“It is not enough to fight for the land; it is even more important to enjoy it. While you can. While it’s still here. So get out there and hunt and fish and mess around with your friends, ramble out yonder and explore the forests, climb the mountains, bag the peaks, run the rivers, breathe deep of that yet sweet and lucid air, sit quietly for a while and contemplate the precious stillness, the lovely, mysterious, and awesome space. Enjoy yourselves, keep your brain in your head and your head firmly attached to the body, the body active and alive, and I promise you this much; I promise you this one sweet victory over our enemies, over those desk-bound men and women with their hearts in a safe deposit box, and their eyes hypnotized by desk calculators. I promise you this; You will outlive the bastards.” —Edward Abbey

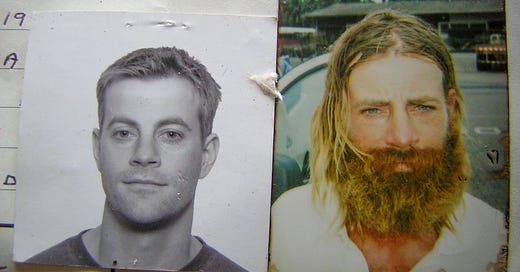

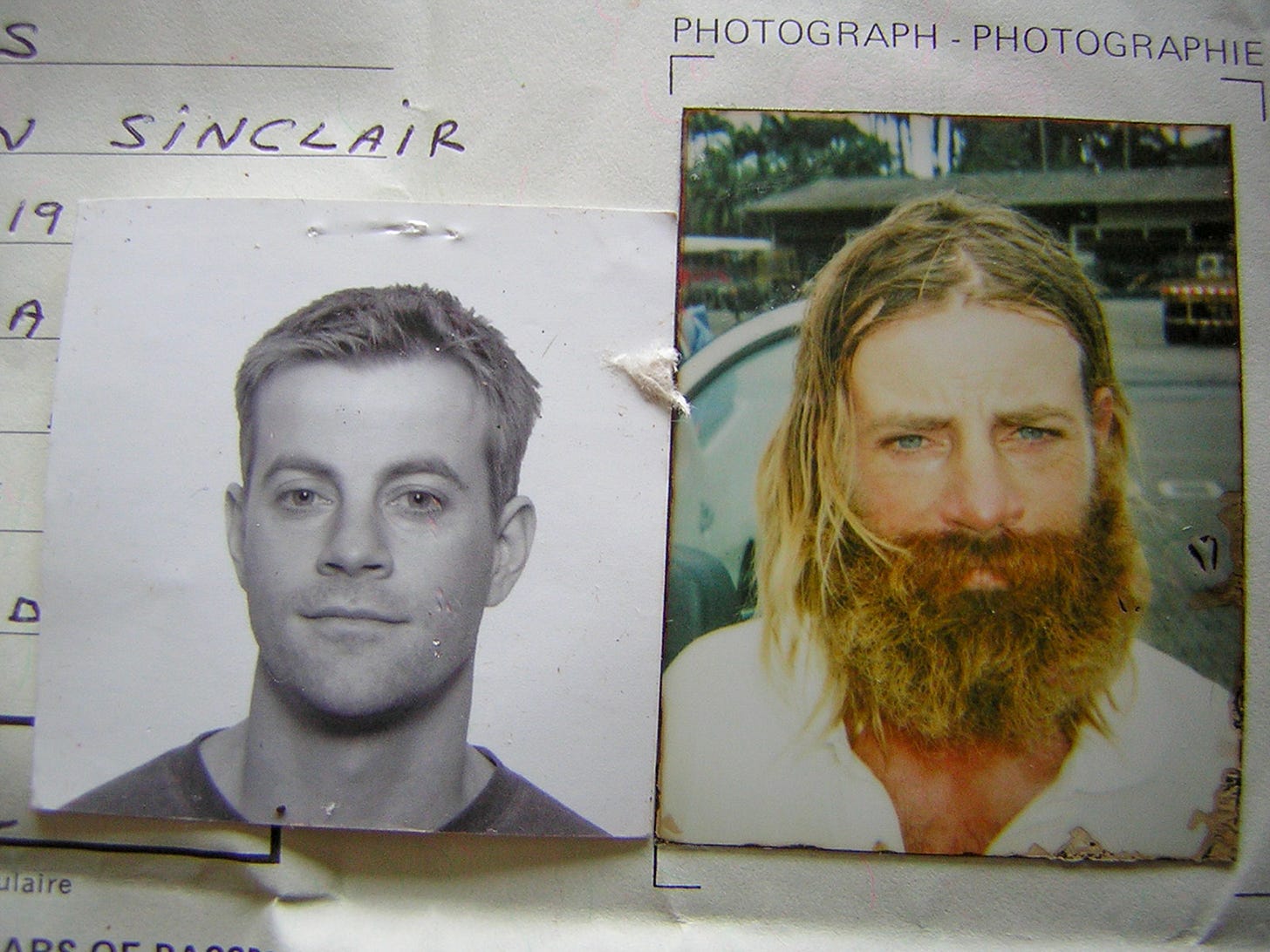

The first thing you notice is that he’s less assuming than you expected. After all this is the same Colin Angus who was shot at by guerrillas during a perilous trip down the length of the Amazon, who broke the human-powered speed record rowing around rugged Vancouver Island, and who survived a first descent of the 3417-mile Yenisey River—where he became separated from his party and spent 12 days alone wandering Mongolia without a shirt, shoes, wallet or passport. Where’s the brash? You wonder. Where’s the flash? Where’s the beard?

“That’s the most disappointing thing for people just meeting me,” he says, “People do expect the beard.”

Instead they get a thoughtful, soft spoken, clean shaven, author, boat-designer, husband, and father. But get him talking about past and potential adventures— bicycling across Siberia, fraught small-boat voyages, or anything else seemingly ill-advised or impossible—and the other Colin bubbles to the surface—the fiercely determined explorer who in 2004 became the first person to circumnavigate the globe under human power, including a row across the Atlantic with his wife and fellow adventurer, Julie Angus. Bother asking Colin “Why?” and he’ll surely respond “Why not?” What follows are a series of interview questions that elicited longer answers.

In almost every endeavor, regardless of how difficult, there is usually someone who has “been there” and can be turned to for counsel. But you guys live right out at the edge; how do you make intelligent decisions about what’s reasonable and what’s insane?

The key is to fully understand what you are getting into and to know what your abilities and limitations are. For example, even though our attempt to row from Europe to North America was a first, there was plenty of information already available on offshore rowing. And skills acquired from being in all kinds of small boats—from kayaks to sailboats—contributed to our knowledge of what we were up against. You need to distill the key components for success and make sure you cater to them. With the row, it came down to three things: the boat needed to be seaworthy, it needed to be efficiently propelled by human power, and we needed systems and supplies to sustain life for five months. That was it. And a whole lot of work of course.

