Floating Homesteads

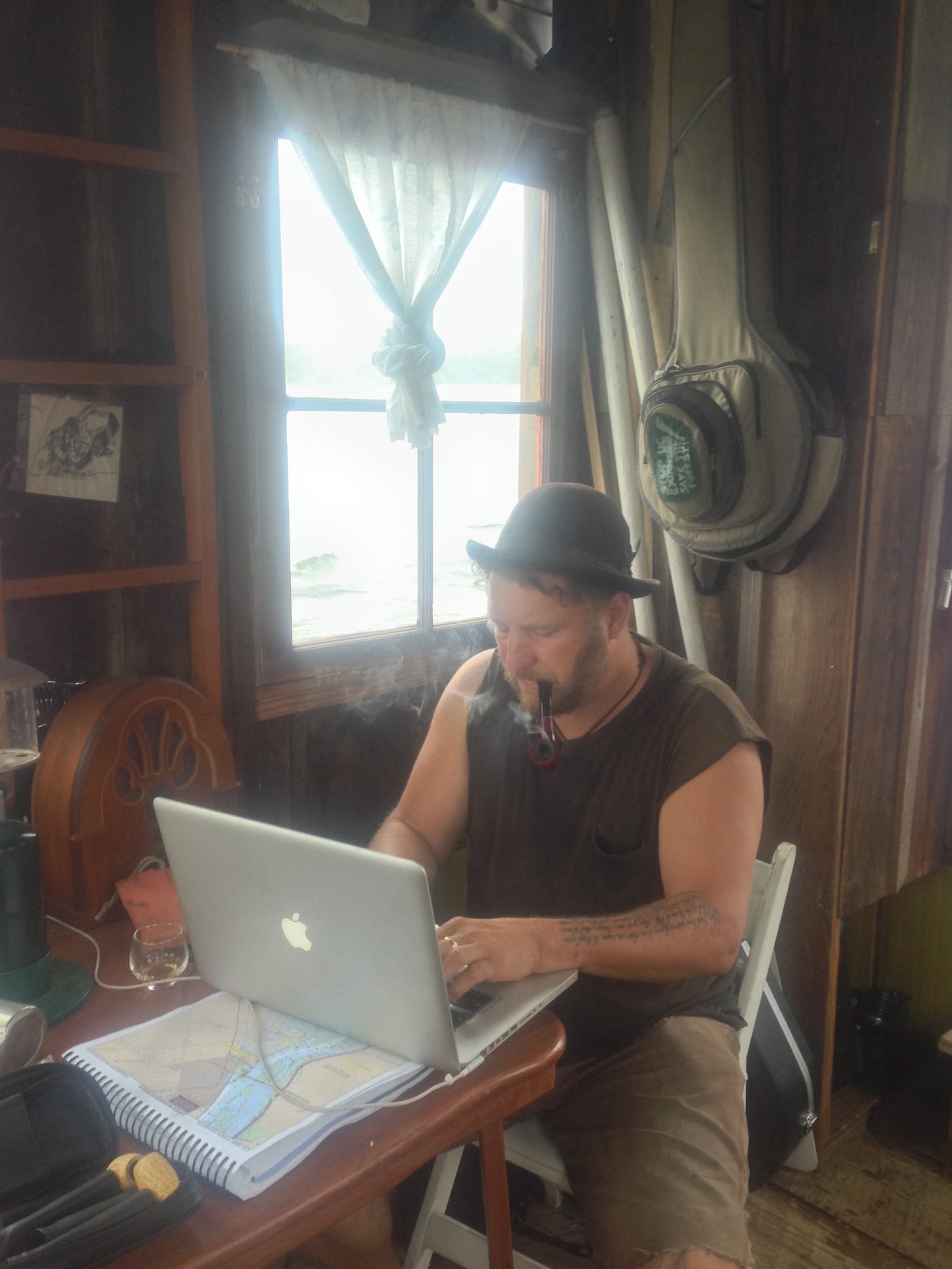

Our Interview with Wes Modes about The Secret History of American River People

Author Harlan Hubbard’s definition of a shantyboat:

“A shantyboat is a scow with a small house on it. Nearly always a homemade job, it is put together with odd scraps of material and pieces of driftwood and wreckage. Yet it is more than a floating homestead: it is an ark which the river bears toward a warmer climate, better fishing grounds, and more plentiful and easier work on shore. At one place after another the hopeful boatman lays over for a spell, until disillusioned, he lets his craft be caught up by the river’s current, to be carried like the driftwood, farther downstream. At last he beaches out for good, somewhere in the south, where his children pass for natives.”

Anyone interested in shantyboats or river living will want to explore Wes Modes’, A Secret History of American River People. Wes’s pioneering social practice work with the people who live in American river communities has been nationally recognized and reported worldwide. A Secret History of American River People combines social practice, oral history, video, photography, sculpture, new media, and adventurous fieldwork on American rivers since 2014. It’s a trove of interesting and informative posts, stories, videos and images.

