“Of all the boats you’ve reviewed, which is the best?” As the years pass and the list grows, it’s a question we often hear. Our answer is always an evasive-sounding but perfectly honest, “Depends.”

Best for an afternoon sail along a protected waterfront? Best for a week-long cruise. Best for an adventure race?

Will the boat live on a trailer or ride a mooring? How important is a shallow draft? Price? No one boat can possibly do it all, though some appear to try.

A Hobie Adventure Island trimaran is nearly perfect for close-up exploration of the Everglades, but certainly a family cruising the San Juans would be much better served by a Rhodes 22.

We love the character and capability of the Cape Dory Typhoon, but that 900-pound full keel that weighs so heavily in her seaworthiness renders her unsuitable for casual creek crawling and back-bay bashing.

Catalina’s Capri 16 might be the speediest minicruiser in her class—a force to be reckoned with on race day—but good luck overnighting in that tiny cabin on those miniscule quarterberths.

Quirky classics like the Peep Hen and Dovekie make ideal shallow-water camp cruisers, but neither would be particularly comfortable riding out rough stuff in the middle of the bay.

With the parameters more closely defined, the answer becomes easier. But even then “best” is subjective. What appeals to our aesthetics, or suits our physical characteristics or fitness level, might not work for you. And let’s not forget that sometimes the best boat is one that just feels right—regardless of her suitability. As Larry Brown says, a boat that causes you to stop and look back at her once more as you walk from the marina.

Every boat we’ve reviewed has some unique virtues and advantages—and shortcomings—although none was a total failure. True “lemons,” boats that are actually substandard because of poor design, construction, or materials, typically don’t see production in numbers that warrant our review. Sure, we’ve sailed some that had significant issues—boats that in our opinion came up short in terms of performance, seaworthiness, accommodations or trailerability, but all still offered enough to justify their existence and make their owners reasonably happy. Conversely, some have impressed us enough to stand out in our memories. Perhaps one in five has favorably surprised us and earned its way onto our list.

