by Jerry Montgomery (originally appeared in issue #88)

I was introduced to the Balboa 20 by its designer, Lyle Hess, probably in 1967 or ‘68, when Richard Arthur, owner of Arthur Marine, offered me a boat when the project was finished if I would help Lyle do the tooling. We did the job in about six months of nights and weekends. There is much more interesting history involved here; Richard Arthur was introduced to Lyle by Larry Pardey, who was making a bluewater boat of Lyle’s design (Seraffyn) that he and his wife Lin would circumnavigate in a few years later. Many of you probably have their book, as do I, Cruising in Seraffyn.

Needless to say I learned lots about tooling from working with Lyle, and quadrupled my knowledge about boat design. Richard was true to his word, and Lyle and I both ended up with boats. I sailed mine for a few months and then sold it and used the money to go back to college, which was my intent all along, but Lyle kept his for years. I sailed the boat long enough to learn it pretty well, and much of this knowledge was put to use in later boats, like the Montgomery 17. When I made a “company boat” of one of the first M-17’s obviously Lyle and I challenged each other to a race in Long Beach harbor, where Lyle kept his B 20. I was quite proud to win, solidly if not spectacularly, and Lyle was impressed with the new boat also. There were several things that could be improved on the 20, and we took advantage of them to make the M-17 a better boat, just like the more recent Sage 17 is an improvement over the Montgomery. We like to think we learn from each design.