What follows is my interview with Wes. —Josh Colvin

Tell us a bit about The Secret History of American River People project.

A Secret History of American River People is a project to build a collection of personal stories of people who live and work on the river from the deck of a recreated mid-century shantyboat over a series of epic river voyages. The project engages people living in contemporary river communities in dialog, examining the personal stories of ordinary river people and the ways that river communities respond to threats to river culture such as economic displacement, gentrification, environmental degradation, and the effects of global climate change.

How much time have you spent on rivers (and on which rivers) exploring and living aboard?

We’ve spend nearly every summer since 2014 on a major American River, including the Upper Mississippi, the Tennessee, the Sacramento, the Hudson, and the Ohio. In our ninth year of the project, the Shantyboat Dotty has traveled 2500 river miles, and 25,000 miles by highway. We’ve conducted 175 oral history interviews and talked to thousands of people about the river.

I did a 150-mile trip on the Columbia some years ago and was surprised to come across a few folks living aboard in remote sloughs and backwaters. Are there still a lot of people living on rivers across the country?

Up until the mid-20th century, there were tens of thousands of families living in houseboats, shantyboats, and cabinboats on inland waterways across the U.S. Virtually every town on a lake or a river had at least one houseboat community. Now these communities are largely extinct.

That said, there are still a few pockets of liveaboards here and there. In a few towns on the Upper Mississippi, boathouses were converted to livable spaces and then grandfathered in as other shantyboat communities were pushed off the river. Here and there on the West Coast, there are scant remains of large communities of floating houses near San Francisco, Portland, Seattle, and a few other places. A few river and bay towns have small squatter communities of liveaboards that were sometimes at odds with local regulations—places like New York City, the Sacramento Delta, Tampa, and Key West. And naturally, every marina has a few people who live aboard at least part of the year whether allowed to or not.

How is living aboard treated in terms of laws and regulations? We assume some rivers are more “shantyboat-friendly” than others? Which river or region has the richest shantyboat culture presently?

Laws regulating liveaboards are local and regional. For instance, the limit to how long someone can live in their boat in one location varies from state to state and even from city to city. In some places, there is no limit, while in others, there may be a limit of 30 days, 60 days, or even 90 days.

In our case, at most we stay for a few days in each town, often in the local municipal marina, so we seldom run afoul of local laws. However, occasionally a DNR officer has stopped by to remind us that we can only camp on a riverbank for so many days.

Which areas or rivers are more shantyboat-friendly? Well, we found that where there is money, there are rules. The wealthier the community, the more likely there is enforcement of ordinances to prevent water squatters.

What has changed about river life, and what has remained the same?

From our interviewees, certain themes emerge about the changing conditions along the contested river's edge and how that has impacted their communities' racial and economic demographics. Where historically the land adjacent to polluted rivers was a place where poor and itinerant people were forced to live, in the 1970s, the Clean Water Act increased the desirability of riverside real estate. Since then, American rivers have sprouted expensive marinas, expansive homes, and grassy parks. Economic displacement along river corridors is a real and growing phenomenon.

Have you noticed a surge in shantyboats on the water or interest in them generally?

When I started building the Shantyboat Dotty ten years ago, I could find few references to people building such crafts beyond archival materials from brief houseboat fads in the early 20th century. As we’ve traveled the country over a decade, we’ve met scores of mostly retired men working toward living out their shantyboat dreams.

What history are you concerned is being lost or needs to be documented?

The seeds of the project were planted during my travels on American rivers since 2004 and observations that river culture was endangered by displacement, gentrification, and cultural homogenization. Rafting on rivers around the country, where we expected to find classic scenes of river Americana, we found instead expensive homes, huge yachts, grassy parks, glittering conference centers, freeways, and a few abandoned riverside business districts. This inspired me to create a project that worked to preserve river culture and help build stronger river communities.

We know you must have had many magical, powerful moments on the water. What have been some of the highlights?

One of the moments that sticks with me is an evening on the Ohio River when we took the shantyboat up the Little Miami River, a tributary of the Ohio. We beached on a sandbar under an old train bridge and the setting sun transformed the sky into splashes of color from red to violet. My shipmate Age cast out a line and my partner Benzy took Hazel the dog for a walk to explore the beach. I stayed in the kitchen and made an unlikely dinner of eggplant Parmesan made in a cast iron pan on the stovetop. Later, we played cribbage and listened to the symphony of crickets. It was a lovely evening. A lot of our nights on the shantyboat are like that.

How about low moments or challenges from your river travels?

We’ve had our share of danger, from sudden storms kicked up across a long reach to a**holes in giant yachts buzzing us at speed and nearly capsizing our barge. We’ve had serious injuries from inconsiderate boaters. So we’ve come to dread those rivers in which recreational boaters are cheek to jowl, and appreciate those quiet rivers in which we have the river to ourselves.

How would you rate or describe the health or state of our rivers generally.

