Boat Review: Great Pelican

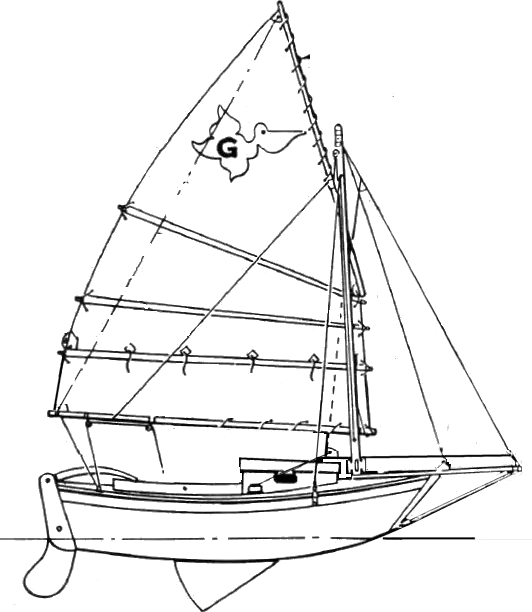

A closer look at the 16-foot Great Pelican designed by Captain William Short.

What images are evoked when you hear the term “microcruiser”? Does one of the venerable production boats like the West Wight Potter or Com-Pac 16 come to mind? Or perhaps distinctive little cruisers like Scamps or Peep Hens? Or maybe famous one-off voyagers like Manry’s Tinkerbelle or Steve Ladd’s Squeak?

While they lack a strict definition—even in sailing circles—we think of microcruisers as the smallest, lightest boats with a designated bunk or sleeping accommodations. Typically microcruisers will be a little quirky too, if for no other reason than the words “micro” and “cruiser” are eternally antagonistic—they’re always working against each other. The result is usually a boat that has a bit of a “quart in a pint pot” look to it, as it’s necessarily trying to do a lot on a short waterline. And contrary to what some might expect, quality microcruisers will rarely look like scaled-down versions of larger yachts, as the sea and designers have proven a good small boat is usually an independent creation.

One design we think fairly exemplifies the microcruiser idea (if not the ideal) is the Great Pelican. At 16 feet it’s quite small as cruising boats go, but still sleeps two comfortably with room to stow plenty of stores and gear. It’s plenty eccentric too—part sampan, part dory, and built from plywood—and like all iconic microcruisers, comes with its own attendant lore. In addition to being used to explore Baja and other remote regions, one Great Pelican owner sailed his boat from Nova Scotia to Florida, and another sailed down the West Coast to San Diego and, with novice crew, made a 32-day crossing to Hilo Hawaii (see SCA#56’s article Flight of the Pelican).

The Great Pelican is based, of course, on the original 12-foot San Francisco Pelican (see review issue #97), designed by Bill Short. Short’s many years as captain of a steam tug and sailing recreationally in the Bay Area led to his drawing his own design—one he first described as a “sailing dory-pram with lug rig.” Whatever his boxy design lacked in terms of speed and pointing ability it made up for in stability, demonstrating relative equanimity out on the Bay’s notoriously windy afternoons. As a result the original 12-foot Pelican was a big hit—around 4,000 boats have been built since its launch in 1959.

The little Pelican’s success inspired Short to draw the longer 16-foot Great Pelican, which was designed to be built with one of three different cabin configurations: standard, cuddy, or flush deck cruising model—although some were also built as open boats. With their pram bows, both Pelican models are huge for their length, but at 25% larger in length, the Great Pelican offers more than 100% additional cubic volume.

Although built in much smaller numbers than the original Pelican, Great Pelicans have proven reasonably popular. Short eventually took the concept even further, drawing an 18-foot version he called a Super Pelican and a Chinese junk version called the Yangtze 18 Pocket Junk. A stretched 14-foot version of the original 12-footer also exists, the so-called Pacific Pelican.

We were excited to finally test sail a Great Pelican ourselves, owner Doug Korlann’s well-appointed model called Toucan.

