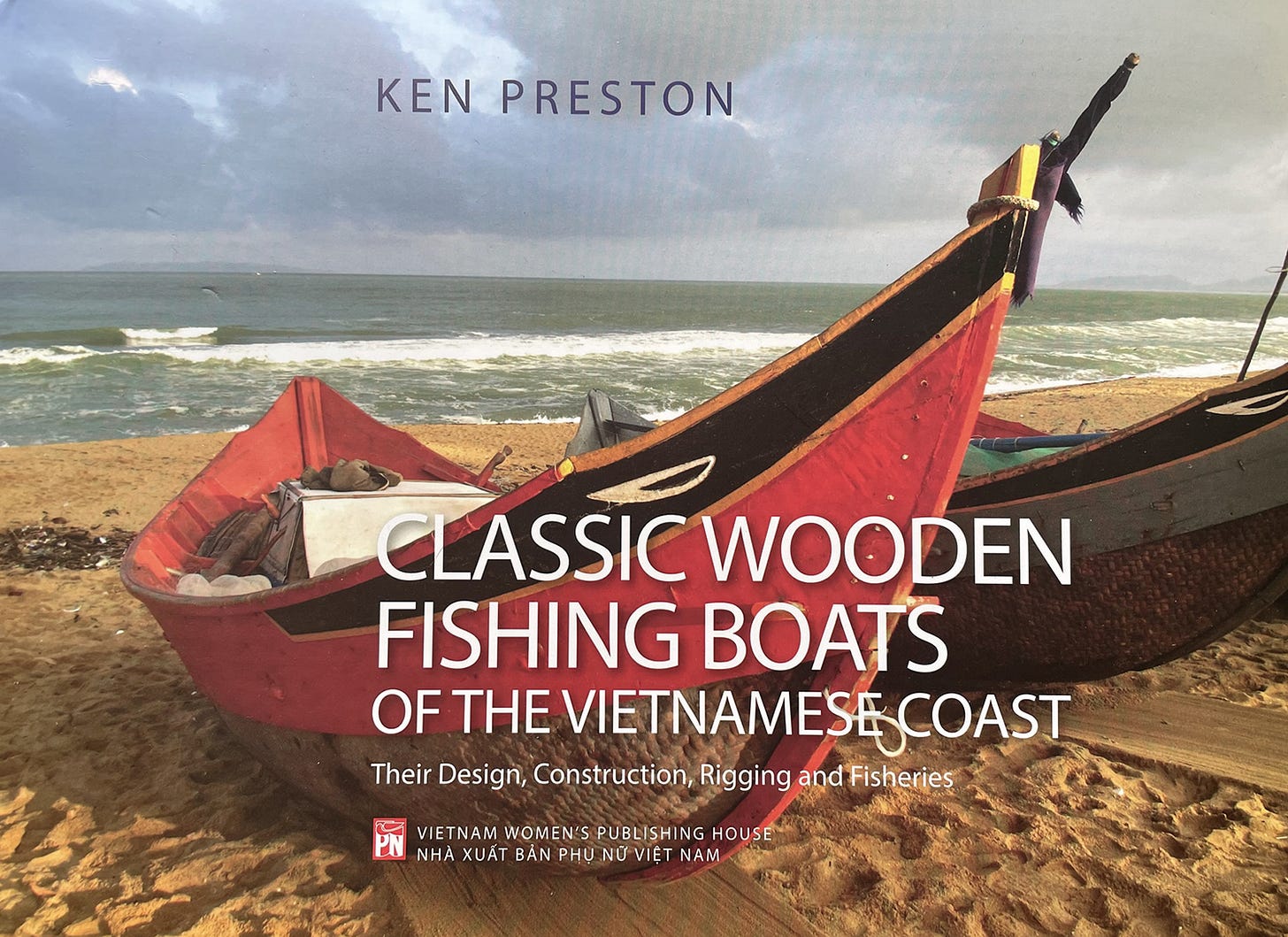

Classic Wooden Fishing Boats of the Vietnamese Coast:

The Design, Construction, Rigging and Fisheries by Ken Preston

We met Ken Preston a few years back and he told about his trips to Vietnam and his subsequent research and book. At last we are able to offer the excerpt below and a few copies for sale. We will also send one lucky reader a free copy. To enter the drawing please comment below. —Eds

The book is about the fishing boats on the Vietnamese coast in the first two decades of the twenty-first century, and very specifically, from 2005 to 2016, the period of time when the photographs and notes were all taken. It is intended to be a field guide to the boats and, to a lesser extent, to the ports and beaches they sail from, and the highway routes from one to the next. Basically, this is a photographic record, with just enough text to place the photographs in time and space and to point out their significance.