Prior to the Clean Water Acts of the 1970s, rivers were in a troubled state. Some polluted rivers caught fire multiple times. There were significant deoxygenated dead zones in which there were no living things in the river for miles. According to water quality experts and DNR staff we’ve interviewed, American rivers are in better shape now than they’ve been in the last 150 years thanks to the Clean Water Act. Unfortunately, there are some that would like to dismantle these regulations that saved American inland waterways.

What makes a perfect Shanty Boat? (Draft, propulsion, accommodations, etc)

The perfect shantyboat is the one that is accessible to you and feels like home… and hopefully keeps water out. I really like a barge bottom boat because of its extraordinary righting moment, low center of gravity, and high displacement and low draft. One can build the cabin that feels right for those living on it. For us, that was a gabled roof in which we tucked a double bed sleeping loft. In our 8’ x 10’ cabin, we squeezed a full kitchen, a worktable, a sizable couch, a pilot house, and a bucket toilet.

For propulsion, Shantyboat Dotty has used a 1960s 9.8hp Johnson (a little underpowered) and years later a brand new 4-stroke 30hp Mercury with power-tilt. We prefer the latter.

Why did you choose Glen-L Waterlodge plans for your boat and how was it modified or altered?

When I was casting about for plans to build my shantyboat, I wrote and received sample plans from anyone who had designed a shantyboat in the last 100 years. Most of the plans were little more than lightly annotated sketches, comparable to what you might find in a vintage Popular Mechanics article. I had already read part of Glen L. Witt’s Boatbuilding With Plywood, the bible for those building with glass and wood. It was a highly-detailed manual on tested building techniques with these two new mid-century wonder materials: plywood and fiberglass epoxy. So when I received the Waterlodge plans from Glen-L, I was pleased to find that the plans were large, extremely detailed, and quite handsome.

I built› the 20’ Waterlodge and increased the size of the cabin toward the stern by a couple feet. Naturally, no sensible plans would call for a gabled roof but that’s the direction I went. I was nervous about my modifications, so I called Glen-L to ask the experts. I reached Gayle who said, “Dunno, let’s ask the old man,” and she handed the phone to her father Glen, a legit naval architect. He approved my design with a few caveats and concerns and I hung up a little star struck. Glen must have been 95 years old at the time, three years away from his death at 98 in 2017.

Like the river itself, river knowledge is both deep and wide. In my months on the river, however, I’ve barely gotten beneath the surface of that wisdom.

What are some pieces of gear or equipment you’ve found invaluable?

People ask us occasionally what is the most important equipment we have on board. We always point to our Moka pot, the Italian stovetop espresso maker that does critically important service each morning.

We have all the usual prudent safety gear: PFDs, fire extinguishers, life ring, first aid. We have backups of many things, and tow a 16 foot Johnboat that follows behind the shantyboat like an SUV towed behind a Winnebago. That’s our go-to-town vehicle when we anchor out somewhere.

Being mostly an ocean sailor, one thing I’ve discovered I love about river travel is how the scenery and setting changes—often dramatically—with each passing mile. Rivers are often used as metaphors for life. How do you think about rivers and the course of a life, or how rivers fit with our ancestral memories and history.

Beyond the ever-changing scenery of rivers, they serve as a handy metaphor for our emotional and intellectual journeys. For me the Secret History project is both an opportunity to see the backyards of America and meet its people, and almost always an intellectual and emotional challenge that tests me and my shipmates.

One of the surprising epiphanies on the Secret History journeys is that we are all river people. The rivers that run through our towns and cities are not merely incidental aspects of local geography. Our towns and cities are located to take advantage of the river’s contribution to transportation, agriculture, and the availability of fresh water.

Like the river itself, river knowledge is both deep and wide. In my months on the river, however, I’ve barely gotten beneath the surface of that wisdom.

What can people do to lend support to your project and where should they go to see more information?

Readers are encouraged to explore the hundreds of stories, thousands of photos, and scores of videos at the Secret History of American River People website at:

https://peoplesriverhistory.us

We also share our experiences on social media. So keep your eyes open for our next fieldwork expedition in the summer of 2024 on the Atchafalaya River in Louisiana’s Mississippi River Delta. •SCA•

So wish I could find a way to have a shanty boat home in a secluded cove on Puget Sound or the San Juan Islands.

I moved to Ketchikan, Alaska in 1986 and it was home, off an on until 2006. There were quite a number of people living in "float houses", homes built on log rafts. There were even several large logging companies with whole communities of these, al interconnected with floating boardwalks. These would be towed to wherever the work was. A lot of them disappeared due to clean water regulations. In 1979 there was one in Whale Pass on Prince of Wales Island. Tthe logging company tried to get Corps of Engineers approval for septic facilities so they could build a camp on land. When they didn't get that approval they towed in the floating camp since the Coast Guard wasn't as strict about pumping effluent into the ocean (at that time).

Some of the float houses were very elaborate while others were small cabins.