PERFORMANCE:

“Excellent light air performance, no boat in the harbor could keep up in light air. (Pointing ability) was fair in light air, not so good when the wind picked up. Reasonably fast, I never felt that she could not keep up with the crowd.” Tim Roberts, The Sarah West, 1978

“The balanced lug rig handles like a dream and is very fast off the wind. Close hauled, going without the headsail, yields the best windward performance. It really is a catboat, and the foresail is a big addition off the wind. When the wind picked up to 25 knots plus, I found running with only the headsail the easiest to handle.” Richard Sobel, GP #3

Carrying 187 square feet of sail, the Great Pelican is well-canvased, particularly if finished boats end up weighing anything like Short’s specified 480 pounds (highly unlikely we think). In any case she’s a better light air boat than you might expect, getting up to speed even in moderate winds.

Pointing ability was acceptable on our review boat—we managed to sail wherever we needed, out and down the bay and then back upwind to the dock later—but sailing close-hauled is not necessarily her strength. Where she shines is cracked off the wind some, where she can be surprisingly fast.

She seemed to go to weather best when we were heeled enough to set her hard chine, but the headsail on the Great Pelican is probably less effective than it is on most sloops, as the boat is really more like a catboat with a headsail. Even her designer considered the jib something of an afterthought. In handwritten letters to Great Pelican owner Tim Roberts, Bill Short wrote: “(the jib) is not a safety sail. It is not a ‘working sail,’ either. It is only a ‘ghoster.’… a good toy to be used in calms to be catching very light breeze.”

We found the headsail on our review boat more useful than Short’s comments would suggest (it also reduces weather helm), but the Pelican did seem to get most of its drive out of the main. With her wide cockpit and some weather helm, she kept reminding us of a traditional catboat.

Where some boats seem to slice through the water or skim across it, the Great Pelican felt like she was pushing some water—a reality confirmed in photos where you can see the wide pram plowing along somewhat bow-down. This effect was exacerbated when we had one crew sitting forward. But even though she felt a little heavy in the water and on the helm, she was still responsive and predictable, and she came through all her tacks.

TRAILERING AND LAUNCHING:

“Launching was a piece of cake, retrieval was a mess. Trying to put a flat bottom boat on a flat topped trailer when dealing with a cross current was always a challenge.” Tim Roberts, The Sarah West, 1978

“A tabernacle mast and lanyards on the shrouds made for a fairly easy set-up to launch. The bunch of running rigging strapped to the mast could be confusing enough so that someone referred to it as a spaghetti rig; the junk type mainsail needs and benefits from extra lines.” Richard Sobel, GP #3

Compared to boats her size we’d consider the Great Pelican, with its flatish bottom, retractable centerboard and kickup rudder, fairly easy to trailer, launch and retrieve. Of course with all of that interior volume it would be easy for an owner to fill the little cruiser and double or triple her empty weight.

The lugsail rig isn’t difficult to set up, but with three stays, jib sheets, a bowsprit, and optional lazyjacks, rigging can still take a while. Fortunately, the actual mast-raising is easy on those Great Pelicans with a tabernacle mast.

SEAWORTHINESS:

“The Great Pelican is very forgiving in heavy weather and inspires confidence; also, it rides dry. Initial stability and beyond is fantastic; however, it is capsizeable, non self-righting and will only heel over so far… As to weather helm; there is a fair bit, which is common with the cat rig. The barn door, ballasted, kick-up rudder with a stout tiller through the transom did well and sent the message when it was time to reef. Shortening sail was a breeze with the full batten main. The addition I made to the rig to eliminate leaving the cockpit was a ‘yard hauling parrel’ as illustrated by SV Jester, or the Hasler/McLeod rig. It tops the yard at any place on the mast, thus shaping the newly configured sail shape and area.” Richard Sobel, GP #3

“(Inspires more confidence) than her size would suggest. We never had water in the cockpit. Crossing a big wake, we might get a splash in the face, but never more than that. Our boat was built when Capt. Short did not even mention ballast. She had 20 pounds of lead in the centerboard, just enough to keep the centerboard from floating. With two people on board she was plenty stable. Later Capt. Short would recommend 500 pounds of ballast, that would have made all the difference in the world …I never felt in danger at all. We never even came close to a knockdown.” Tim Roberts, The Sarah West, 1978

“It is designed for rough waters so it does heavy weather well.” Jamyang Lodto, Sweet Pea.