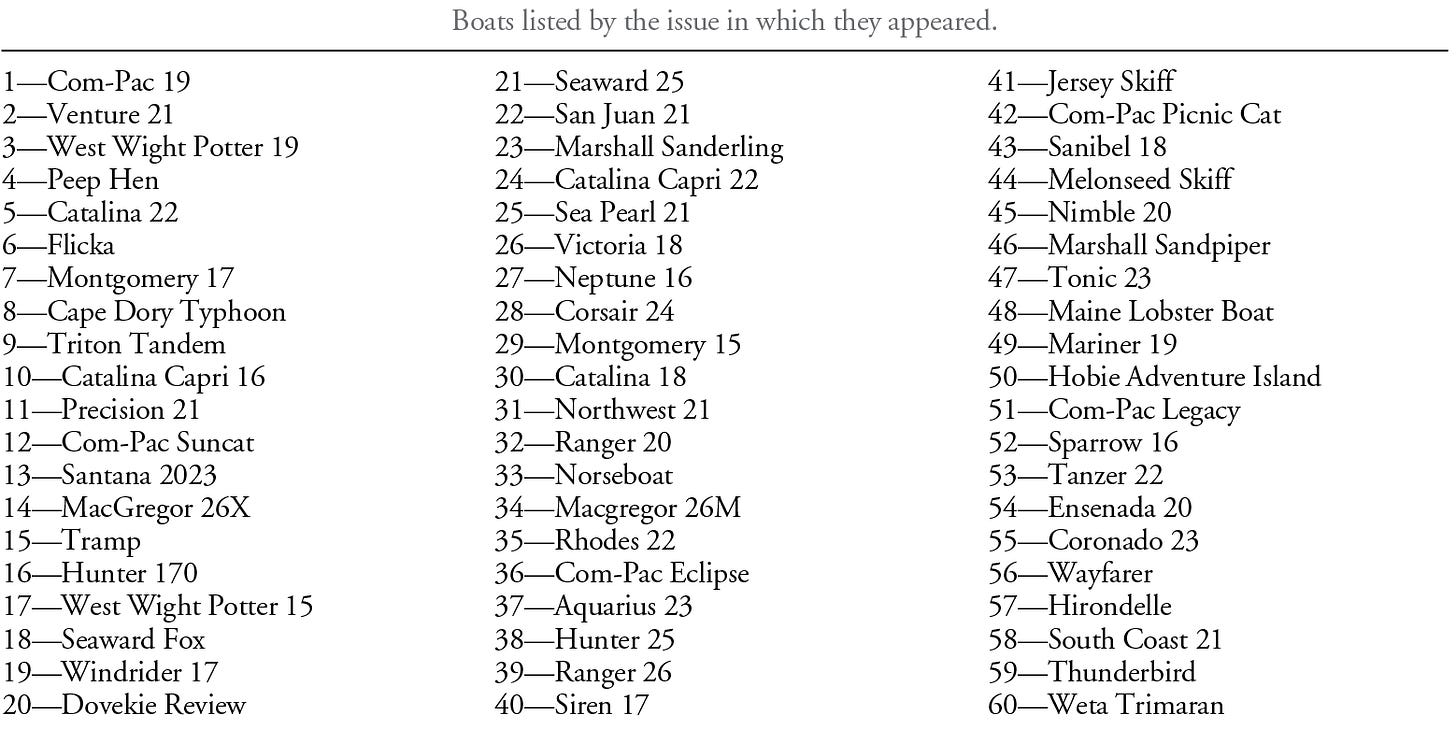

What follows, in no particular order, is a short recap of the 12 boats we found most intriguing.

RANGER 20— It’s common knowledge that scaling down a good big boat rarely results in a good smaller boat. Naval Architect Ray Richard’s Ranger 20 demonstrates that a proper small boat is an independent creation.

She’s odd looking with her broad beam culminating at knuckles along her sheerstrake, her partially decked cabin lacking windows, ports or hatches, and her Norwegian inspired ski-slope foredeck terminating over a clipper bow—but this peculiar combination produces one of the most comfortable, sensible trailerables we’ve reviewed.

The Ranger was designed with how owners actually use their boats in mind. We rarely overnight four, so bunks are limited to a generous V-berth. But because we sometimes have four or more on a daysail, the cockpit is spacious, and the open cabin means crew can escape the elements and still be part of the action.

There’s no miniature molded sink or tiny cabinets, just deep shelves and two voluminous stowage bins. The unique enclosed dodger provides a full six feet of headroom near the companionway.

With her keel/centerboard combo she’s a strong sailer—often outperforming Cal 20s and Catalina 22s. She’s self-righting with her 550 pounds of fixed ballast and, with her foam flotation, one of the largest unsinkable designs we’ve reviewed.

MONTGOMERY 15— After working alongside legendary designer Lyle Hess to create the M-17, Jerry Montgomery went to the drawing board for a slightly smaller model of his own design. With plenty of time to analyze and improve on the features of earlier microcruisers, Montgomery was able to surpass the older boats in many areas.

With her 315 pounds of shoal keel and centerboard ballast, the Montgomery 15 might be the smallest cruiser to behave more like a keelboat than a dinghy. Self-righting and solidly constructed, M-15s even have positive foam flotation. An impressive blend of seaworthiness and performance, the 15’s reputation has only been enhanced by several remarkable performances at our Cruiser Challenge, where they’ve demonstrated an uncanny ability to run away from fleets of larger trailersailers.

The 15 offers only hunched over sitting room below, but there are two comfortable bunks, a footwell for tying shoes, and a dedicated spot for a portable head.

A good case could be made the M-17 belongs on our list as well, and she’s a boat for which we have great affection, but we think pound-for-pound the 15 is superior—offering similar capability, performance and comfort at roughly half the total weight and required effort.

MAINE LOBSTER BOAT— We spend a lot of time talking about the optimum number of boats a person should own, and we’ve come to think the number is (at least!) three: Something cartoppable for maximum simplicity and ease of use, a minicruiser or mid-sized open boat for weekending, and a 19 to 26-footer for longer excursions or trips with the entire family.

But then that only addresses sailing craft. No fleet would really be complete without a rowboat and a small power skiff. In issue #48 we discovered a boat that managed to scratch three off the checklist—the Gig Harbor Maine Lobster Boat.

Based on a classic work boat, the 15-foot Lobster Boat is just light enough (375 pounds) to move fairly well under oars and—when equipped with a 10 or 15 hp motor—reach speeds of 15 mph. Rigged for sailing she makes a nimble, stable, fun family boat. And remarkably, she looks the part in each configuration.

Because of her convenient size and incredible versatility the Lobster Boat is likely to get more use than almost any boat in the fleet. Leave the outboard at home and get some exercise rowing, sail away and overnight beneath a boom tent, or fire up the outboard and do some crabbing or fishing. The ultimate in utility, it’s no wonder her kind was so popular with working mariners years ago.

HIRONDELLE— Who knew there was a flat-sailing, trailerable 2300-pound boat that could comfortably sleep a family of five, reach double-digit speeds under sail, and dare to cross oceans? We aren’t aware of any similar-sized boat that can match the Hirondelle’s unique combination of seaworthiness, accommodation and performance. How does she do all this? She’s a catamaran.