Here’s what’s in the book:

Chapter 1: Wooden Boats and Nautical Culture in Vietnam, Past and Present

Chapter 2: Vietnamese Wooden Boat Design

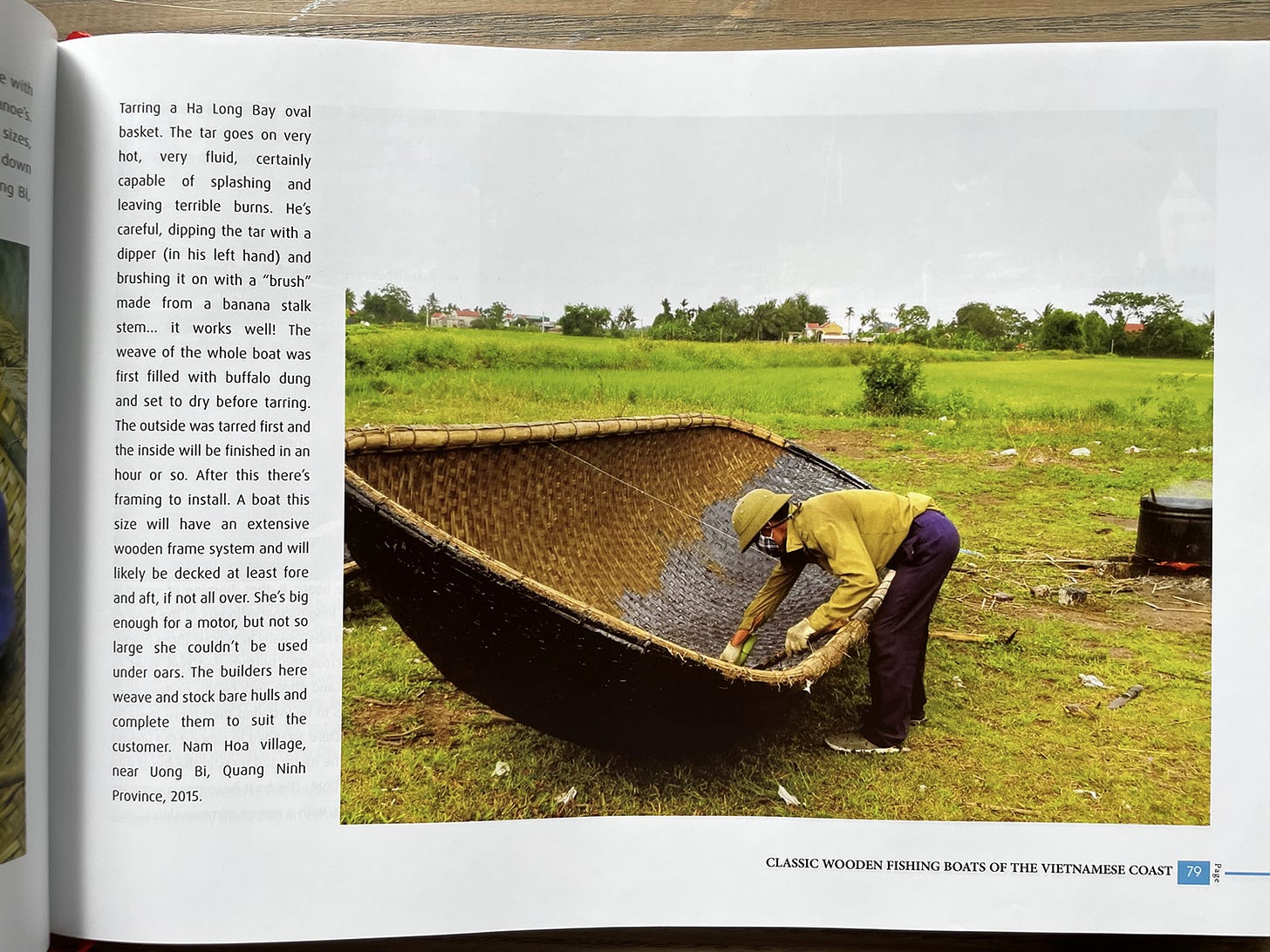

Chapter 3: Seagoing Baskets

Chapter 4: Boat Building Techniques

Chapter 5: Modern Fishing Gear on the Vietnamese Coast

Chapter 6: A Trip Up the Coast: From Phu Quoc Island to Mong Cai

Recommended Reading and Further Resources

Glossary of Nautical and Boat Building Terms

And here’s a short explanation:

I've come to write the book, or rather, to collect the photographs and write their captions, by rather a roundabout route. I began life, I think, as a boat person. I know my mother quietly disposed of at least two “canoes” I'd started building when I was still a young child, in hopes of preventing my early demise by drowning. My teen-aged winters were spent desperately waiting for the ice to go out of Alaskan lakes and rivers so I could resume my otherwise endless fishing. But I ended up in Vietnam in 1970 in the Army, not the Navy and only rarely came within sight of the sea or the Mekong River. Back from the war (alive!) I left wife and daughter ashore and went commercial fishing off the American West Coast, but it didn't take long to run through my wartime savings, with poor catches and high costs for groceries, ice and diesel fuel. By fits and starts and odd jobs I finally found my way into heavy marine construction, building docks and breakwaters and harbor improvements, never far from saltwater and boats for most of forty years. I've built or bought any number of boats over the years, mostly little things, good to paddle, row or sail around the bay, though I've been to sea on tugs and made a few small voyages sailing in Mexican and Canadian waters. In the course of my lifetime though, I've watched the American fishing fleet change radically and dwindle to a ghost of its former size and beauty. When I was a young man the West Coast harbors were filled with lovely traditional wooden fishing boats (indeed, wooden tugs still hauled barges offshore too). Now that I am old, most of those wooden boats are gone, or, at best, converted to “character yachts” or lingering in very reduced fisheries. To the extent they've been replaced, it's been with steel, aluminum or fiberglass, workable boats of course, but mostly devoid of grace and beauty, more industrial than traditional. I did see Vietnamese boats in my war time of course, beautiful bright blue sea going boats at Vung Tau for example and riverboats with big eyes near Ben Tre and Can Tho, but they slipped out of mind while I worked along and raised a family. In 2004 though, I chanced on a photo, a travel poster actually, of a palm fringed white sand beach, with a pair of beautiful bright blue fishing boats in the background. There is a little more to the story, but right then I decided to go have a look, and now, twelve years later, here's the book.

The book is divided into six main parts, with sections on boat design, building techniques, fishing gear and the like, but the bulk of the book is a more or less direct trip (and therefore an imaginary one) from Phu Quoc island (in the far Southwest of the country) to Ha Long Bay and Mong Cai, in the farthest Northeast, stopping at most of the main harbors along the way, and poking into obscure river mouths and beaches here and there as well. In reality, At the time of writing the book I'd been in the country eleven times in eleven years, for a month or two every trip and traveling five or six thousand kilometers each time. So in many cases, you'll see photographs side by side that were taken years apart but are geographically very close together. I've made a point to include the year and the location with every photo. The past twelve years have been an incredibly dynamic period of time in Southeast Asia. In decades without war, the region has seen a growing population and a booming economy. In Vietnam especially, infrastructure of all sorts, schools and universities, power plants, factories, highways, bridges, parks, airport terminals and harbors have been built all over the country. In fact there have been enormous changes in most aspects of life here. Change can be tumultuous, frightening, liberating, exciting and impossible to stop. The present can, however, be documented, so thatas it slips into the past day by day, the more interesting bits and pieces of it might be remembered. The boats in Vietnam, and the life styles of the people that make them, repair them, and take them to sea are all part of that changing and this book is intended to catch them all as they are (or have been) in this interesting bit of passing time.

The book is not a history book though, and by and large, I've made no efforts to trace the ancestry of the boats here. Other people have remarked on the similarities (and the possibilities for contact) between Vietnamese boats or boat building techniques, and the boats and ships and building methods of other times or other seafaring peoples. It isn't that those similarities and their implied connections are uninteresting, just that I'm too ignorant of the wider world or even the detailed history of these local boats to make worthwhile guesses. Now and then I can't help speculating a little, but I'll be sure you understand it's just guesswork. Mostly, there just isn't room for all the boats I wanted to show you here, so with only one exception, I've limited this book to just the boats you can see in Vietnam now, or at least that you could have seen in the past eleven years if you'd been here and went looking. I have included a short chapter at the beginning that summarizes the importance of wooden boats and sea going culture in Vietnam and the contemporary forces that are changing and threatening them.

I intended the book to be a complete accounting of the current fleet. I also thought the field work could be done in a single trip of six or eight weeks. I was wrong in both instances. It's been eleven field trips and seventy some weeks on the ground. Likewise, I'm pretty certain this is not a complete accounting; I'm sure I've missed some important boats and perhaps misunderstood others. The photographs, however, are real. They may have been cropped to cut down on extraneous sea or sky, or their color or contrast helped (dull, rainy winter days make dull, rainy photos... but they may be technically interesting and shouldn't be unnecessarily ugly), but nothing has been added or “Photo Shopped” out.

