Article by William Mantis

I typically spend April and May in the southern Peleponnese; more specifically in the town of Gytheio. Even more specifically, in a small house with a big courtyard, part way up the side of a mountain that overlooks the town. My grandfather bought the house in about 1925. In 1992 my wife and I assumed ownership and completely renovated the place. Though the renovation is now showing age, the cottage will still attract renters when we’re not using the place. A young couple manages the rentals. Stamos and Angeliki are both civil engineers and have two children, Grigoris and Danai. Grigoris seems to have been fascinated with boats ever since he started talking. At age, 10 he’s now old enough to join the local sailing club, which is located only a few hundred yards from a house his paternal grandfather owns.

Knowing of Grigoris’ interest in boats, I suggested to Stamos that we collaborate in building one for him. If he and Grigoris would cut the pieces over the winter, I would put them together when I get there next spring. Stamos seemed skeptical at first, but after a few weeks, expressed a willingness to at least proceed to the planning stage of the project. This was great news for me. Even if nothing ever came of it, nothing makes me happier than having an excuse to think about boats. Especially if it’s thinking about a boat I might have a chance to bring into existence and have a chance to sail. The prospect of spending some sunny spring afternoons on a daysailer, exploring the coves and caves of the Mani peninsula might give me the incentive to return to Greece until my body gives out completely. From Gytheio, it’s less than a two hour sail to some lovely destinations: beaches of all descriptions, resorts, tavernas, restaurants, a lighthouse, even a shipwreck. If you search Google Maps for “Gytheio, Greece” then scroll through the photos, you’ll be able to get a sense of what’s on offer in the area.

But back to a boat for Grigoris. My first thought was to simply reproduce my City Slicker 2.0, which I have been sailing for three seasons. She’s a fun little boat; light in weight, easy to set up and launch. Easy to build. But I quickly rejected the idea. CS 2.0 has a sail area a bit too large for a beginning sailor, given the hull’s small size, and with an overall length of 8.5 feet, the boat is a bit too small to accommodate two adults. On top of that, CS 2.0 leaves a surprisingly large wake for a boat of her petite dimensions. Whether due to her short waterline length or to too much rocker in her keel, I don’t think she will ever plane. So while a CS 2.0 might be ideal for me, a man entering his 8th decade of life, she would be far from ideal for someone in middle or high school, someone who might be interested in an occasional race, or someone who just wanted company on a sailing excursion to a nearby beach.

The second possibility was an off-the-shelf design, maybe even a kit. My online research efforts led me to a series of videos produced by a sailor/boat builder based in Portugal who has been evaluating different designs. In this video, he states that the Goat Island Skiff (GIS) meets all of his criteria, and he refers to it as “the ultimate dinghy.” The video’s producer, who calls himself “The Boat Rambler,” wants a boat that: a) is easy to build, b) is inexpensive, c) has a simple rig, d) has only one sail e) is quick to set up, f) can be launched by one person, g) is roomy enough for 3-4 people and most importantly, h) is speedy. A slow boat, in the Rambler’s estimation, is no fun to sail. The video shows his GIS sometimes reaching a speed of 16 knots, which is a rather remarkable achievement for a home-built monohull sporting an unstayed wooden mast and single low-tech lug sail; a rig that has changed little in 400 years.

So, if her 400-year-old rig does not deserve credit for the remarkable speed of the GIS, then what does? Its designer, Michael Storer, attributes it to two main factors: the hull’s light weight, the hull’s shape, and how the two factors together facilitate planing. Yet to the outside observer, the GIS hull does not differ much from other sailboats, except, perhaps, for its relatively high length to beam ratio. Her beam is 5’. Length overall is 15’ 6”. The hull, cut from 3/8” okume plywood, weighs 128 pounds, which is light but not extraordinarily so. Her bottom is a flat panel curved to create a modest amount of rocker in her keel.