To call the Great Pelican stable borders on understatement. Her nearly continuous eight-foot beam and exceptionally wide bottom provide remarkable initial stability. Nonetheless, designer Bill Short, who knew his Great Pelicans would be out braving the windy San Francisco Bay, specified additional ballast, saying, “She will be made safer with water ballast tanks low in her bilge on either side of the centerboard trunk.” Short suggested the Pelican could take as much as 500 total pounds of water in jugs as ballast. Undoubtedly homebuilders have, over the years, modified plans to suit, using different amounts and types of ballast. Our review boat, for example, was built with 100 pounds of lead in the centerboard, and owner Doug Korlann also carries a large battery and other gear down low. Owner Richard Sobel carried freshwater as ballast via 35 mylar wine bags under the floorboards.

Sailing the stable Pelican in moderate winds, it was hard to imagine ever knocking it down, but owners’ comments and anecdotes suggest that it is possible. While she has amazing initial stability and her flared dory hull provides some reserve stability, she still lacks the fixed external ballast and self-righting character of a keelboat. In fact she feels so much bigger than she actually is that it’s probably wise for sailors to remember that they’re really just sailing a big dinghy.

The Pelican’s deep cockpit (arguably deeper than it needs to be) gives crew a secure feeling and offers protection from the elements. Owners agree the boat offers a very dry ride. The accessible transom-mounted rudder and beachability add to her overall seaworthiness.

As a wooden boat the Great Pelican has some inherent flotation, but the watertight seats or other sealed areas builders install are probably a good idea. As always we suggest owners consider testing their boat’s response to an intentional capsize in a controlled environment.

During our review sail the stout Pelican inspired confidence and always felt steady as we crisscrossed the Bay.

The Great Pelican scores an excellent 158 on our SCA Seaworthiness Test.

ACCOMMODATIONS:

“The boat had a huge cockpit, bigger than my 21-footer. We usually daysailed with as many as five, four was ideal, but she was very easy to single hand too.” Tim Roberts, The Sarah West, 1978

“It worked great as a daysailer and my daughter and I even took it for an over night and slept under a boom tent while tied to a fish-buying scow in Goddard Hot Springs Bay about 15 miles south of Sitka.” Gene Buchholz, Great Pelican, open version.

Because it’s a design for the amateur builder, accommodations vary significantly from boat to boat where builders have customized as desired. But regardless of configuration, the Great Pelican will typically have some sort of V-berth with bunks for two. Our review boat’s V-berth was a generous 6' 6" long by 78"inches wide, but the berth is bisected most of its length by the centerboard trunk cap.

The volume in the Great Pelican allows for plenty of stowage options, including custom shelves, and bins beneath V-berth and cabin sole. Some builders have installed galley sinks, chart tables, and settees as well. On Korlann’s exceptionally well-appointed Toucan, original builder Lou Brochetti added what is essentially a bridgedeck, a sealed athwartships section just above seat height in the cockpit. This area is accessed as extra stowage aft in the cabin.

The cabin sides on our review boat were standard height but her builder exaggerated the crown of the cabin top to allow for proper sitting headroom (35.5 inches from berth to overhead). Headroom from cabin sole to overhead was 53 inches overall.

The Pelican’s cockpit is, as mentioned, exceptionally deep (33.5" at the stern), and exceptionally wide (83")—and this doesn’t even count the aft deck or side decks. While the deep cockpit adds security underway, it’s so deep that the skipper is compelled to stand or at least sit on a throwable cushion to see over the cabin.