Below is a a continuing excerpt :

Wooden Boats and Coastal Fishing in Vietnam, Past and Present

Viet Nam is essentially a long sinuous coastline and two low lying river deltas, one in the north and the other in the south. Fish, from fresh water or salt, has been a major food source for the country time out of mind, with many thousands of people going to sea every day and many more working ashore to salt the fish, dry them, or carry them quickly fresh to market. Before the construction of the modern road and rail network in the early and middle twentieth century, overland transport was difficult, and shipping was by sea, in large part by sailing junks, running north and south on the alternating monsoon winds. Thus boats have been a constant necessity for the Vietnamese people, and the skilled workmen who build and repair them have been essential.

Since the 1500s at least, there has been a steady flow of international trade to and along the coast as well, sailors from India, Arabia, China and Japan, then later the English, French, Dutch and others, even Yankees from New England. Many were passing through one way or another, east or west, but many others stopped, built warehouses and seasonal homes, put their ships ashore for maintenance and repair, and stayed to do business—so the Vietnamese shipbuilders who had their own traditions and techniques dating back into pre-history, learned how other people put their ships together and could pick and choose what design details and construction techniques they might want to adopt. In more recent years, the French colonial government of the 19th and 20th century did not particularly encourage modernization of the fleet, and the natural conservatism of the sailors and shipbuilders tended to hold tight to the designs and methods that had worked for generations before.

Fortunately there are some excellent data points describing the Vietnamese coastal fleet. Besides some obscure and essentially unavailable early reports by European explorers and naval men, In 1943 (and a second edition in 1949), the French Chief of the Fisheries Department, one Jean Pietri, published a wonderful book of descriptive text and excellent pen and ink drawings of boats from the coast, starting in Cambodia and working his way around the coast all the way to southern China, one port at a time. Actual copies of his “Voiliers d'Indochine” (“Sailboats of Indochina”) can still be found in the antique book market and both an English and a Vietnamese translation are available now in facsimile paperback. The drawings and observations are superb.

Almost exactly twenty years later, in the midst of the American Vietnamese war, the US government produced two vessel identification guides for the use of the American and South Vietnamese navies. The first, The Blue Book of Junks was published to the forces in 1963 and the second, The Blue Book of Coastal Vessels, Vietnam in 1967. They are two very different volumes, but both contain an excellent selection of black and white photos and a lot of good descriptive and background text. Most important, the two American military books serve to show the rate of change in the South of Viet Nam in that era, first from the 1943 Voiliers to the 1963 Blue Book, and then from the 1963 to the 1967 Blue Book. Simply put, through all modern history to 1943, sail and oar had continued as the prime mover in the Vietnamese coastal fishing and freight fleet, presumably with designs changing only very little from decade to decade. In the next twenty years to 1963, motors arrived, especially in the farther southern portions of the coast. Though sail and oar remained very visible, radical change was afoot. By 1967, the days of Sail in what was then South Vietnam were nearly at an end. Motors by then were very common. The US government encouraged modernization of the fishing fleet to help feed the country, and Japanese motor manufacturers went so far as to provide designs to make best use of their motors.

In the North of the country during the war years and for a time thereafter the older traditions hung on and much of the fishing and coastwise freight still went under sail and oar, but by the 1990's the flood of inexpensive Chinese diesel engines and diesel fuel from Russian refineries in Viet Nam finally finished off almost all the traditional sailing fishing operations and the modern road network with its fleets of trucks put an end to most seaborne transport except for heavy bulk products like coal and limestone, moving mainly in steel hulled power barges, a lot like the barges of European rivers.

But the photographs and descriptions in the two Blue Books show a world that is gone today. In those black and white pages you mainly saw what were really motorized sail boats, more than modern fishing vessels. They were still built much as they had been for generations (though without their sailing rigs, or at best, with rigs much reduced) and, especially in the smaller sizes, the differences in designs and details from one port to the next were significant. Today the dominant larger fishing boat design everywhere in the country is a modern motor boat, owing very little to any sailing ancestors, and in general, very much the same from one port to the next. They are, however, almost entirely wooden boats still, built by hand, one at a time, and in many cases using tools and techniques that would have been familiar to boat and ship wrights in most of the world a hundred or even five hundred years ago.