We’ve seen couples exchange harsh words at the dock after a simple day sail. What made you think your relationship could survive rowing across the Atlantic? Did adjustments have to be made in that regard?

The two of us lived together for five months in a rowboat with a cabin about the size of the space under your kitchen table. You can’t go on a five minute walk to blow off steam; instead you’re perpetually staring at your partner. And of course, the expedition itself contributes to stress and frayed nerves. We spent time in advance discussing strategies to reduce friction, and found our tactics worked remarkably effectively. One of the most important things we did was schedule a weekly meeting to discuss our dynamics. It’s much easier bringing up issues or making suggestions when everyone is in a good mood, as opposed to when your partner is eating the last two chocolate chip cookies.

It’s been said that the more ambitious your project, the more negativity and doomsaying you’ll encounter. Did you find this to be true?

Absolutely. I find, though, that the more adventures I do, the less negativity I encounter, however, it was extremely difficult at the beginning. There must be so many great projects and ideas that are never realized because of the naysayers. The key is to understand that naysayers are simply a part of the equation, and it’s not because you don’t have the skills or your project is unsound. You’ll always face some uncertainty, but try to ignore the naysayers and instead focus on preparations and gaining the appropriate skills and knowledge.

Could it be argued that statistically your cycling miles were more dangerous because of your proximity to motor vehicles, or perhaps more unfriendly people, than those on the open ocean?

Definitely. We’ve traveled along countless busy highways, with large transport trucks passing inches from our bikes. The thing is, on highways you don’t get the dramatic close calls. For example when you’re on the ocean and you get hit by a hurricane, you can spend hours regaling stories of the fear and drama. On the highway, though, you either get splatted or you don’t, and there’s not much of an in-between. I do feel, however, this is where the greatest danger was.

It would seem that traveling under pedal-power would entail less boredom than rowing, if for no other reason than the constantly changing landscape. How do long-distance rowing and cycling compare in terms of tedium, hardship, and physical challenges?

Generally, cycling offers much more stimulation; you have frequent encounters with people, and constantly changing landscapes. It’s also easier psychologically—you don’t have the continual unease that you often feel on the ocean.

What’s new at Colin and Julie’s company Angus Rowboats? Their Wheelbarrow Dinghy for one thing. A stitch-&-glue pram offered as plans or complete CNC kit.

What do you think the average person’s biggest misconception might be about the realities of rowing across an ocean? We suspect it might be similar to what some people say about police work—hours of boredom, interspersed with moments of terror. Are we close?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Small Craft Advisor to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.