Well, if the GIS is ideal for The Boat Rambler and two or three more passengers, does that necessarily mean it’s ideal for Grigoris and Stamos and, not incidentally, me? Her lug rig certainly meets the definition of “ideal,” but the hull? Probably not. First off, the GIS plans call for a lot of pieces to be laid out and cut. Since Stamos is already working 2-2½ jobs, he barely has time to spend with his family, much less finding time for a boat building project that imposes a major burden on his schedule. Secondly, a sixteen foot boat with 104 square feet of sail is too large and too over-canvased for a preadolescent sailor. In fact, both its hull and its sail area are larger than what I would choose to have in a daysailer for my own personal use. On top if that, the hull’s width is too narrow and the almost-vertical sides confer very little in the way of reserve stability. Finally, at one point, the Rambler’s video shows water pouring over the rail and into the cockpit, even at a fairly low angle of heel. Though most of the water flows back out of the boat, for me this is a deal killer. It might be okay for a boat with a self-bailing cockpit, but absent that, water in your cockpit slows you down and increases the likelihood of a capsize. For me, side decks are essential.

Well then, how about a lug rig on a hull 11’ long? Something about the size of a Moth or a Europe Dinghy, which is the one design class spin-off of the Moth. Something with side decks. By coincidence, I had been receiving information on a sailboat of that length. Named the Reverso, it’s a relatively new, very advanced product which is also capable of speeds of 16 knots. An eleven foot boat able to reach 16 knots? That’s even more surprising than the Goat Island Skiff’s capability.

No doubt, part of the Reverso’s speed is due to her very high tech sail and spars. But part of it must be due to the shape of her hull. Fortunately for the individual who is inordinately curious about hull shapes, the Reverso website provides you with a 3D interactive model. This allows you to examine it from every conceivable angle. You can download images of the hull from selected angles and render the images into two dimensional line drawings. Though the Reverso’s chines are somewhat rounded or “soft,” they’re hard enough in the 3D imaging to determine where one plane ends and another begins and to draw a line accordingly.