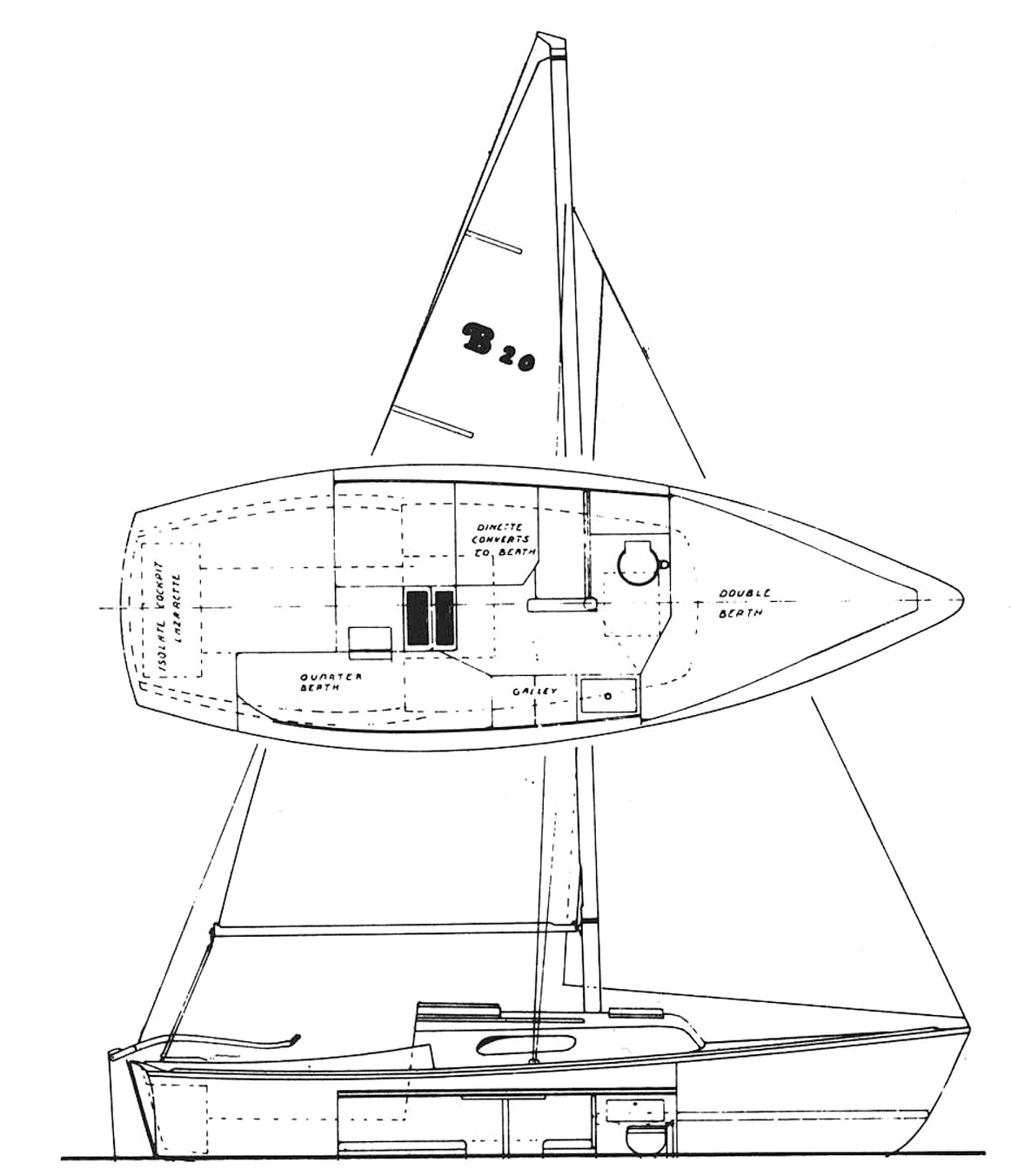

The Balboa 20 has a retractable keel, an iron casting of about 550 pounds, with weight concentrated towards the bottom. This worked pretty well except for a couple of things, the most important of which was that the keel retracted up partly into a trunk, which was an open trough when the keel was down and created quite a bit of turbulence, as did the wire that was used for lifting the keel. The wire needed to be in just the right spot to keep it from humming, and on a well-used boat needed to be replaced occasionally to keep it from breaking at the wrong time. Also, all the weight of the keel was hanging from a pin, probably 1-inch, which is a potential safety problem that needed regular inspection and really liked to leak.

The keel employed a similar principal to other boats of that time, like the Catalina 22 and most of the Ventures. How to improve the keel? The Balboa 20 eventually had an optional fixed fin keel which was a great improvement, both in safety and in performance. I sailed on one, and it was night and day. If I had a 20 and was ambitious enough to want to improve it I’d go with a bulbed daggerboard. Most of the work would be in ripping out everything to do with the original drop keel and making a trunk in the interior. The mechanics would need to be worked out so that the lateral area was in the right place, and I’d definitely go with epoxy resin, which sticks much better on old fiberglass. Using a bulb, which puts most of the weight down low and results in more righting moment, probably a hundred pounds could be eliminated. I’d definitely try to find a factory made daggerboard of about the right size, which would require some research. There are several tricks to making a daggerboard work smoothly, like using nylon or teflon or some sort of plastic sheets, sawn out to be a close fit, as bearings top and bottom. And obviously the whole board/trunk setup needs to be very strong.

A keel/centerboard arrangement would work great, but it’s a lot more work on an old boat. Probably the easiest way would be to make it on the bench out of fairly hi-density foam, shaping it and glassing the outside, hollowing it out and glassing the inside and constructing a trunk for the centerboard, then filling it with the needed quantity of lead, probably at least 600 pounds, then bonding it to the hull. You’d need to make an A-frame big enough to lift it high enough to work on it unless you have a barn. Pure lead weighs just over 700 pounds a cubic foot, but shot weighs only 2/3 that, and that’s with the spaces filled with resin, Wheel weights (cheapest) weigh less than half. So you need to figure out the volume, allowing for the trunk, pretty closely. I’d consider using plywood, well shaped and heavily glassed and with some holes cut out to fill with lead so that it would drop, for the centerboard. But I repeat, on a retro-fit, a bulbed daggerboard would be far easier to do.

The rig on a Balboa 20 is far from perfect. It was a 7/8 rig with a backstay, but for the sake of simplicity a very heavy mast was used in order to eliminate the need for spreaders. In my opinion a lighter mast with lowers and spreaders (probably about 30" long and raked aft to match the path of the shrouds to the chainplates) would have been far better. Easier to set up because of less weight, bendier so that sails could be flattened out in a blow, and less heeling and pitching. I could really feel the weight of the mast out in a blow, especially in rough water. I’d feel comfortable using a mast of about 1.5 lb per foot, like the Dwyer DM 6, if it’s made of 6061 T6 material (which the Dwyer is). If it’s made of 6063, which is about 20% lower in tension strength, you would need to go with heavier material. If money matters and you’re a good scrounger, a discarded Hobie 14 mast might be OK. Look at the Dwyer site and go from there. I don’t remember the length of the Balboa mast but it’s probably about 23 or 24 feet. Also, Dwyer has spreaders and mastheads for all their sections. Mast sections are one of the things I’m picky about on my own boats, and on fractional rigs a “just right” amount of bend is really critical to getting a good sail shape.

The 20 used a terrible roller reefing setup that appeared to be simple, but when used with a bolt rope on the luff of the main it wadded up when reefed and the main picked up an ugly shape. Slab reefing would be much better. Obviously, you need a good vang of about 4 or 6 to one depending on how it’s rigged, a tiller extension, new sails, some paint, and about 5 or 10 years of back-breaking work and you’re ready to go sailing! •SCA•

Thank you Jerry for sharing your wisdom and insight about the keel. I always wondered what it would be like to Bolt a hundred pound strip of weight to the bottom 4 inches of my Potter 19 keel.

I think that since Potter has a hard chine that resist healing over that I wouldn’t notice it.

Concerning lead ballast: wheel weights are no longer made of lead. I learned this when scrounging lead more than 10 years ago. I PAID (fortunately no much) for a bucket of wheel weights, about half of which wouldn't melt no matter how hot we got the crucible! I also learned that Schnitzer's scrap yard no longer bought or sold lead. But you can order lead ingots from Amazon, with free Prime shipping to your door! But I managed to scrounge enough lead for my ballast from friends and acquaintances without getting it from the little bald guy -- who wasn't bald yet back then.

I used the "lost styrofoam" method to cast the lead pigs.