The Hirondelle offers true spaciousness below, including five useable berths, a dinette table, a functional galley, a private head, and nearly six-feet of headroom. Owners talk of dining at the salon table, surrounded by windows, sipping cocktails at sunset in a secluded anchorage—Hirondelle riding level as a waterfront restaurant. Sparkling performance and a reputation as a safe and durable sea boat make her a nearly perfect package.

Are there tradeoffs? Sure. Her fixed 10-foot beam makes trailering problematic—even requiring a special permit. Rigging and launching are also more difficult than most boats we typically review, but as a family coastal cruiser likely to be kept in the water all season, she’d be very hard to beat.

CATALINA 18— A real “sleeper,” the Catalina 18 was one of our most pleasant surprises in 60 boat reviews. Mostly lost in the shadow of he more popular siblings, the 22, 25 and 27, the 18 makes a nearly ideal mid-size trailerable. The sloop rigged, shoal keel version offers excellent performance, solid construction and exceptional seaworthiness.

Beneath her somewhat nondescript styling are some tried and true virtues. A pair of generous 1.5" scuppers, a substantial bridge deck, a toe rail, forward hatch, and positive flotation all come standard. Confirmation of her seaworthiness comes from Shane St. Clair’s account of boldly sailing a Catalina 18 from California to Hawaii—including several days of enormous seas and 40-knot winds.

Just a bit more boat than we’d want to rig for an afternoon daysail, the 18 makes an exceptionally comfortable weekender. Accommodations in both the well-thought-out cockpit and cabin are better than most boats her size, and she’ll sail with virtually anything in her class.

And buying a boat still in production has many advantages including: an active owner’s community, aftermarket parts dealers, and plenty of organized fun for those who enjoy friendly competition.

MACGREGOR 26X/M— We never cared much for the modern “speedboat” look of the big Mac. Frankly we still don’t, but it’s hard to argue with this unique boat’s success and appeal to a large number of boat buyers. Our review showed us that beauty is clearly more than gelcoat deep.

At nearly 26' and 8' of beam, the Mac is bigger than most boats that can be towed behind the family SUV—thanks to the clever use of a water ballast system that makes it not only possible but practical, while allowing relatively easy launching and retrieval. The big payoff is roomy accommodations below, true walking-around headroom, two separate staterooms, and even an enclosed head.

A decent performer in her sailboat configuration, the Mac is designed to pack as much as 60 horsepower on her transom—enough to put her up on a plane and let her cruise at more than 20 knots. Say what you want, but it enables a family to get to distant destinations quickly, and to return to port just as quickly if dangerous conditions start to threaten. Sailboat? Powerboat? Hybrid? Whatever you call her, she offers a very unusual set of virtues.

WEST WIGHT POTTER 15— This is the one that started it all, and it’s still the yardstick by which other small cruisers are inevitably measured. At 475 pounds she’s a lightweight—even among microcuisers—but the pugnacious little Potter has been involved in some very ambitious and memorable adventures over her many years. The hard-chined sloop is remarkably capable for what is essentially a 14-foot cruising dinghy, and as a last line of defense she comes equipped with positive foam flotation making her unsinkable.

With her V-berth cabin she offers everything necessary for two people to overnight (or even an extended cruise if they’re very close friends)—but not a bit more. Some of the gear that rides in the cabin by day will need to be transferred to the cockpit at bedtime, and cooking and eating are more practically done in the cockpit. Think pup tent on the water. But if simplicity as its own reward isn’t enough, there are plenty of other advantages to owning such a small cruiser. Almost everything about the Potter is simple and inexpensive. She’s easy to tow, easy to rig, easy to launch, easy to sail, and easy to maintain. There are good reasons so many Potter 15s are seen on the water everywhere small boats sail.

CRAWFORD MELONSEED SKIFF— Remember your first boat? Maybe it was a Sunfish, an Opti or a foam Snark—perhaps it was a boxy home-built scow. Whatever the boat, remember the joy when you harnessed the forces of nature and skimmed across the lake or bay toward that distant shore? It seems that all these years later many of us are still trying to recreate the magic of that first experience.

Sure, we’ve suffered from years of two-foot-itis, but now that the cost and complication of marinas, motors and mast-stepping has thoroughly inoculated us against the lure of larger boats, a Melonseed makes a lot of sense.

More sophisticated (and more expensive) than your first little boat, with plenty of teak, bronze and historical gravitas, the Melonseed manages to distill sailing to its essence. At a mere 250 pounds the sprit-rigged Skiff offers exhilarating performance—right down there at water level—and she’ll continue to sail happily along even in a minor tempest. When the wind dies, the rig stows completely inside the boat and she rows beautifully.

The Melonseed offers sailors a reminder why they fell in love with sailing in the first place. As her builder Roger Crawford likes to say, “Growing old is mandatory...growing up is optional.”