But there is more change going on today. Construction of large wooden boats depends on forests of suitable trees, durable species and large sized, but such forests have nearly vanished from the region, with only remnants on the western mountainous edge of Viet Nam, and some still wild forest in the Lao mountains. Belatedly perhaps, the governments of the region have realized that at the current rate of logging soon there will be no wood for any use, and regulation and governmental control is constricting an already diminished supply. The fishing fleet of the Blue Books, traveling mainly under sail or low powered engines (and lacking refrigeration, another matter entirely), fished close to home. By and large those near-shore fish stocks are greatly reduced. Today's engine driven boats are usually larger and faster and go much farther in search of fish. The Vietnamese Government has issued regulations regarding fishing vessels today are intended to address both deforestation and the depletion of near-shore fish stocks. They restrict the construction or transfer of new boats in the smaller sizes that would be suitable for in-shore fishing, and actively encourage construction of larger distant water vessels, preferably built of steel. For now, while the fleets of smaller, traditional vessels are still sound and the supply of good timber still continues, the fishermen and the boat builders continue their work, much as they have done for untold generations, but the time is probably very near when the fish will be too scarce to chase, the hardwood logs will stop coming out of the mountains and this magnificent tradition of building and seafaring in classical wooden vessels will come to an end. Looking forward to that time, I give you this book.

Chapter Two--Vietnamese Wooden Boat Design

In 1943, Jean Pietri wrote “La jonque annamite se distingue par une caracteristique generale qui souffre peu d'exception: elle n'a pas de quille. . .” That is, “The Vietnamese junk is distinguished by one characteristic with very few exceptions: it doesn't have a keel.” He went on to elaborate that whether the boat was round bottomed or flat bottomed, the bottom was smooth, with only a couple of exceptions that were built on a rabbeted keel. Twenty years later, when the American military produced their first war time guide to Vietnamese boats, The Blue Book of Junks, that was still essentially the case, but in the past fifty years things have changed. For the sake of quick clarity in description of Vietnamese wooden boats today we can, without prejudice either way, call the smooth bottomed boats “traditional” and the boats built on a keel “western” or perhaps “modern” and we will define a “traditional” Vietnamese fishing boat in sharp contrast to a “modern motor fishing vessel” or “MFV”. I will use these terms frequently in the pages ahead, so let us settle on their meaning, at least for this discussion.

The “Traditional” Vietnamese Boat

A “Traditional” Vietnamese boat, for our purposes here, is one whose design derives more or less directly from older designs in use along the Vietnamese coast in the days before motorization, and its construction details are similarly the same as or logical extensions of construction details and techniques that were developed and refined locally over a long period of time. Such a boat will usually be relatively slender for her length and thus easily driven with the limited power available from sails and oars, especially with a small crew who are primarily interested in catching fish, not sailing or rowing for fun. A traditional boat will usually have only long, smooth, simple curves in its design, sweeping unbroken from one end to the other. Seen from above she will call to mind a canoe or kayak. The traditional boat's bow will sweep out over the sea ahead of the boat in a long easy curve, a good shape for parting the waves without slowing the boat. Quite often a traditional boat will be slender or even sharp aft, canoe-like, having regard, again, for moving easily with little power. A traditional boat will normally be built with significant flare to her sides, so she is wider at the deck than she is at the water line. Such a shape helped carry the sail in the past, and still makes a sea-kindly hull today. Since sail is essentially extinct in Viet Nam today, and diesel engines are the almost universal power, we will not require that a boat must have a sail to be traditional (though if she has one, it's likely she is!). Likewise, since essentially all the boats we will discuss are engine driven now we will allow that a “traditional” boat might have a pilot house or crew cabin on deck (something she never would have had as a sailing vessel) and still be “traditional” for this discussion.

Generations of boats like this were built and launched from this beach. Thirty years ago they still put to sea under sail, but now they are all powered with diesel engines. This one is still much the same boat though, shallow (beachable!), flat bottomed, long and slender, with her bows reaching out over the sea, slender stern where the water can see it, though she has a wide working deck added above, and a barn door rudder that is hoisted clear of the bottom as she sits on the sand. It's a drizzly morning in February, but calm. She's loaded with big bundles of drift net and the flagged buoys to mark them. She's soon off to sea. Sam Son, Thanh Hoa province, 2010…

We’re going to bring in a small batch of this book. If you’d like to order a copy you can do so here. But please allow 2-3 weeks for domestic delivery. —Eds

Great article, and I very much look forward to getting a copy of the book!

Very interesting boat designs. Would love to see them with sails.