clearance along the side decks. The full-length ridge pole has three vertical supports to the deck to help support the weight of snow or freezing rain. The ridge pole gives me 42-inches of clearance over the coachroof and better than full-standing headroom in the cockpit. I was seeking a compromise between reasonable working room on deck while keeping the profile low enough to prevent possibly dangerous windage in frequent cold fronts that easily produce 70 mph winds. When in the water, the boat would just heel and yield to such pressure, but on a blocked trailer, I sought to avoid a worst case scenario of the trailer being toppled off its block piers. Once all the rafters were in place, I cut them at their respective mid-length, and inserted cross-connections that enabled me to run another full-length pipe between the ridge pole and the plate. In conjunction with sufficient pitch to shed rain, this added strength and reduced the square-footage of the tarp sections to prevent pooling of water. The diagram also enabled me to determine the number of tee, elbow, and cross-connectors I needed.

Rather than cementing the pipes and connectors together, I dry-assembled everything with 1/2" No. 8 hex-head self-tapping screws. In this way, if a pipe should break from ice or a fallen tree limb, a section can easily be removed and another slipped into its place. The pipe was flexible enough to follow the sheer of the hull with a couple exceptions. In those cases, two sections of pipe were joined by hose-clamping a short section of reinforced hose between them to provide the needed flexibility.

The entire frame, which should last for many years, cost $187.24. The boat could be completely covered by a one-piece 16 X 26-foot tarp, but having two smaller tarps on hand enabled me to do the job without buying more materials. My granddaughter loves the new tent playhouse, and the cover has already proven its value in keeping the boat clean. By the time of this writing, the frame and cover have been through several weeks with winds over 50 mph with total success. When the boat’s ready to go in the spring, the entire assembly should come off in one piece, or two sections for convenience, and sit on the ground ready for the next winter’s storage.

Tools: tape measure, pencil or fine marker, saber saw, electric drill with hex-head driver, bullet level, 10-inch cable ties, sandpaper to clean cut pipe-ends.•SCA•

James Neal, now a retired sea captain, has sailed and messed about in boats all his life, with a long resume in schooners, delivery, tugs/barges, charter, sailing instructor, and oil field supply vessel captain.

It is not as roomy, but for storage of my Sparrow 16 for the winters in North Idaho where we can get a good amount of snow, I will use the mast as the ridge-pole for the a tarp that I lay over it. But, to make sure the snow doesn't collapse the tarp, I take one of my long lines and weave it back and forth over the mast from the fore to aft end of the cockpit. This has worked quite well.

Excellent design, and very similar to my own evolution. One addition I would suggest: cover the tarp with a light-weight fishing net. I've found that having a net over the tarp greatly extends the life of the tarp. I've also used recycled heavy-duty vinyl (old billboard signs) instead of the typical plastic traps.