COM-PAC SUN CAT— One trick to picking the right boat—even a small one—is to avoid the temptation of going too large. We’ve long made the case that there’s a threshold of sorts at about 17 feet and 1000 to 1500 pounds. Go much beyond that and the effort required for trailering, rigging (especially mast-raising), launching and maintenance will be significant enough that the boat won’t get nearly as much use one even slightly smaller.

The 17' 4", 1500-pound Sun Cat sails right up to the hypothetical edge, offering as much comfort and capability possible without complication. The handsome Sun Cat’s single sail provides an ease of use that is further enhanced by Com-Pacs patented Mastender tabernacle system; rigging is an absolute snap.

Under-canvassed compared to many traditional catboats, the Sun Cat still manages above average all-round performance with a lighter helm. She also features our favorite keel arrangement—the keel/centerboard combo.

Her beamy hull helps provides good stability, an exceptionally spacious cockpit, and an open and airy feeling cabin with minimal accommodations.

NORSEBOAT— Just as there seemed to be a renewed interest in traditionally styled open boats, with popular new raids, rallies and traditional boat shows cropping up—along came the NorseBoat. With a topflight design team of Chuck Paine and company owner Kevin Jeffrey, and a pedigree leading all the way back to the classic Seabright skiffs, the fiberglass 17-footer is certainly one of the most exciting new production boats in the decade we’ve been publishing.

Designed as a minimalist camp cruiser, NorseBoat features an optional cockpit tent and hatch boards that fill the footwell to covert the cockpit to a double berth. Two rowing stations, impressive load carrying capacity, and positive flotation make her both versatile and safe.

Sailors who choose small open boats for cruising are a breed apart, but some evidence of the NorseBoat’s ability to cope with the rough stuff was demonstrated by her one-time record-setting performance in the rugged Everglades Challenge, and a more recent 1400-mile voyage through the Arctic.

The NorseBoat concept has proved popular enough that the company now offers a smaller 12.5-foot model, a wooden version, builder kits, and a new 21.5-footer complete with a cabin.

SPARROW 16— How we managed to overlook this little gem for so long (reviewed in issue #52) surprises us still. Looking something like a distant cousin to the West Wight Potter, the 16-foot Sparrow was designed by the venerable Ron Holder and produced in the Pacific Northwest by Northshore Marine.

Performing much better than her shoal draft would suggest, the Sparrow goes to weather reasonably well and is quick on all points. She’s exceptionally safe with 350 pounds of fixed ballast, a seat-level companionway sill, a dry-riding and self-bailing cockpit, and positive flotation.

Imagine a 900 pound boat with 4 adult-sized berths, a place for two crew to sit below in relative comfort, a built-in sink, a designated spot for the head—and no centerboard trunk intruding into the cabin. Her six-foot long cockpit is also plenty accommodating for as many as four. We’ve yet to see a boat near her size that offers equivalent cruising comforts.

Perhaps most importantly, the Sparrow is big enough to offer all of these amenities and big-boat characteristics without being difficult to trailer, rig or launch. Her mast is still one that can be raised easily with one strong arm, and in her stock configuration she’s quick to rig.

SEA PEARL 21—It seems as if every other “adventure” cruise article submission we receive features a Sea Pearl. What is it about these boats that so many people use them for cruising?

For one thing they’re marvelously easy to trailer, rig and launch. Legitimate rigging times of less than 10 minutes mean she’s a boat that will get used often. She was one of only a few designs we’ve reviewed where the trailer tires were barely wet at launch.

Loosely based on Herreshoff’s Carpenter, the Sea Pearl has a cat ketch rig and a sleek shape, making her much faster than most boats her size on most points. She’s also pretty and about as tough as a steel lifeboat. She daysails an army and converts to a utilitarian camp-cruiser for one or two under her convertible tent cabin. She’ll sail in a puddle and even rows reasonably well.

If you’re ready to take your backpacking adventures on the water, and you want to be able to explore places most cruisers can’t—it’s hard to think of a better choice than the Sea Pearl.

And if the narrow Sea Pearl is a little too tender for your tastes, she’s also offered in an ultra-stable Sea-Pearl Trimaran configuration. •SCA•

This article first appeared in issue #61.

Naturally, the WWP-15 is by far the greatest boat (Genny Sea WW)-1183). This article was fun to read and think about all the boats we have discussed over beer at some seaside bar. Oh, how I wish you were still in print. Nevertheless, this was a great read!

Owned a Com_Pac Sun Cat for 12 years, ordered it with a black hull and end boom sheeting. Changed out the rudder for a more shapely blade to improve tacking. Like Larry Brown said , I always looked back when leaving the dock, she was not only pretty but a good sailor.