The cockpit on Toucan is 22 inches shorter than plans specify, as the builder opted to increase cabin length. The resultant cockpit is still long enough (59.5") that sailing with three aboard is reasonable, but we can’t imagine 5 or 6 would be comfortable as a few owners with longer cockpits suggested.

Our review boat’s cockpit also featured some nice stowage cubbies for frequently used items.

QUALITY:

“I always felt that the boat was designed for quick and dirty home builders, we tried our best to upgrade the design wherever we could.” Tim Roberts, The Sarah West, 1978

The Great Pelican was designed for simple construction, which is great, but many builders decide to add details and flourishes that improve comfort, performance, or appearance.

The original design called for mostly 3/8" plywood construction (a 1/2-inch plywood bottom) built over a strongback and framing longitudinals—keelson, chines, and centerboard trunk. The method is well-proven on the smaller Pelican and we didn’t hear of any particular weaknesses or design flaws. Obviously quality of construction and materials varies greatly depending on the builder.

COMPROMISES:

Owners mentioned few compromises. Someone referenced the relatively small cabin and limited headroom. Another noted the fore and aft trim sensitivity, and that if someone is on the foredeck the outboard might come out of the water.

For its relatively small size, the Great Pelican is not a boat that you’d want to row any distance, meaning an outboard is more or less mandatory.

Clearly her aesthetics aren’t for everyone, but we admit to liking her chunky looks and mixed heritage character.

Finally, her speed and pointing ability were compromised some in favor of her stability, simplicity, and capacity.

MODIFICATIONS:

“Changes made to the craft after I bought it were to remove the cockpit seats with the box lockers under (rotten) and replace them with open slat seats port and starboard the length of cockpit, which opened it up considerably…The boat was bought with a fixed keel, which made the interior huge.” Jamyang Lodto, Sweet Pea.

“We did taper the mast, just for aesthetics. We raised the cabin top just high enough to install opening portholes.” Tim Roberts, The Sarah West, 1978

Again, since these boats are built by their owners, the list of modifications and derivations is long—from open versions to those with extended cabins, even one with a fixed keel instead of the centerboard.

Among many other mods that include a custom traveler and scissor mast crutch, our review boat owner, Doug Korlann, installed a luxurious Wallas ceramic stove that he uses both for cooking and heating aboard.

VALUE:

“The Great Pelican is a very roomy 16 footer with shallow draft. Various stages of ballast do not seem to have much effect on its performance. With its substantial freeboard there is a safe feeling aboard. Captain Bill Short’s Pelican idea is a winner, and quite different from the rest.” Richard Sobel, GP #3

“Now, let’s be serious here. A home-built or custom yard-built boat is going to come in considerably more than a production boat. A lot of the cost has to do with how it is finished (here I went a bit nuts with wood blocks, bronze portholes and, in the end. deadeyes). To me finish matters. Most boaters would not see the value in this but I look at boats as functional art.” Jamyang Lodto, Sweet Pea.

“I loved that boat. I have often though about building another, perhaps stretched to 20 feet. I still have the plans....” Tim Roberts, The Sarah West, 1978

Great Pelicans are rare enough birds that you’re unlikely to see one on the used market anytime soon. When they do appear it’s possible an older model might sell for $2-3k if they’re in well-used shape, or as much as $10-15k if they’re in pristine condition and feature the build quality of our review boat.

It’s an older design, but for a sailor set on building a small, seaworthy cruiser, we think the Great Pelican ought to be tempting. In addition to being a straightforward build—and one that would show progress quickly—the 16-footer lends itself to modifications and personalization and fitting more into a small space. She is, after all, a classic microcruiser. •SCA• First published in issue #104

For additional Pelican content we offer a PDF package here.

Wonderful review of a very interesting type. She's a Welsford Scamp with serious interior space.

Such a joy to see the Pelican still reviewed so highly today, 35 years after recommending the boat in our book Beachcruising and Coastal Camping.

Like you say, a classic microcruiser