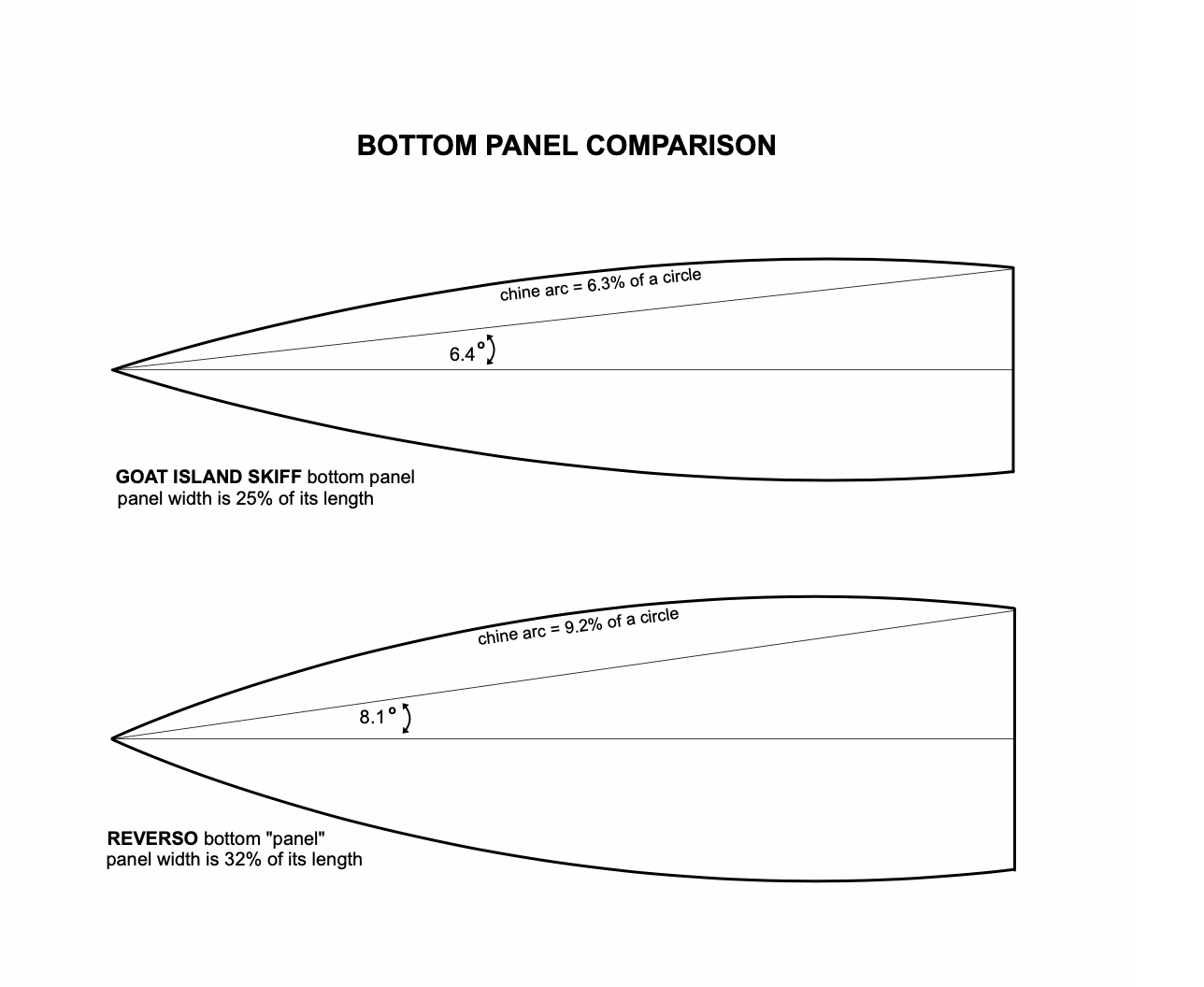

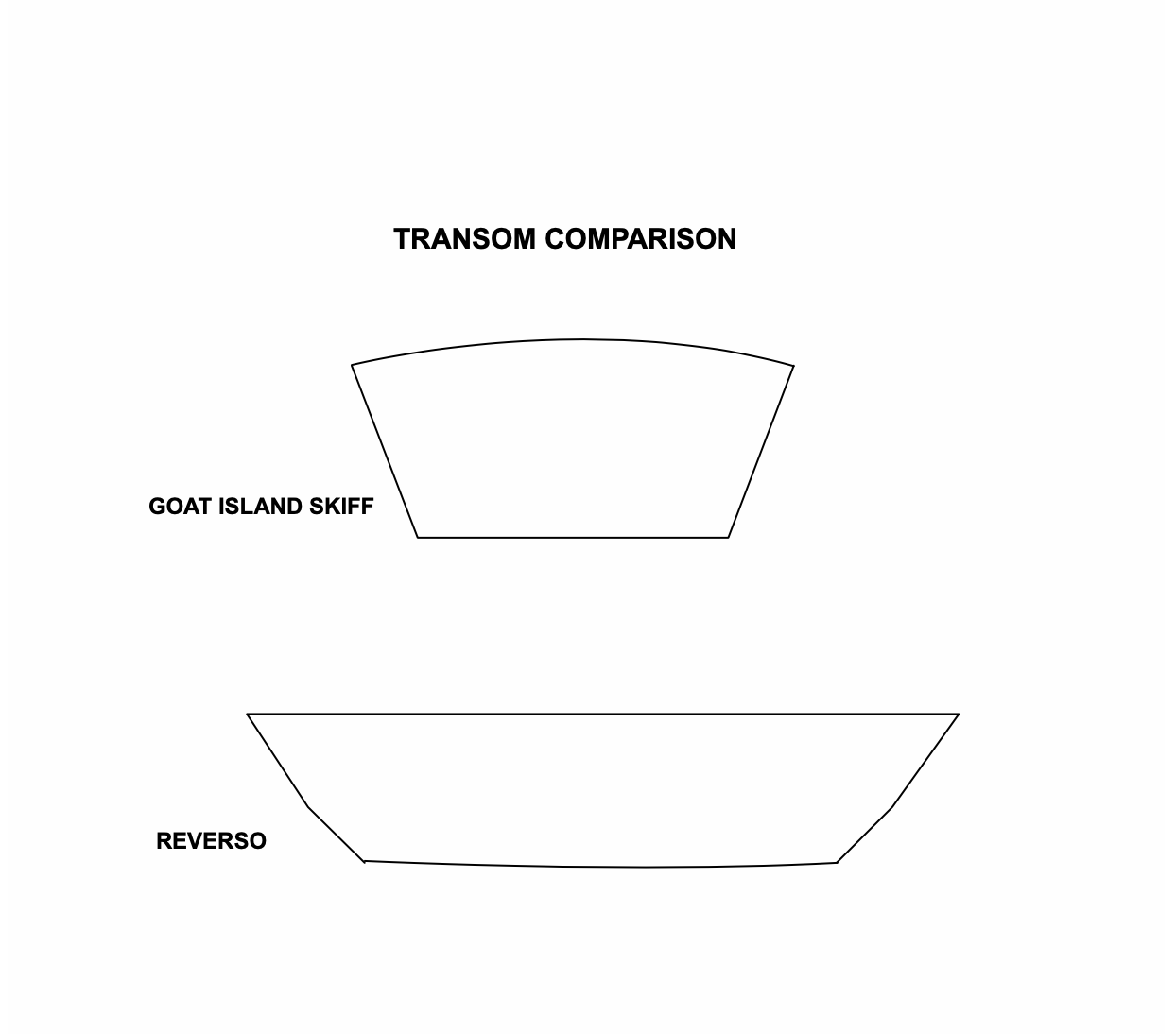

Once you have a line drawing of the Reverso hull, the similarities in the hull shapes of the Reverso and the GIS become more apparent, as well as their differences. While both hulls are reportedly quick to achieve a planing state, it’s quite apparent that they use different strategies to realize this end. Both hulls have flat bottoms with a modest amount of rocker; the Reverso with a bit less rocker than the GIS. The chines of both hulls when viewed from above describe true arcs. “True” in the sense that they represent segments of circles rather than arbitrary curves. (Side and top view comparisons.)

The two hulls differ most noticeably in their length-to-beam ratios. The bottom panel of the Goat Island Skiff bears a length to beam ratio of roughly 4:1. The Reverso has an L/B ratio of about 3:1. Interestingly, if the L/B ratio of the Reverso’s were calculated at its deck’s height, it would drop to nearly 2:1. At that height, in other words, the Reverso’s L/B ratio is similar to a traditional cat boat’s. This means the Reverso leaves a narrow footprint while her skipper has platform that allows him to hike out to keep her sailing flat and to keep her planing. It also means the hull has what’s called “reserve stability,” whereby the center of buoyancy moves further outboard as the boat heels. The Reverso acquires its reserve stability by having side panels that flare out to their gunnels. Another speed-optimizing trait that appears to be unique to the Reverso hull is a bow that rakes aft. This was done, presumably, to reduce the size and weight of the foredeck while maximizing the boat’s length at the waterline.

A simple, traditional lug rig on a hull that mimics the size and shape of a Reverso but with side decks looks like it might give us the “quick skiff” we’re seeking: quick to set up, to launch, and quick to reach its destination. The question remained, though, how quickly could a skiff of this description be built? Given what I’ve learned from my past boat-building endeavors and the arc studies I conducted to build my City Slicker 2.0, I believe the answer is pretty quick.

Incidentally, my prospective collaborators and I have not discussed a name for the future boat. I don’t even know if my opinion will be solicited on the matter. But let me point out that the name “Grigoris” and the Greek work “grigoros” share a common root. The adjective “grigoros” translated into English is “quick.” I trust that the boat’s christening will take advantage of that fact. It’s the kind of play-on-words opportunity that presents itself only rarely.

The next installment, Chapter 2, will give Stamos all the information he needs to cut the plywood panels for the hull of our unnamed skiff. •SCA•

The Boat Rambler conducted another "survey" and decided based on that to build a second boat to replace the GIS. He ended up with an OzGoose, which he seems to be having great fun with. Might be something for you to consider. Or at least taking a look at, as he did. I think his methodolgy was a bit flawed, but he seems to have abandoned the GIS in favor of the Goose.

Ask the Boat Rambler about his recent Storer Oz Goose build.